Whenever an event of prime human significance has transpired, stirring nations to their depths, and making a violent break with continuity, its repercussion (to use a word now pretty well naturalized in English) is to be observed, not only in literature, but in painting and the plastic arts as well. Goya’s Horrors of War, Last Judgment of Delacroix, Gericault’s terrible Raft of the Medusa, even Blake’s enigmatic cartoons, keep the turmoil of revolution for years after revolution has become history. Art works by indirection. Consequently its attacks upon what its authors conceive to be social evils escape not only the attention of the historian but the attention of those who might conceivably be interested in observing the shifts in the catastrophic public mind—the way of “looking at things” that portends changes.

It is rather surprising how little is known in this country of the group of craftsmen, artists and writers who are using their art to attack the industrial armature in England. Just before writing this article, I had the curiosity to examine the files of one of the big dailies in New York, the one perhaps which most completely and satisfactorily covers the activities of the whole world, and could find, amid its exhaustive files, but one reference to Eric Gill. The reference, it is true, was characteristic and significant. More than two years ago—in May, 1923, to be exact—a memorial to students of Leeds University, dead in the war, was to be erected. One of those happy accidents that providence knows how to arrange, put the commission for a war memorial in Gill’s hands. The result, I believe, was generally hailed by the critics who reflect enlightened judgment as artistically satisfactory. But aesthetic considerations took second place in the storm that some of the details aroused. In a frieze at the base, the daring artist had drawn a Christ, scourge in hand, before whom ran a hound with a torch in its mouth, driving the money-changers from the temple. On the base was a text from Saint James (in Latin) — “Woe to you rich men! Weep and howl for the miseries that have come upon you. Your riches are putrid.” And the money-changers wore, not the hood or mitre of Jerusalem that might have tempered the challenge, but the silk hat of stock exchanges and board meetings.

Questioned—not to say attacked—-upon the subject, Gill’s reply was rather an elucidation than a defense. “The memorial,” he told enquirers, “is a memorial to a war that has just begun—the war between stupidity and injustice. The torch symbolizes the light of reason. The Dominicans are the scientists of religion. We want today’s salvation by truth.” The dog with the torch in its mouth is, of course, the age-old symbol of the Dominican Order. Eric Gill is a member of the Third Order of the Dominicans, together with Douglas Pepler, and others of a group of laymen who have set up Saint Dominic’s Press, and live a community life that is a startling contrast to the existing social order in England. They cultivate their own land, make their own wine and beer and bread, and in their own workshops carve woodblocks, cast type, and print books, produce pictures and sculpture, with a complete disregard for all so-called labor-saving devices and complicated mechanisms, to the use of which even the most individual of artists elsewhere have so generally succumbed.

The views on social righteousness which received so dramatic a presentation in the Leeds memorial were no new things with Eric Gill, and they are shared by many thoughtful and hard-working writers and publicists in England. Gill, in fact, belongs to a group which might be called the extreme left of the Catholic economists. Chesterton and Belloc are their publicists and Father Vincent McNabb, former prior of the Dominican monastery of Haverstock Hill, in London, their theological supporter. These men see little but evil in the modern economic structure in their own country. On this they are quite convinced and are not to be shaken by the most plausible of arguments. Industrialism, for them, is of the devil—the modern big city a “den of dragons.” Imperialism—the vision that stirred Kipling to rhapsody, is a mirage that is dissolving. They are frankly “little Englanders” but with a passion of patriotism for all things English that are not too big to be loved. Society, according to them, has been bled white by poverty and the only cure is a redistribution, to be brought about by a return to mediaeval conceptions of property. Society is sick and faint, and the only thing that can rouse it from its swoon is the smell of new-turned earth, the scent of byre and sheep-fold. “Christ wept over Jerusalem,” Gill has said. “But he chose to live and work in the country.” Society is atrophied and the only thing that can restore flexibility is the play of muscles upon men who handle tools instead of levers. “The things that men have made are the best evidence. They cannot lie.” These men, it may be said, are fanatics. But they are at least honest fanatics. Not all of them are Catholics. But they turn their eyes to the Catholic Church as the one social entity not reared by human hands or committed to human compromises.

Gill’s own views on what Father Vincent McNabb in a preface terms “the asceticism of art,” are to be found in a strange little book, Songs without Clothes, written five years ago and “printed and published at Saint Dominic’s Press, Ditchling, Sussex, on the Feast of the Presentation of Our Lady A.D. MCMXXI.” The pamphlet (it is not much more) is ostensibly a “dissertation” on the Song of Songs and a defense of its legitimate place in liturgy against those who would reduce it to a mere eastern love-song, full of provocative imagery. But, in his hands, and by methods which the school of Chesterton uses very skilfully, it becomes an attack on commercialized sacred art, and a plea for a return to forms of which faith untainted by profit was the motive. “The history of art since the sixteenth century has been a faithful reflection of the progress of the world from one infidelity to another, and today we find ourselves at the nadir.” . . . “The period of decay which the renaissance ushered in ... is now past repair. We are in a sinking ship and every man must save himself. . . . The ship that brought us is on the rocks and nothing is to be saved but the toolchest and the compass.” . . . “Naturalistic painting, sculpture and music are always found concurrently with the decay of dogmatic religion. . . . Naturalism has always and everywhere been the sign of religious decay.” . . . “The Church is not the enemy of freedom. She is its only real support, and also she is the only opponent of the unjust rich. But at the present time these facts are hidden from the majority of the people by reason of the inertia and ignorance of Catholics both lay and cleric. And in nothing is this inertia and ignorance more evident than in the encouragement given to the irreligious and merely sentimental art of a commercial civilization.”

The writer was in London at the time Gill’s now famous series of the Stations of the Cross were installed in Westminster Cathedral and can well remember the storm of criticism aroused by them among traditionalists. The idea of eliminating the things to which the devout had been accustomed—the mob of priests and soldiers, the “S. P. Q. R.” banner floating overhead (very much, historically considered, as if modern soldiers were shown carrying their regimental flags to a riot call) the distant view of Jerusalem, the theatrical gestures of hatred or mourning, and of replacing them by one or two figures, symbolizing malignancy, violence or sorrow, and reduced to the barest essentials of anatomy, struck many as revolutionary. Today the stations are recognized as the most characteristic and befitting ornaments of Bentley’s great masterpiece of Christian architecture, the ones most thoroughly in key with his conception when he planned it as a monument to all time of the Church’s second spring in England.

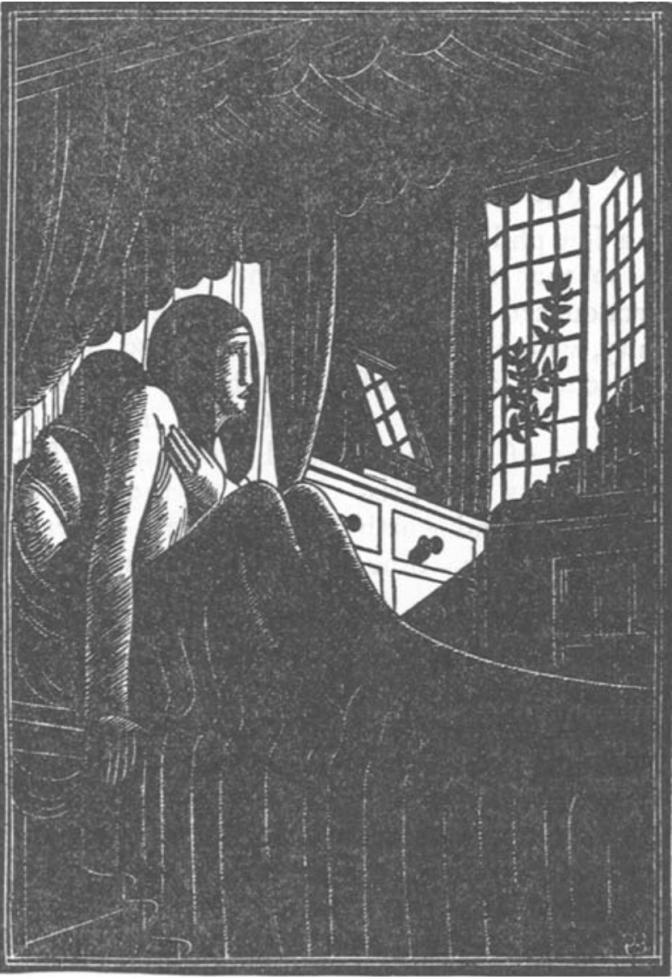

In the series of Eric Gill’s Christmas pictures with which The Commonweal decorates its Christmas number, the artist’s frugality of execution finds perhaps the theme which suits its peculiar genius best. Sophistications, even pious ones, lay down their arms before the stark accessories of the Divine birth—the manger, the ox and ass, the shepherds, the Wise Men and their camels, the star. You will notice, however, that one further step away from the “naturalism” which is Gill’s bête noir and which perhaps finds its extremest expression in Rembrandt, has been taken and that the great scene in the stable is presented in silhouette, the shadow-show at which children clap their hands. The richness that a composition can have, left dependent for its effect on the sheer rightness of the “containing” line is seized at a glance. But one can fancy that an inherent symbolism was present in the artist’s mind as he limned his picture. The other name for Christmas is Revelation. For one blinding moment in the world’s story, and one only, heaven visited earth. And the hither side of Revelation is always eclipse. Many artists of many schools have sought to convey this impression of sudden glory in their own way—by a ray of light piercing the thatched roof of the stable, by an aureole that hovers over the sacred straw. A method all the more effective for its simplicity has been chosen by Gill. Eternity’s veil is withdrawn and against its overpowering light, no detail subsists. Ox and ass, the beasts of the field, the Mother chosen among mankind, even the Child who has assumed our mortal nature show only as the shadows that heaven makes of all earthly things here below.

It is hard to study these pictures, wonderful in their quality of simple faith and child-like rapture, without a desire to know more of their author and of his work. Luckily New York has an opportunity at hand to make Gill’s acquaintance in all his picturesque phases of chap-book, social pamphlet, manual of devotion and decorative compositions. At the Chaucer Head, 32 West 47th Street, Mr. S. C. Nott, a friend of the artist, who has made the popularizing of the new movement in America his work for two years, has assembled a large collection of the products of Saint Dominic’s Press. The richness of the designs, the seemliness of type and hand-made paper are a revelation of what can be achieved by a few men who make a resolute return to old craftsmanship and hand-work, translating not only the methods but the ideals of what they conceive to be the way of economic salvation into their daily work, and proclaiming their belief that today, as six centuries ago, “by hammer and hand, all arts do stand.”

In an account of the visit to the colony at Ditchling which first aroused his enthusiasm for Gill’s work, Mr. Nott has this to say—“The printers, sculptors, artists, wood-engravers who constitute the personnel of the colony, have their workshops in low wooden buildings. Set apart from the workshops is the tiny chapel, simple and beautiful. In front, the common stretches away to the foot of the Sussex Downs where Roman earthworks can still be seen, with other mounds even older than the Romans....

“The printing press is in a large airy building, and the first thing that impresses one is the quietness, no clanging nor banging of machinery. All the presses are worked by quiet-voiced people in smocks. The peace of the eternal hills floats across the common....

“Eric Gill is one of the most interesting personalities I have ever met. He is rather strange looking, perhaps, with his long beard, untidy hair, much-worn overcoat and old grey trousers. But you cannot talk to him for five minutes without falling under his spell. He has a charm of manner that is irresistible, a keenness of humor and a merry twinkling eye. He has all the childlikeness of a true artist, the childlikeness which looks at everyone and everything without a single preconceived idea marring the contact.”