Yesterday Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick signed legislation raising the state’s minimum wage from $8.00/hour to $11.00/hour, by Janury 1, 2017. That’s the highest statewide minimum wage in the country. It means full-time minimum wage workers in the Bay State can look forward to an additional $6,000 in annual income.

Boston magazine’s David Bernstein, one of the savviest political reporters in the commonwealth, noted earlier today that the minimum wage increase is further proof that Massachusetts has entered “a new Golden Age of Law-Making By Threat of Popular Vote”, adding “I’m not sure whether that’s a good or a bad thing, but it’s definitely a thing.”

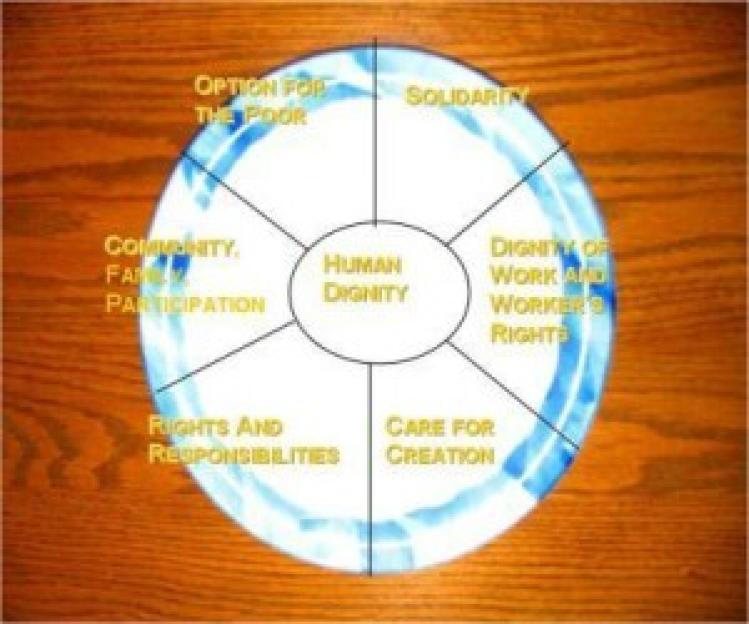

It’s also a sign of the Catholic Church wielding political power in a different way than it sometimes has in the past. At the heart of the Raise Up Massachusetts coalition that gathered over 350,000 signatures to put initiatives to raise the Minimum Wage, and to create an Earned Sick Time benefit for all Massachusetts workers, before the legislature and the electorate are several faith-based community organizations affiliated with the Massachusetts Community Action Network. Other faith-based community organizations (including the Merrimack Valley Project where---full disclosure---I do some work) also participated in the campaign.

In addition to a shared approach to organizing, these organizations---along with others like the Greater Boston Interfaith Organization (about which, more shortly)---have all been seeded with funding from the Catholic Campaign for Human Development. CCHD isn’t the only, or even the majority funder, of these organizations; but for over four decades CCHD has been perhaps the steadiest source of funding for organizations that seek to engage poor, working-class and middle-class people to act collectively on their shared values and interests. That’s true not just in Massachusetts, but in all 50 states across the country.

It’s to an earlier campaign that Bernstein traces the origins of Massachusetts’ current political age:

“The era properly dates to 2006, when a coalition of groups wanted to hold political feet to the fire (specifically, the tootsies of Governor Mitt Romney, Senate President Robert Travaglini, and House Speaker Salvatore DiMasi) on their promise to enact health care reform to cover the uninsured. They pushed forward with a universal health care initiative that was polling at one point at 66 percent in favor. The broad nature of the ballot measure, to put it bluntly, scared the piss out of insurance companies, health care providers, and business owners. For a long time, those folks thought they could get the do-gooders to back down, but they held firm and kept moving forward with the initiative process, and eventually the stakeholders worked out the law the country now calls RomneyCare.”

GBIO was at the center of that coalition. In addition to gathering signatures to make real the threat of health care reform by referendum, GBIO leaders “consistently and persistently” (in the words of then-lead organizer Cheri Andes) turned out hundreds and thousands of ordinary citizens for legislative hearings, rallies and other events in the months and years leading up to the passage of RomneyCare. In the years since, GBIO has continued to push other stakeholders in Massachsuetts’ powerful health care industry to make health care more affordable.

To say that that all this represents a shift to a “bottom-up” political strategy in the Bay State by the Catholic Church would be going too far. The Massachusetts Catholic Conference, statewide public policy arm of the state’s four dioceses, prominently and repeatedly endorsed raising the minimum wage, for example. Also, there are important public issues---like a narrowly defeated “death with dignity” referendum in 2012---that these faith-based community organizations do not address. (The bishops and the MCC played a critically important and---as has become customary since Cardinal Sean O’Malley’s arrival---carefully nuanced role in that campaign.)

Cardinal O’Malley and his brother bishops across the state continue to speak out on a range of public issues when and as they see fit. And Roman Catholics continue to be well represented in political and economic seats of power across the commonwealth. Nonetheless, the growth of broad-based community organizations that bring Catholic parish leaders together with local leaders of other denomination and religions, as well as labor unions and other community groups is a trend worth noting.

With the making of public policy largely ground to a halt on the federal level, the next several years may be a time of increased political change on the local, state and regional level. That shift in turn may mean increased opportunities for faith-based community organizations to act powerfully on their values and in the interests of their members...and the wider society.