Generally speaking, you don’t go to the Frick expecting to find yourself on the cutting edge of the art world. The museum’s sumptuous collection, mounted in a Gilded Age mansion on Fifth Avenue, is opulent and monumental rather than avant-garde. Painted porcelain vases, gilded antique clocks, and sculpted fountains provide a rarefied backdrop to paintings by Old Masters hanging from wood-paneled walls. The Frick maintains strict rules in the galleries: no eating or drinking, no lecturing or loud conversations, no photography of any kind, no children under ten years old. All of this is great for preserving the art, but it can be a pain for visitors, surveilled by security and often warned not to get too close. The stuffy atmosphere tends to hinder enjoyment of the works themselves.

That’s a shame, because the Frick—temporarily housed in Marcel Breuer’s “inverted ziggurat” on Madison Avenue while the mansion is being expanded and renovated—happens to contain some of the greatest masterpieces of European painting. There’s Giovanni Bellini’s St. Francis in the Desert (1475), with its expansive, richly detailed landscape, and Johannes Vermeer’s Officer and Laughing Girl (1657), which traces the effects of light in a tight, secluded space. There are Hans Holbein the Younger’s famous portraits of Sir Thomas More (1527) and Thomas Cromwell (1532–33), Rembrandt’s wistful 1658 Self-Portrait, and paintings by El Greco, Titian, Velázquez, Van Dyck, and Goya.

What you can’t find at the Frick—or at least, what you couldn’t until now—are any paintings of (or by) Black people. Arriving almost ninety years after the museum’s inception, Barkley L. Hendricks: Portraits at the Frick, on view through January 7, 2024, is the Frick’s first-ever solo show by a Black artist. Hendricks, who died in 2017 at the age of seventy-two, was a pivotal figure in contemporary American art, his influence still palpable in the work of artists like Nick Cave, Kehinde Wiley, and Njideka Akunyili Crosby. He was also an unabashed admirer of the Frick, visiting regularly from his native Philadelphia and his studio in New London, where he taught art at Connecticut College for nearly four decades. (The catalog recounts how Hendricks often clashed with security guards who looked askance at the cameras—he called them “mechanical sketchbooks”—he wore dangling from his neck.) The show isn’t comprehensive: just fourteen portraits painted over a twenty-year period, from the sixties to the eighties, are on view. But it’s astounding, even revelatory. Hendricks’s art blends seamlessly with the Frick’s medieval, Renaissance, and Baroque collection, just as it gently critiques the exclusion of Black people and opens up new democratic possibilities for portrait painting.

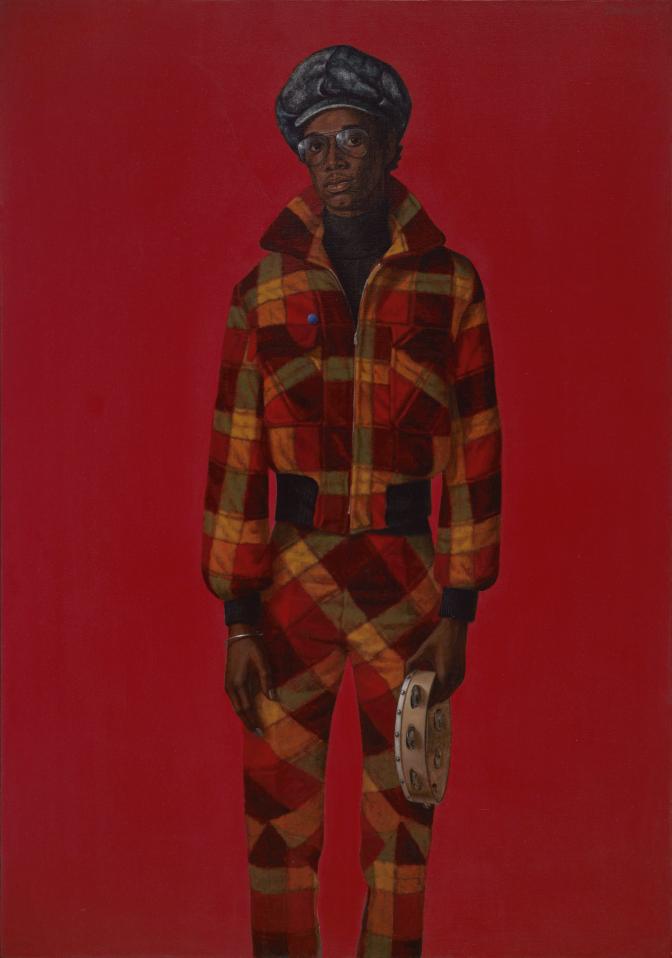

At the heart of Hendrick’s style is the idea of coolness, captured in works like Blood. Here a young Black man, cropped at the shins and standing before a matte red background, cocks his head and puffy cap slightly to the left. Everything about him—quiet eyes behind big glasses, loose slouching shoulders, slightly bent knees—is relaxed. The stillness in his stance brings out the chicness of his suit, made of orange-red flannel with a diamond pattern and a popped collar. The model was one of Hendrick’s students, Donald Formey, who, in the show’s audio guide, recalls the artist as “just the coolest guy imaginable.” With a touch of wry humor, Hendricks has also placed a tambourine in Formey’s left hand, a nod to both the trickster Harlequin from Italian commedia dell’arte (also a favorite theme of Watteau, Picasso, and Cézanne) and the simple fact that, as Formey recalls, “back then the tambourine was pretty cool on campus—whoever had one at parties was the man.”

For some, coolness implies distance and detachment, but for Hendricks, it becomes a way in, a starting point for exploring the complexity of his subjects. It can be difficult for us today to grasp just how solitary and countercultural figural painting was in the sixties, seventies, and eighties. In the United States, most of the artistic avant-garde was taken up with abstract expressionism, concerned with questions of form and individual subjectivity. In contrast, the Black Arts Movement, cofounded by poets Amiri Baraka (formerly LeRoi Jones) and Larry Neal after the assassination of Malcolm X in 1965, viewed itself as the “aesthetic and spiritual sister” of the Black Power movement and thus stood “opposed to any concept of the artist that alienates him from his community.” In other words, for Baraka and Neal, Black artists should serve the politics of liberation by depicting Black suffering.

But Hendricks had other interests. Without denying what he called “the misery of my peeps,” he looked elsewhere for inspiration and technique—specifically to Italian Renaissance artists like Piero della Francesca (1415–1492), whose paintings Hendricks had seen as a young art student in England, France, and Italy during a transformative trip in 1966. In many of Piero’s religious scenes, he pushes perspective to the limit, arranging groups of static, expressionless figures within geometrically precise architectural spaces. At first sight they can appear cold and calculated (see, for example, The Nativity or Baptism of Christ, both in the National Gallery in London). But after a time their subtle spatial harmonies—manifesting the “golden ratio” or divina proportione, as Luca Pacioli and Leonardo da Vinci called it—begin to emerge. The principle is as simple as it is provocative: the natural proportions of the human figure are mathematically consonant with the divine.

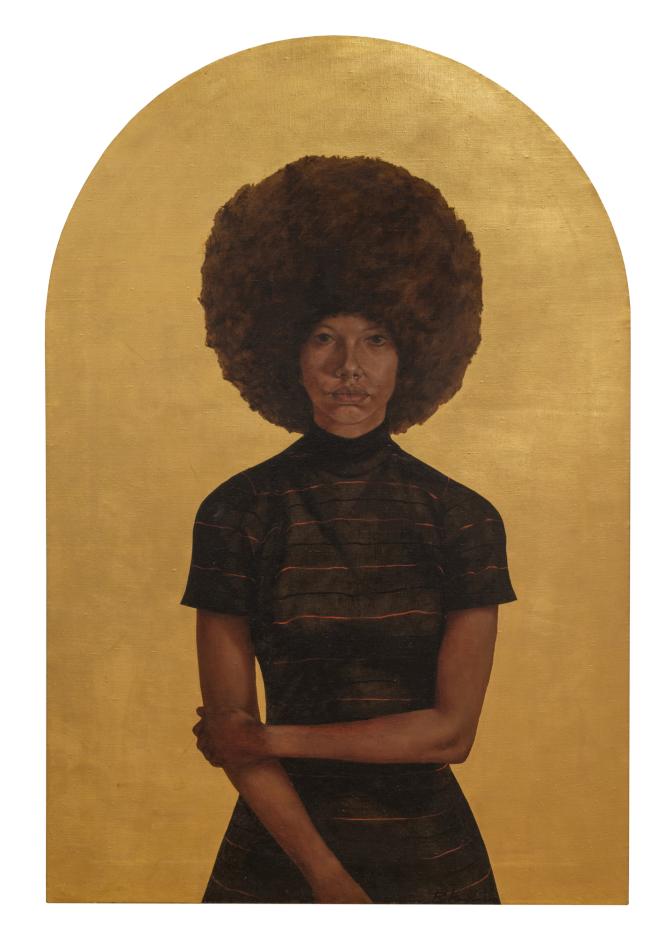

Nowhere is this more evident in Hendricks’s own work than in his 1969 portrait Lawdy Mama. One of the artist’s best-known paintings, it greets visitors as they get off the elevator on the fourth floor (curators Aimee Ng and Antwaun Sargent have slyly located it right above three of Piero’s works on the third). The work is iconic—literally so, as it’s styled after a Byzantine icon, complete with a rounded lunette top and radiant gold leaf. The subject is a beautiful young Black woman modeled after Hendricks’s relative Kathy Williams (and not, as many have supposed, activist Angela Davis). Her penetrating gaze and arched eyebrows appear beneath a massive golden-brown afro, which doubles as a traditional aureola or halo. With her exposed right elbow in her left hand, her pose evokes both shyness and strength—a fact Hendricks underscores by naming Lawdy Mama after a verse from Nina Simone’s “Blues for Mama,” which is addressed to a woman abandoned by her lover. Unfolding first as a litany of scorn (“They say you love to fuss and fight / And bring a good man down”), the song ends with Simone urging her listener to put aside her pain and reclaim her dignity: “Hey lordy, mama / What you gonna do now? / Get your nerves together, baby / And set the record straight.”

In a sense, that’s precisely what Hendricks does for his Black subjects in a series of portraits made after photographs he took on the streets of Boston, Paris, and Philadelphia in the 1970s. With their fusion of fashion, documentary photography, and pop art—Hendricks made myriad modifications to the photos in his studio—these works highlight portraiture’s paradoxical mix of reality and artifice. The subjects of Sisters (Susan and Toni) sport rings, a belt, and metal bracelets that Hendricks paints with photorealistic precision. The silver sphere earring of the woman on the left even shows a distorted reflection of the woman on the right. Similarly, in APB’S (Afro-Parisian Brothers), two thin, dapper men also appear side by side; but here Hendricks lavishes the bulk of his care on one of the men’s blue denim jeans, blending his faded pant legs with the physical threads of the canvas. (A flashy pair of overalls gets similar treatment in Misc. Tyrone [Tyrone Smith].) Hendricks’s fascination with fabric is just one aspect of his conscientious attention to the careful ways his subjects present themselves to his gaze (and, by extension, to ours).

Hendricks was equally attentive in scrutinizing himself, as in his self-portraits. These tend to be ironic and self-deprecating: in Brilliantly Endowed (not included in the Frick show), Hendricks depicts himself standing in a jaunty pose, naked except for a hat, glasses, sweatbands, shoes, and gym socks; in Slick, the artist, wearing a white suit and no shirt, stands against an all-white background in which he almost seems to disappear, his eyes half-hidden by the reflection of windows in his glasses, his hands clasped behind his back. Besides offering a sardonic commentary on his status as a Black artist, Hendricks is also asking another set of questions about the nature of painting itself: Can it really serve as a way of knowing and truly representing others? Is it fundamentally an exercise in revelation or illusion?

If Hendricks never managed to answer that question, two very different paintings in the show—one that doesn’t quite succeed and another that does—at least help us grasp how he thought about it. Ma Petite Kumquat, modeled after Hendricks’s wife Susan, is one of only a handful of portraits that Hendricks made of white people; it is also the only painting in the show featuring a subject with her eyes closed. Here, the lively, balanced poses and stylish sobriety that define many of Hendricks’s figures have been replaced by a funereal stiffness and a riot of clashing symbols. Besides the kumquat of the title, there’s a rose, a bowtie, a tasseled rope, a leopard-skin muff, and furry white leggings wrapped in gift bows. It’s a kind of anti-portrait, as if Hendricks wants to underline the radical difference between his wife Susan, a living person, and his rendering of her in a painting still as death. (It’s not surprising that after completing Ma Petite Kumquat in 1983, Hendricks didn’t paint another portrait for twenty years.)

Portraits capture a moment in time, but that doesn’t keep them from aiming at the eternal. In October’s Gone…Goodnight (a “poetic” phrase from a letter by one of Hendricks’s students), Hendricks portrays a young Black woman with short hair, glasses, gold hoop earrings, and a simple white halter dress. We see her in three different perspectives—left profile, front, and back—across a single canvas. Like Hendricks’s self-portrait Slick, October’s Gone…Goodnight is another “white-on-white” portrait that brings out the variegated tones of his subject’s skin. But it’s more visually dynamic and conceptually complex. The S-shape of the leg slit, mirrored in the subject’s bare shoulder blades, playfully adds an element of abstraction, while the model’s profile, shoulders, and back evoke the brutal iconography of incarceration and slavery. It’s as if Hendricks is tracing the whole arc of Western art history—from ancient Roman portraiture, to Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, to Peter Paul Rubens’s The Three Graces, to Andy Warhol’s factory photographs—all within a single painting that recalls the pain of Black history without letting it overwhelm the present or forestall the future.

In that sense, October’s Gone…Goodnight is, like all of Hendricks’s art, “political.” But not in the reductive, ideological way many of us (including critics and curators) have come to expect. If Hendricks’s portraits contain a “message,” it’s similar to what the fifteenth-century Italian humanist Pico della Mirandola asserted in his Oration on the Dignity of Man, a kind of manifesto of the Renaissance. In Pico’s view, human beings, despite our fragility, are worthy of reverence, “a great miracle and a wonderful creature indeed.” That’s precisely what Hendricks saw during his many visits to the Frick. It’s also what he managed to infuse into the images of the everyday people that populate his own work: “I wanted to deal with the beauty, grandeur, and style of my folks,” Hendricks said. Lucky for us, he succeeded.