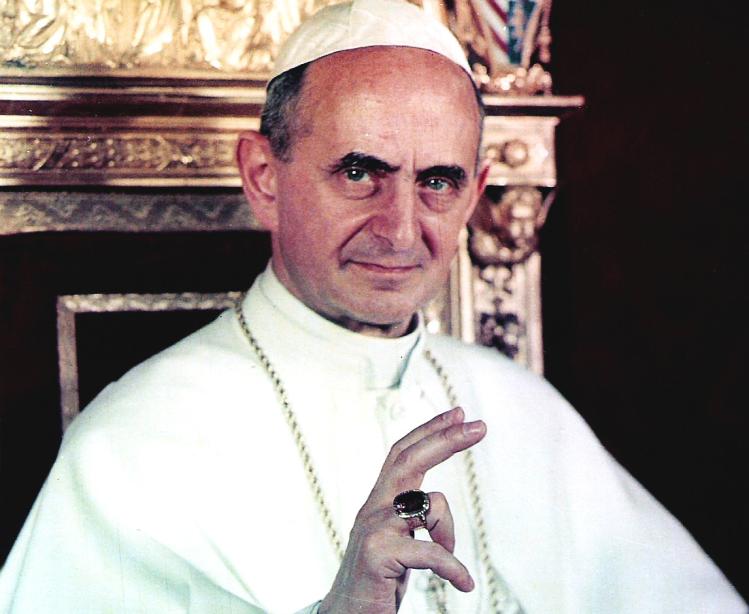

Paul VI issued Humanae vitae twenty years ago: on July 25, 1968. The anniversary is being celebrated, in some quarters, as the great dividing line between those who are faithful to the church, and those who are not. The point is well taken, but, in this case, misapplied. Faithfulness to the church—to the Gospel proclaimed and witnessed by Jesus’ disciples, and guided and enlivened by the Spirit—is essential. But faithfulness is not blind assent to assertions of authority.

Who was more faithful a century ago? Those who insisted upon the “doctrine” that the temporal power of the pope and his sovereignty over the papal states was required to assure his independence—or those who questioned it? “Temporal power” was a teaching repeated no less incessantly and vehemently—but with a good deal more bloodletting—than the ban on artificial contraception today. It, too, was invested with papal authority and became a standard of loyalty for advancement to important positions of church leadership. And it was wrong.

Twenty years ago, determination to be faithful to the church led many Catholics to conclude, and to say, that Humanae vitae was one of those tragic errors into which the church of Christ has fallen over the centuries, sometimes with the best of intentions but always with long-run damage to its mission.

A careful rereading of the encyclical, twenty years later, suggests that Paul VI, in speaking with a pastoral voice and with close attention to consequentialist arguments, may have foreseen the furor that was to come and tried to ease it; hard sayings are couched in temperate language.

Despite this, the pope’s words do not add up to a compelling, or even persuasive, argument. Indeed, in a letter that extolled the values of married love, he recognized the need for responsible parenthood, and accepted “recourse to infertile periods” (the rhythm method) as lawful, we find that the prohibition against artificial contraception, especially the pill, seems more arbitrary and ungrounded today than it did in 1968. Furthermore, for all of the pope’s insistence on natural law and the constant teaching of the church, he seems more concerned, at points, with what he saw as the dire consequences of contraception—marital infidelity, a lowering of moral standards, and the lack of incentive for the young to observe the moral law (read: fear of pregnancy).

Paul VI was right to worry, and the terrible human costs of our culture’s disarray in sexual matters is “Exhibit A” of those who currently defend the encyclical. They might be reminded of the logical fallacy of post hoc, ergo, propter hoc, but their argument is more fundamentally flawed, since the so-called sexual revolution was well under way when Humanae vitae appeared.

For all of his justifiable concern, Paul VI’s conclusions hobbled the church for the cultural struggle at hand. Responsible human sexuality means drawing lines; the sorry outcome, as we now see, was that he drew one of them in the wrong place. Rather than enhancing the church’s teaching on sexuality, the encyclical unwittingly undermined it.

The time had come to listen to mature Christians and to formulate a teaching about the truly sacramental nature of marriage and sexual intimacy, including the radical notion that sexual intercourse within marriage is a good in itself, a source of delight and comfort not only to men, but to women as well. Part and parcel of that good is the ability of married couples, and especially of women, to control the number of children they have and the spacing of births. (The continuing and unhappy consequences of Paul’s decision are painfully apparent in John Paul II’s recent encyclical, Sollicitudo rei socialis, in which there is, and can be, no serious attention to unchecked population growth as one tragic factor in underdevelopment.)

In 1968, many bishops and theologians understood that the church’s teaching had to change, that the press of the demographic revolution in both the developed and developing countries and the availability of the pill represented a turning point in the world and the church. The pope wouldn’t turn. But most married couples did, some with the support of their pastors and bishops, and some without; some with a serenity that grew from careful and conscientious thought and reflection; some with bitter and angry hearts. Other couples, far smaller in number, adopted the so-called rhythm method, some from a sense of asceticism, some in obedience to what they saw as a binding teaching. But none of these conscientious decisions resolved the dilemma in which the whole church now finds itself.

Clergy, religious, and lay teachers, caught between bishops obedient to the pope and an incredulous laity, became circumspect or fell silent on the subject of sexual morality in pulpits and classrooms. The failure to develop a fuller understanding of marriage and sexual morality has been especially detrimental to young Catholics. Where previous generations of Catholics agonized over questions of conscience, sex, contraception, and child-bearing, many younger Catholics, along with their non-Catholic peers, following the culture’s lead have adopted a contraceptive mentality and the casual sexual relations that go with it.

Some Catholics, finding the ban on artificial contraception outlandish, proceeded to question the church’s whole teaching on sexual and reproductive morality. Perhaps this is clearest in the abortion debate, where so many have succumbed to the notion that abortion is a subset of the contraception debate and judge the church’s teaching equally vulnerable. In the face of more recent developments, particularly surrogate motherhood and in vitro fertilization, a perplexed world is genuinely searching for moral yardsticks, and yet the church’s loss of credibility once again injures its efforts to speak a sane word to a potentially receptive public.

In 1968 Commonweal’s editors predicted that the encyclical “will fail the test of history.” Two decades do not make history, but so far it seems that the encyclical has failed the church.