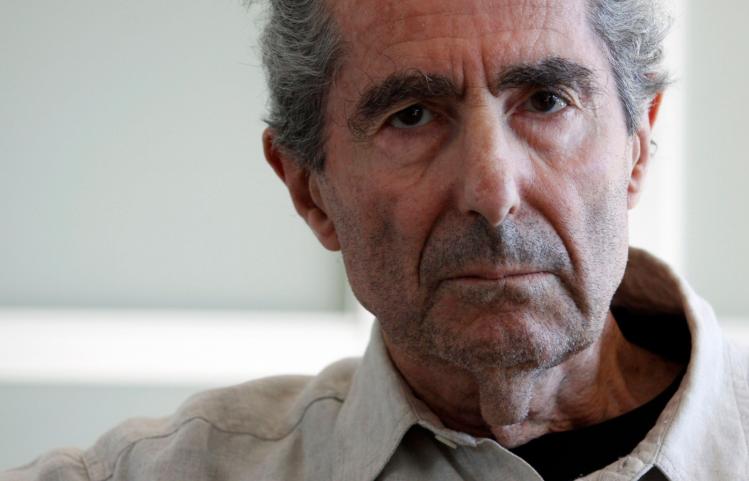

Near the beginning of Philip Roth’s 2000 novel The Human Stain, narrator Nathan Zuckerman contemplates the unlikely tattoo worn by classics professor Coleman Silk, forced out of his job on false charges of racism. The words “U.S. Navy” are “inscribed between the hooklike arms of a shadowy little anchor.... A tiny symbol, if one were needed, of all the million circumstances of the other fellow’s life, of that blizzard of details that constitute the confusion of human biography—a tiny symbol to remind me of why our understanding of people must always be at best slightly wrong.” It’s a basic reminder about human complexity but also a poke at readers and critics holding the view that Roth’s fictional narrators—from Zuckerman to Portnoy to Kepish to a meta-“Philip Roth” in 1990’s Deception—are stand-ins for the author himself, and that the public image of Roth from interviews and gossip sheets conveys his entire measure. But was anyone ever going to get Philip Roth completely right? Many thought that if someone could, it would be the esteemed literary biographer Blake Bailey, especially with the extensive and intimate access Roth granted him in the years before his death. Yet with both the highly anticipated arrival of Bailey’s Philip Roth: The Biography and what’s transpired since, it’s actually harder to know what to think—about either’s life.

By way of recap: after much advance publicity, W. W. Norton released Bailey’s Roth biography in April to great fanfare. It was the culmination of a project that began years ago, when Roth retired from writing and, after dismissing several hopefuls, anointed Bailey—the self-described “gentile from Oklahoma”—as his official biographer. The expectations, critical and commercial, were high. Bailey had already authored well-received biographies on Richard Yates and John Cheever, and now here he was with a book—the book—on Roth, one of the most towering figures in American literature after World War II. The early reviews were mostly glowing, the author interviews mostly fawning, the book itself immediately best-selling. Yes, there were some murmurs of dissent: Bailey seemed more interested in Roth’s already well-chronicled personal dramas than in his work. He seemed to be taking sides with his subject on various disputed matters and settling scores on Roth’s behalf. He seemed, even, to be in posthumous, casually misogynistic cahoots with Roth, biographer and subject figuratively yukking it up over female anatomy and tales of sexual conquest. But these were largely swept aside by the tidal wave of praise, which reached its height with Cynthia Ozick’s paean on the front page of the New York Times Book Review.

Then it all came crashing down. Bailey was accused by multiple women of grooming them when they were adolescent students of his, one also charging that years later he sexually assaulted her. Next came a rape allegation from a woman who said that Bailey attacked her at the home of a mutual acquaintance in 2015. The scandal was sudden and spiraling, and three weeks after Philip Roth: The Biography was released, Norton announced it would discontinue its printing (though the book has remained available for purchase at Amazon and elsewhere) and donate proceeds to organizations fighting sexual abuse. In May, Skyhorse Press—which has made a name for itself by taking on “canceled” books like Woody Allen’s 2020 autobiography, Apropos of Nothing—picked up the title, ensuring that it will have a paperback run. Whether people will read it is another question. Bailey is now considered toxic; the biography and Roth have suffered by association. But at least people will still have the chance to read the book if they want, and so decide for themselves what to make of things.

For many, that may depend on how kindly disposed (or not) they already are to Roth, and how much more they want to know about him. Because Bailey delivers quite a lot. He gathers and processes vast amounts of information, then assembles and arranges it for maximum narrative effect. The result is a work of scope and significance, one that happens to be highly readable over the course of its nine hundred pages—even if it now must trundle along with the freight of what its author has been accused of, and renewed attention to what its subject regularly got away with.

Bailey begins before the beginning, laying the groundwork for his examination of the writer’s life to come. A genealogy introduces us to Roth’s paternal grandparents, Galician Jews who arrived in America in the late 1800s, and his maternal grandmother, who fled the pogroms of Kiev, along with assorted other ancestors and relatives. He segues into snapshots of Roth’s 1930s and ’40s upbringing amid extended family in the Jewish ward of Newark, New Jersey—kindly neighbors, kosher meals, doting parents. His method is straightforward, his tone unsentimental. “That Roth was cherished even by the standards of Jewish boyhood is beyond doubt,” he says. “The degree to which this was a good thing is another matter.” He writes that Roth, as a teacher of literature years later, would often discuss Kafka’s Letters to His Father, about which “he once made the following note: ‘Family as the maker of character. Family as the primary shaping influence. Unending relevance as childhood.’” From 1959’s Goodbye, Columbus, and 1969’s Portnoy’s Complaint, to the work that defined his later career, that influence reveals itself with vivid insistence—even if in the psychologizing opinion of some, it might also have played a part in the real Roth’s notorious womanizing. (In time, Roth would come to describe his personal religion as “polyamorous humorist.”)

Through meticulous layering of commentary, interview, and reportage, Bailey keeps the unfolding past in constant conversation with what lies ahead, echoes sounding in all directions. The familiar stories get their biographically necessary due. Family health histories serve to foreshadow Roth’s own debilitating and sometimes nearly fatal maladies (bad back, appendicitis, heart-bypass surgery, allergic reactions to medication) later on. Formative experiences in engaging with literature at Bucknell and the University of Chicago help illustrate blooming and long-lasting intellectual relationships—friendly, fierce, and contentious—with Alfred Kazin, Bernard Malamud, Saul Bellow, Irving Howe, John Updike, and many others. American anti-Semitism announces itself to Roth via the broadcasts of Fr. Charles Coughlin (“Filthy bastard!” Philip’s father shouts at the radio one night), but for a long and painful part of his career Roth is criticized by prominent Jewish religious figures and intellectuals—“What to do with a Jew like this?” they ask, scandalized by what they discover in Goodbye, Columbus, “Defender of the Faith,” and Portnoy—while ordinary readers, including members of his family, wonder why he can’t be more like Leon Uris. Bailey is good on Roth’s small, personal kindnesses and financial generosity toward friends and on his long campaign to bring the work of dissident Eastern European authors like Milan Kundera to readers in the United States—and sometimes to bring the authors themselves. Bailey provides smaller, less familiar details, too. Four years before Nostra aetate, for instance, Roth and Kazin were featured in a symposium at Loyola University (Chicago) on the state of Jewish-Catholic relations. And long before writing God: A Biography, a former Jesuit named Jack Miles sublet Roth’s Manhattan apartment, leading to a long friendship. Miles helped Roth craft the Anne Frank sections of The Ghost Writer.

Given the volume of Roth’s output—thirty-one books of fiction—complaints about Bailey’s scanting of the work seem overblown. Might more have been better? Perhaps. But what’s here also seems like enough, and Bailey’s reading of the fiction is generally sound. (A minor but annoying exception: in summarizing the early story “The Conversion of the Jews,” which begins with two boys arguing about the virginity of Mary—“To have a baby you gotta get laid...Mary hadda get laid”—Bailey describes the exchange as a debate about the Immaculate Conception.) Throughout his career, Roth was never less than blunt about his “determination to ‘let the repellant in,’” a phrase, Bailey writes, “that would assume the force of manifesto.” You needn’t read more than a handful of Roth’s books to realize the extent of that determination. But it wasn’t gratuitous; it came tightly coupled with what James Wolcott recently called the “ruthless audit of the way Roth Man managed to intricate himself between the interlocking teeth of social-historical-psychological-sexual forces.” This is something that set him apart—significantly so—from such contemporaries as Updike.

What there is a lot of in Bailey’s book is detailed attention to Roth’s romantic and sexual relationships, beginning with his early youthful liaisons and tracking everything from the bad marriages and multiple affairs to his aggressive pursuit of much younger women late in his life. And it’s not entirely clear where Bailey stands on some of this behavior. In a podcast that aired when the biography came out, he recalled interviewing Roth: “Sometimes I’d be sitting there and he would be telling me a story and I would be thinking, ‘I can’t believe he’s telling me this.’ Because it was tasteless and unflattering to him.” In the book itself he occasionally acknowledges the problematic aspects of what he describes. But elsewhere....

I had mostly finished reading the biography before the accusations against Bailey emerged, and later, in returning to my notes, was struck by the number of passages I marked as “odd,” “creepy,” and, indeed, “tasteless.” One describes how a friend of Roth’s “played the crucial role” of helping select attractive women to enroll in Roth’s classes, performing the part of, ‘“pardon the expression, pimp’” (in the friend’s words). Well, Bailey breezily declares, “it was a different time to be sure.” Some passages feel like winks at Roth’s leering, lecherous cracks; others cruelly echo some of Roth’s own harshest criticisms of his first wife, Maggie Martinson, killed in a car wreck in 1968. A footnote identifies the biochemist whose work led to the development of Viagra, for the purpose of, well, what exactly? Mentioning “Viagra,” it seems. Later in the book Bailey appears to praise Roth’s “impulse to mock a certain kind of bourgeois piety,” calling it “among his most pronounced traits, both as a writer and a man” (strange how that “and a man” reads). But he doesn’t square this with his nodding approval of Roth’s supposed efforts to live by his favorite Flaubert dictum: “Be orderly and regular in your life like a bourgeois.” We don’t expect an authorized biographer to cast his subject in too harsh a light or challenge every inevitable contradiction. Yet there’s a feeling of complacency, if not complicity, about Bailey’s failure to interrogate more forcefully the most troubling parts of Roth’s behavior—which even in a cultural-sexual moment much different from this one drew criticism. At the time, Roth would often respond by complaining of being hauled off to “feminist prison,” and in this light, Bailey’s treatment of his calamitous marriage to and divorce from the British actress Claire Bloom comes off as an amicus brief on Roth’s behalf (which is perhaps why it’s also the least interesting part of the book).

Roth proposed the phrase “the terrible ambiguity of the ‘I’,” which he’d used in Deception, as a title for the biography. Compassion compels us to make room for ambiguities and contradictions, to refrain from judgment of what Bailey saw in Roth as “the vastly different needs of vastly different selves.” We tend to be more generous in this way with artists, particularly male artists, whom we credit with possessing creative and intellectual powers far beyond ordinary reach. But it’s easy to see how a construct like “the terrible ambiguity of the ‘I’” can also be used to rationalize any array of harmful behaviors. If there’s anything to be gained from this book’s likely inseparable linkage of author and its subject, it may be heightened alertness to the indemnifying and self-exculpatory possibilities contained within such artfully advanced propositions.

Philip Roth

The Biography

Blake Bailey

W. W. Norton

$40 | 912 pp.