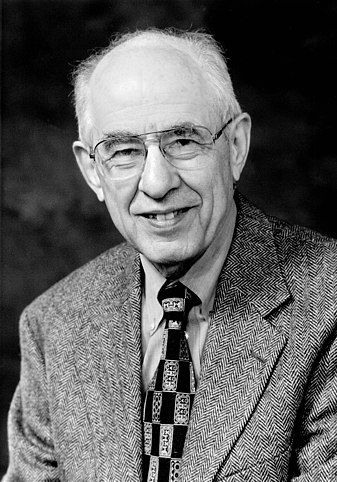

The philosopher Hilary Putnam, who taught for decades at Harvard University and wrote brilliantly across nearly all areas of philosophy, died on Sunday evening. I am indebted personally to Putnam—he was the doctoral supervisor of my own doctoral supervisor, and also of another of my most influential teachers—but would not know where even to begin in summarizing the importance of his life and work. Thanfully Martha Nussbaum, for many years Putnam’s colleague at Harvard, has written an essay in which she does just that. Here are a few key paragraphs:

The philosopher Hilary Putnam, who taught for decades at Harvard University and wrote brilliantly across nearly all areas of philosophy, died on Sunday evening. I am indebted personally to Putnam—he was the doctoral supervisor of my own doctoral supervisor, and also of another of my most influential teachers—but would not know where even to begin in summarizing the importance of his life and work. Thanfully Martha Nussbaum, for many years Putnam’s colleague at Harvard, has written an essay in which she does just that. Here are a few key paragraphs:

Those of us who had the good fortune to know Putnam as mentees, colleagues, and friends remember his life with profound gratitude and love, since Hilary was not only a great philosopher, but also a human being of extraordinary generosity, who really wanted people to be themselves, not his acolytes. But it’s also good, in the midst of grief, to reflect about Hilary’s career, and what it shows us about what philosophy is and what it can offer humanity. For Hilary was a person of unsurpassed brilliance, but he also believed that philosophy was not just for the rarely gifted individual. Like two of his favorites, Socrates and John Dewey (and, I’d add, like those American founders), he thought that philosophy was for all human beings, a wake-up call to the humanity in us all.

Putnam was a philosopher of amazing breadth. As he himself wrote, “Any philosophy that can be put in a nutshell belongs in one.” And in his prolific career Putnam, accordingly, elaborated detailed and creative accounts of central issues in an extremely wide range of areas in philosophy. Indeed there is no philosopher since Aristotle who has made creative and foundational contributions in all the following areas: logic, philosophy of mathematics, philosophy of science, metaphysics, philosophy of mind, ethics, political thought, philosophy of economics, philosophy of literature.

And Putnam added at least two areas to the list that Aristotle didn’t work in, namely, philosophy of language and philosophy of religion. (Philosophy of religion because he was a religious Jew, and he understood Judaism to require a life of perpetual critique.) In all of these areas, too, he shared with Aristotle a deep concern: that the messy matter of human life should not be distorted to fit the demands of an excessively simple theory, that what Putnam called “the whole hurly-burly of human actions” should be the context within which philosophical theory does its work.

Nussbaum goes on to talk about Putnam’s remarkable tendency to change his views and argue against his previous ones. (A joke among philosophers is to ask “Which Putnam?” in response to a description of his views. Indeed, the Philosophical Lexicon, a philosophers’ jokebook of pseudo-technical terms, defines ‘hilary’ as “A very brief but significant period in the intellectual career of a distinguished philosopher.” As in -- “Oh, that’s what I thought three or four hilaries ago.”)

She concludes:

A life in reason was and is difficult. All of us, whether we are ignorant of philosophy or professors of philosophy, find it easier to follow dogma than to think. What Hilary Putnam’s life offers our troubled nation is, I think, a noble paradigm of a perpetual willingness to subject oneself to reason’s critique. Our country, founded by lovers of argument, has become the plaything of rhetoricians and entertainers (characters that Plato knew all too well). On this day when we have lost one of the giants of our nation, let’s think about that.

I only wish that I could do better than quote. The entire essay is worth reading.