Information transfer and skill-building can be reduced to bloodless method, and “critical thinking” is often little more than cowardly and corrosive skepticism, but education as personal formation draws on a sense of dignity and honor. “Liberal education is the counterpoison to mass culture,” Leo Strauss said in 1959, daring his listeners to stand apart. The challenging pedagogy of Plato’s Republic can’t begin before beastly Thrasymachus is humiliated, and Aristotle’s opening survey of opinions about happiness dismisses pleasure-seeking with a sneer, not an argument. Certain ideas and behaviors are beneath us. Do you have what it takes to rise above?

If the inculcation of worthy values and virtues starts by pushing against shameful ones, what happens when such acts of discrimination are stigmatized, when untrained democratic souls misinterpret the honorable service of superior judgment as the tyranny of arbitrary power? C. S. Lewis’s 1943 lectures on “the abolition of man” tease out the dangerous implications of modern philosophies—so pervasive as to infect grammar-school books—that neuter the crucial, judgment-making, spirited part of the soul, the “chest” that integrates and dignifies head and belly.

The mid-twentieth century, which experienced dehumanizing ideas and events across the globe, seems to have been especially fertile ground for reflection on the nature of education: in addition to Lewis and Strauss, this period produced now-classic reflections on education by Dorothy Sayers, Simon Weil, T. S. Eliot, Hannah Arendt, Mortimer Adler, and various “Great Books” champions. Germany had Josef Pieper, France had Jacques Maritain—and in Italy there was Luigi Giussani.

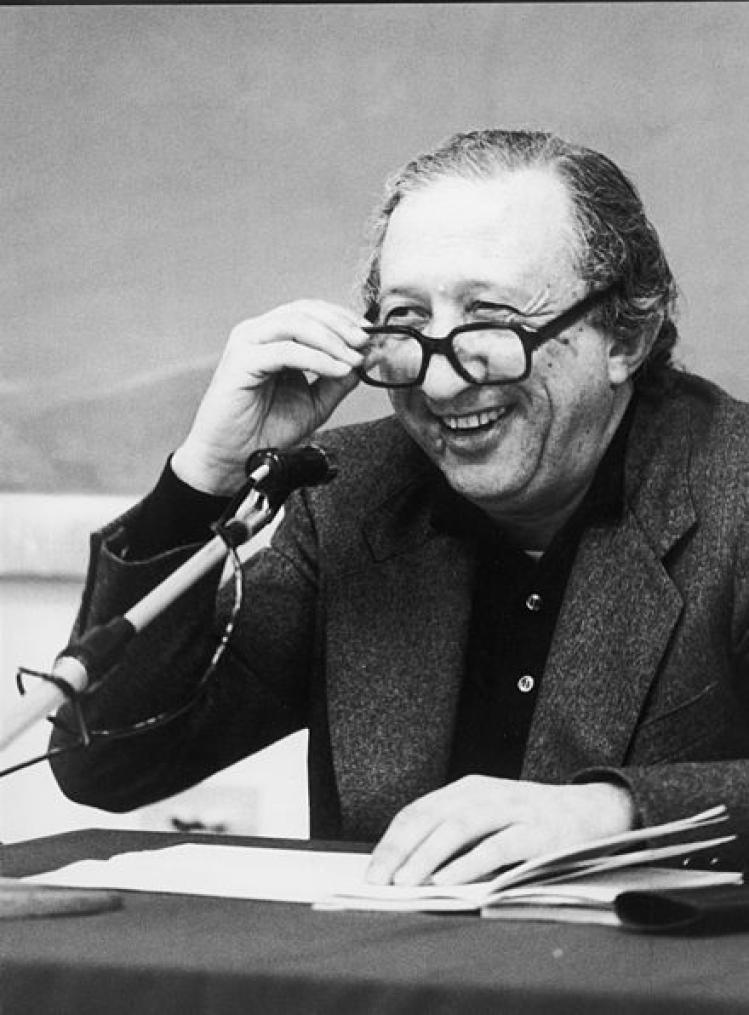

Giussani’s experience as a student and teacher made him especially attuned to the rhetorical challenge of helping young people mature in faith and reason. Born in 1922, Giussani was not yet eleven when he entered seminary. His Christian vocation was formed through his adolescence, and he continued working with youth for much of his life. Ordained a priest in 1945 at age twenty-two, he began teaching that same year in the minor seminary he had attended. In 1954, at age thirty-two, he started teaching religion at a classical high school in Milan.

During thirteen years as a high-school teacher, Giussani helped grow a youth branch of the political movement Catholic Action. He left the Milan liceo in 1967; after the political upheaval of 1968, what had been known as “Student Youth” forged an independent identity as “Comunione e Liberazione” (Communion and Liberation, or CL), now a worldwide ecclesial movement. (Giussani and his work were loved by Pope John Paul II; and upon Giussani’s death in 2005, he was eulogized by the man who, seven weeks later, would be named Pope Benedict XVI.)

Giussani had other theological works to his credit by 1977, when he published “The Risk of Education.” His reflections on the conditions of teaching adolescents had been maturing for years, his influence guaranteed an audience, and the topic, so close to his heart, made this destined to be regarded as a signature work. Still, it is hard to believe that this text, taken on its own, would otherwise have gotten much attention. It is not so much a book as a loosely structured meditation, prefaced by some autobiographical context (“Introductory Thoughts”), and with only three very lopsided chapters (the first more than twice as long as the other two combined).

Publishers don’t seem to know what to do with it. A 1995 Italian edition added an additional author’s Introduction (rebranded as a “Preface” in the new translation under review). It also appended five additional “chapters” of “Clarifications” (together not as long as the original “Chapter 1”), which were included in the previous 2001 English translation by Rosanna M. Giammanco Frongia. But these were omitted from a 2010 Italian edition, and from the current translation (which also includes no information about the history of the text). Some future critical edition will no doubt try to make sense of the various repackagings of what is, at its heart, essentially a long essay.

Giussani’s argument is straightforward. Education is an “introduction into reality,” specifically introducing the student into “total reality” or “the total meaning of reality.” This requires students to learn in and through the context of a “tradition,” which is a “hypothesis” about the total meaning of reality. Such a tradition can be presented only by authorities worthy of loyalty: persons who embody the tradition, and can therefore propose it to the student with integrity. The aim is to help young people avoid the twin errors of thoughtless conformity and irresponsible rebellion, to learn the mature perspective of appropriating and consistently applying a coherent, meaningful vision of the cosmos. To do this, students must have opportunities to engage—to test and apply in their own lives and relationships—a compellingly offered tradition. When successful, such education is friendship-making, binding student and teacher into a common experience of the world.

As with other classic proposals for education (in addition to some of those already mentioned, John Henry Newman in the nineteenth century, and Alasdair MacIntyre in the twenty-first), the specifically Christian element here is real but mostly implicit—and even philosophically contingent. The effective proposal of truths of faith presumes minds already seeking truths that are absolute, universal, and personal. Reason’s crucial combination of ambition and humility is certainly fostered by the ambiance of faith, but it is a natural human power, in principle separate from, and preliminary to, theological conviction.

What stands out to a reader of Giussani today is not so much the logic of the argument as its rhetorical mode. With keen attention to the psychology of youth, Giussani isn’t even tempted to instrumentalize education (the utilitarian trap of learning for the sake of career or power or pleasure), nor to articulate an overly intellectualist vision (seeking “truth for its own sake”). Instead he appeals directly to the restless heart, or what Sayers described as the distinguishing interest of “the poetic” stage. For Giussani, education is above all an adventure. It is this perspective that gives him the key word of his title, “risk.” Education is not safe. There are stakes—ultimate stakes: about how we should live, and for what we will die. Education implicates the “drama of freedom,” drawing out the “vital energy” of young people, for whom education is ultimately about “victory of good over evil.”

Hence the key pedagogical virtue Giussani stresses is not wisdom but courage. From the students, the requisite courage comes almost naturally; young people are constitutionally ready to venture out into the greater significance of life. Giussani quotes Seneca on “how zealous neophytes are with regard to their first impulses toward the highest ideals, provided that some one does his part in exhorting them and in kindling their ardor.”

Courage is also required on behalf of teachers, and in two ways. Teachers must have the courage of their convictions, proposing a clear tradition to their students. And teachers must push students to test that tradition, granting them freedom to do so, for only then can students actively learn to participate in and share that tradition.

Again, an emphasis on courage, critical engagement, and the testing of tradition is not unique to Giussani. What is distinctive is how he communicates these ideas with language appropriate to the argument. Giussani seeks to enact and embody the very rhetorical resources required of an effective educator: a tone that is gently encouraging, sometimes dramatic, and full of imaginative possibility.

Giussani’s rhetorical appeal seems especially suited to his original language. The cadence and tone of Italian energize even mundane expression; and the language sings not only for love and anger, but for whatever calls forth worth, pride, and nobility. This, together with the usual translation challenges, makes an English version of Giussani’s reflections almost as difficult as rendering a poem or libretto. (It also means that those influenced by Giussani and his movement can seem to speak their own language).

This new translation improves on some awkwardnesses in the older one, but elegant and natural English versions of Giussani’s voice remain elusive. Giussani describes how pressing dialectical questions can lead to an appassionata e attenta avventura di ricerca. It is technically accurate but clumsy to render this as “a passionate and careful adventure of inquiry.” (The previous translation had “a passionate and attentive quest for answers”). The sense is conveyed, but it feels like a translation. (Would it be better to take poetic liberties with a looser translation: “an intent and impassioned journey of discovery”?)

A crucial paragraph ends by saying of sound education that “it is a time that is open to invasion by the power of the eternal, and that comes to be indefatigably fertilized by it.” The older translation construes this as “a time that allows itself to be invaded by the power of eternity and to be continuously enriched by it.” One does not have to look at the Italian to sense the intention and imagine a more natural English version: “a time that submits to being pierced by the power of eternity, and is made fruitful by it.”

But there are other difficulties of translation that are harder to finesse, no matter what poetic liberties one is willing to take. The English word “meaning,” for example, just doesn’t have the weight of Giussani’s senso and significato. Or again, Giussani speaks often of valori, and uses the associated verb valorizzare. The Italian words could evoke English “valor,” but their English translations—“values” and “appreciate”—feel trite, and certainly don’t hold the tension between reason and emotion. They suggest either economic calculation, or the very emotivism Giussani’s argument is intended to avoid.

What lessons does Giussani hold for educators today? This edition includes a twenty-page foreword by Stanley Hauerwas, which turns out to be a lightly revised conference paper from 2003 (published the same year in Communio and reprinted in Hauerwas’s 2007 book The State of the University). There are obvious limitations to its use in this new edition. Hauerwas mostly quotes Giussani not from the text printed here but from the omitted 1995 appendix. Hauerwas makes an extensive comparison between Giussani and Alasdair MacIntyre, but of course without taking account of MacIntyre’s later writings on education, such as his 2009 book God, Philosophy, Universities, or his 2007 essay for this magazine, “The End of Education.” The latter argues, much like Giussani, that in a coherent curriculum, theological education helps students ask “questions with practical import for our lives,” “questions that need to be answered if we are to understand who we are here and now.” Such an education begins with familiarizing oneself with one’s tradition, in order to gain the ability to evaluate—to judge critically—the good and bad in one’s own and other traditions.

MacIntyre’s particular focus on disciplinary “fragmentation” highlights a third limitation of Hauerwas’s perspective. A foreword in 2019 could have helped readers apply Giussani’s insight to changes in education over the past fifteen years. In America these include significant developments at the primary and secondary level (the bipartisan devastation of No Child Left Behind and Common Core on the one hand, and the rise of alternative, classical, charter, and homeschools on the other). At the college level there is “the education bubble” and all of its symptoms—administrative bloat, increased economic pressure on indebted students, the quantitative and qualitative decline of the humanities, and the continued politicization of disciplines and campus culture.

Finally, touching not only all schools but all cultural phenomena, is the mobile digital revolution. Giussani describes three “conditions” for his proposed education for freedom. Students must actively engage their environment, and must experience shared community—these first two conditions are arguably intrinsic to the residential college (and further emphasized by student-affairs programming initiatives like “service learning” and “living-learning communities”). But in 2019, Giussani’s most radical proposal is his third condition: that the primary and appropriate place where students engage their own formation is in their own free time. The classical notion of leisure is alien to many young people in the age of digital distraction. Mesmerizing screens seem to make the reading and dialectical engagement of intellectual and spiritual formation “incapable of fascinating young people in their free time.” Short of banning smartphones, how can students today experience the kind of leisure Giussani imagines, and how can any creative teacher, much less an administrative initiative, foster such experiences?

Then again, Giussani’s understanding of adolescent psychology suggests that it is students themselves who will demand a return to authentic leisure, even if—perhaps because—education experts eager to expand technology access would never think to offer it. In general, the best hope for the future of education seems to be the unspoiled impulses of the young, rather than the educational theories of experts. I might not have believed it before twenty-plus years of college teaching and two of my own children’s college searches, but Giussani is right about the spiritual thirst of young people, which begins with their ability to see through ideological cant, empty slogans, and pandering clichés, and their instinctual hatred of “school” as a factory of worthless exercises.

Above all youth can smell a school’s lack of confidence the way a predator smells fear. Nobody takes seriously an invitation to a “journey” of “self-discovery” that does not boldly propose the conditions under which such a journey could be worthy and successful: “Young people feel attracted to a decisive proposal.”

At a key point, arguing that “educators must bear in mind [the] love for freedom to the point of risk,” Giussani quotes from The Hopes of Italy by the nineteenth-century statesman Cesare Balbo:

[Only] cowards want to know the statistical probability of victory on the morning of battle. The strong and the dedicated do not ordinarily ask how long or how hard, but rather how and where they must fight. All they need to know is in what place, by which way, and to what end. And then they hope, and work, and fight, and suffer there until the end of the day, leaving the accomplishments to God.

Schools offering a concrete and venerable tradition to join, and boasting honorable authorities to challenge students to join it, may not have universal popular appeal; they may even offend. But they will attract students eager to learn, and such education will only increase in value as it becomes more scarce. Any school worth surviving the education bubble must take that risk.

With Giussani’s insights into the psychology of youth, we can trust that the longing for something greater than skills, information, money, and pleasure will continue to animate Catholic education. Young people have the hunger. The best advice for educators sometimes starts with the reminder that educational expertise, like statistics on the battlefield, might do more to starve youthful vigor than to shape it. Young people will be naturally attracted to teachers and schools offering a vision of the whole. Everybody else should get out of the way.

The Risk of Education

Discovering Our Ultimate Destiny

Luigi Giussani

Translated by Mariangela Sullivan

McGill-Queen’s University Press, $17.95, 112 pp.