The fifty-fifth story in Joy Williams’s Ninety-Nine Stories of God reads as follows:

55.

The Lord was asked if He believed in reincarnation.

I do, He said. It explains so much.

What does it explain, Sir? someone asked.

On your last Fourth of July festivities, I was invited to observe an annual hot-dog-eating contest, the Lord said, and it was the stupidest thing I’ve ever witnessed.

NEGLECT

The Lord of this story isn’t the Lord we’re used to hearing about. He isn’t omniscient or omnipotent. He doesn’t appear to be the source of judgment or mercy. Rather, he is much like us: grasping at whatever explanation might best account for his experience of the world (here, reincarnation); bemused and disgusted, puzzled and wearied, in the face of human absurdity.

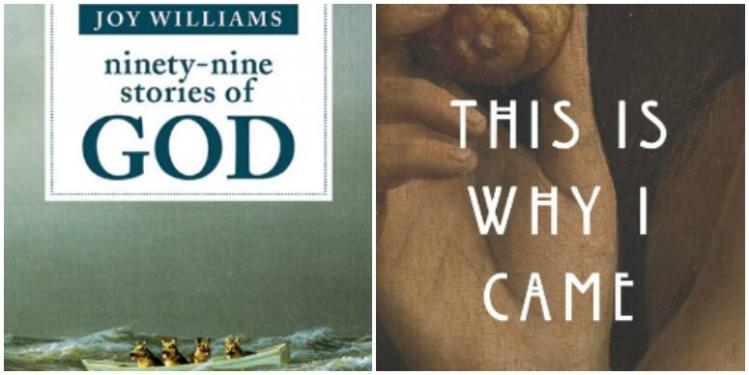

Williams is a brilliant novelist and an even more brilliant short-story writer, a precise but unfussy stylist with a true visionary’s sensibility. Ninety-Nine Stories of God (Tin House Books, $19.95) is something of a departure from her previous work. The structure of the above story—a bold-type number, followed by the short story itself (some even shorter, even just a single sentence), followed by a capitalized gloss of the story at the end—repeats itself throughout the book. This is flash fiction at its flashiest: the stories are radically condensed, often koan- or parable-like in their brevity, containing the merest scrim of a narrative and asking the reader to do much of the interpretive work.

In this story, we might laugh at humanity’s unrefined appetites, but this laugh quickly gives way to questioning. How does reincarnation offer the Lord an explanation of a world that contains such a contest? (Maybe because a species that would indulge in such a stupid act deserves to find itself, in the future, inhabiting a lower life form.) Who has neglected whom—or what—in this story? Has the Lord neglected his creation in allowing such gluttony? Has humanity neglected reason? Has America neglected its ideals, celebrating political independence by consuming absurd amounts of processed meat? Finally, why end the story with the word “witnessed”? In what sense is the Lord a witness to creation? Is he a prophetic witness, criticizing humanity’s stupidity? Or is he a witness to a crime, unable to do anything but say yes, this contest, hard as it is to believe, has in fact taken place?

IN THIS AND in many of the book’s other stories, the Lord stands at a distance from the world, baffled by humanity and its actions. Williams’s God is often an absentee God:

The Lord was invited to a gala. Beautiful women, beautiful men, beautiful flowers. Astonishing music from that moment’s finest string quartet. All that was served was champagne and mountains of Kamchatka caviar.

The hosts were somewhat nervous about the Lord’s reaction to the caviar.

After all, the lives of many thousands of female wild salmon were sacrificed for their eggs, and the renewable potential of their offspring lost forever.

But the Lord never showed up.

PARTY

As with the hot-dog-eating contest, the Lord here seems horrified by humanity’s casual, cruel wastefulness, especially its willingness to destroy the natural and animal world to celebrate itself or its gods.

In both her fiction and her nonfiction, Williams has written about our inability—rather, our unwillingness—to see the world as gift and grace. As she put it in Ill Nature: Rants and Reflections on Humanity and Other Animals, “Your fundamental attitudes toward the earth have become twisted. You have made only brute contact with Nature; you cannot comprehend its grace.” Throughout Ninety-Nine Stories of God, we see this twisted attitude playing out, and we see that this playing out alienates God from humanity. A later story begins like this: “The Lord was living with a great colony of bats in a cave. Two boys with BB guns found the cave and killed many of the bats outright, leaving many more to die of their injuries. The boys didn’t see the Lord. He didn’t make His presence known to them.” When the boys implore the Lord to “hang more in the world of men,” he refuses: “the Lord said He was lonely there.” Another story ends with this exchange between the Lord and a pack of wolves that are being hunted down and killed:

Sentiment is very much against us down here, the wolves said.

I’m so awfully sorry, the Lord said.

Thank you for inviting us to participate in your plan anyway, the wolves said politely.

The Lord did not want to appear addled, but what was the plan His sons were referring to exactly?

FATHERS AND SONS

God often appears addled in these stories, a figure of comic ineffectuality. He waits in line at a pharmacy for a shingles shot and is peppered with bureaucratic questions: “Have you ever had chicken pox?”; “How did you hear about us?” In a different story, the Lord “had always wanted to participate in a demolition derby,” but participation is determined by raffle and God’s name has never been called: “If He hadn’t been the Lord, He would have suspected someone was trying to tell Him something.” In yet another, the Lord decides to adopt a turtle, only to be told that he will have to build an enclosure and so, horror of horrors, go to Home Depot.

NOT ALL THE stories in Williams’s book explicitly feature God. In fact, many appear to be as concerned with issues of grammar and diction as with theodicy and theology. In one story, a married couple argues over whether an experience should be described as “pantomnesia” (“Greek roots meaning ‘all’ or ‘universal’—panto—and ‘mind’ or ‘memory’—mnesia”) or “déjà vu” (which “simply means ‘already seen’”). In another, a child wants to name its pet rabbit Actually, but the parents are resistant: “It was the first time one of our pets was named after an adverb,” and they “thought it to be bad luck.” Why? It’s not spelled out, but perhaps because the adverb seems distanced from the world, neither a thing nor an action. The final paragraph reads: “Everything proceeded beautifully, in fact, until Actually died.”

But even these stories of grammar and language, Williams suggests, are in a way stories about God, because to speak of God, to write stories about the Lord, is to be confronted by problems of language. How do you speak of that which simultaneously exceeds and serves as the very grounding of language? That’s the crucial challenge for all theological writing, and it is expressed explicitly at the very center of Ninety-Nine Stories of God, in story #49: “One should not define God in human language.... We can never speak about God rationally as we speak about ordinary things, but that does not mean we should give up thinking about God. We must push our minds to the limits of what we could know, descending ever deeper into the darkness of unknowing.”

Toward the end of the collection, Williams quotes from Simone Weil’s notebooks. There, Weil expresses her desire for, and feelings of inadequacy before, the Lord: “How could he love me? And yet deep down within me something, a particle of myself, cannot help thinking with fear and trembling that perhaps, in spite of all, he loves me.” Whenever we talk about God, we’re also talking about language and desire, absence and absurdity. Williams’s book suggests that the reverse is true as well: whenever we talk about language and desire, absence and absurdity, we’re talking about God, whether or not we know it.

I SUSPECT THAT Mary Rakow doesn’t need to be reminded of how fruitful a prompt to literary writing theological thinking can be. After all, Rakow knows her God-talk, having received a master’s from Harvard Divinity School and a Ph.D. in theology from Boston College. Her latest and second book, This Is Why I Came: A Novel (Counterpoint, $24), bears more than a passing resemblance to Ninety-Nine Stories of God. Though Rakow classifies This Is Why I Came as a novel, it proceeds, like Williams’s book, by anecdote and story, often condensing religious narratives of great weight and significance into a single page or two. Like Williams, Rakow gives us a God who can be weak (sometimes comically so) and fearful (often painfully so). In Rakow’s novel, God isn’t just absent; he is hiding. In one story, for instance, a character sees “God walk away until he came to an empty throne, seraphim and cherubim carved in linden wood, plated in gold, and instead of seeing him mount the throne he watched God crouch behind it, hidden.” This Is Why I Came is a story of definite abandonment and possible reconciliation, and it shows how feelings of bereavement and hopefulness might give rise to both theology and literature.

If Williams’s book is a miscellany—a cobbled-together assemblage of parable, story, and non sequitur—Rakow’s is more straightforward. This Is Why I Came begins with a narrative frame. A lapsed Catholic woman named Bernadette has come back to Mass “after an absence of many years.” Her faith was once a comfort but it hasn’t been for a long time. She is angry, doubting, “always afraid and worrying.” Appropriately, it is Good Friday. As Bernadette approaches the confessional, she holds what she describes as a “little hand-made book” stuffed with “images cut from magazines, art museum catalogues, photocopies from art books in her home.” It is really, though, “a Bible of her own”—that is to say, Bernadette’s idiosyncratic and heterodox retellings of the major stories of the Old and New Testaments. The rest of This Is Why I Came presents us with these Biblical recastings: Cain’s murder of Abel; Noah’s building of the ark; Jesus’s baptism; the raising of Lazarus; and many others, forty-seven in all.

Two questions immediately present themselves to the reader: Why would Rakow rewrite the Bible, and how does her version differ from its source? The first question is easily answered: Rakow looks to Biblical narratives because the Bible is, for the Western imagination, a great fount of storytelling, an almost limitless source of drama and pathos. Particularly in the Old Testament sections, Rakow wonderfully imagines how it might feel to live one’s life in a time of miracles and prophecy, when characters can’t do anything without thinking of, and worrying over, God’s demands: to multiply, to build an ark, to sacrifice a son, to proclaim righteousness.

Such demands are often unpleasant. To repurpose Wordsworth, painful was it in that dawn to be alive, but to be God’s chosen was very hell! Rakow’s Jonah, for instance, feels “as if he [were] being dragged around by God and his ever-increasing need to be loved”—to be loved both by Jonah, his prophet, and by the people Jonah exhorts to “realize [that] repentance was necessary.” Moses, longing to hear God’s voice and feel God’s love, desperately justifies why he doesn’t: “He knew if he let disappointment come, he would crumble, so he told himself, it’s better this way. Perhaps the invisibility of God is a sign of mercy. Not only mercy but magnam misericordiam. Great mercy.” Isaac, barely escaping sacrificial death, ever afterward “had nightmares that became dreams in daytime, no longer requiring darkness but stood firm against sunlight, that real.”

When we get to the New Testament, Rakow spends pages with Joseph, focusing on his bewilderment when faced with a wife and son who seem to signify “the jolting arrival of a completely new kind of time”:

They seemed unconcerned with happiness, which he held as life’s greatest gain, a true measure of the spiritual life. Life was made for joy, after all. And he did not take it for granted much less devalue it as they seemed to do. He looked at them as they walked ahead, feeling how keenly he wanted a simple life, a life without the supernatural in it.

These stories, both Old and New, are awash in dread and terror and beauty. They aren’t lifeless myths; they are mythic stories once again given flesh and blood.

SO WHAT IS different about Rakow’s version? In a certain sense, not much—or, at least not much that will surprise anyone who has read other recent recastings of Biblical narrative, Frederick Buechner’s The Son of Laughter, for instance. God here can be petty and tyrannical and utterly mysterious, but any reader of Buechner or Harold Bloom (or the Bible itself) will already know this. I suppose that the scope of Rakow’s enterprise is different. She isn’t just retelling a single Biblical story, à la Buechner; she’s retelling the entire Bible.

But what really makes Rakow’s retelling fresh, I think, is her incessant focus, like Williams, on the darkness of God—on hiddenness and absence as a constitutive part of religious experience. All theology, and all theological fiction, is a matter of emphasis: Do you emphasize God’s transcendence or his immanence? The problem of evil or the experience of grace? Rakow prefers, or at least finds it necessary, to dwell in divine absence. Around the time of Noah, God looks out at the world and sees emptiness: “instead of love, like himself, he saw wickedness and it grieved God. He had trouble seeing himself in the breeze, in the pony’s hide, in the daffodil and most of all in man, where the heart was so powerful for ill.” We all know how it feels to see the world not as sacrament but as vacuum. In Rakow’s retelling, God experiences this nullity, too, seeing his once-beautiful creation as, in Philip Larkin’s words, just “deep blue air, that shows / Nothing, and is nowhere, and is endless.” Later, Mary Magdalene thinks, “All good men go away,” and she is right: Jesus does depart, even if he promises to come again. Zaccheus “keep[s] a jar of water for [Jesus], even though he doesn’t come. Sometimes I call him ‘The visitor who doesn’t come.’”

At the end of the novel, we are yanked back out of divine history and into the narrative present. Bernadette goes to confession, where she admits, “I don’t feel I am committing a sin that I can’t believe in God anymore. I can’t will it. What happened, happened. But I really wish it would change.” To which the priest responds, in words that I suspect both Williams and Rakow would assent to, “It’s not a sin to refuse to believe in a God who’s too small…. To doubt the God you believe in is to serve him. It’s an offering. It’s your gift.”