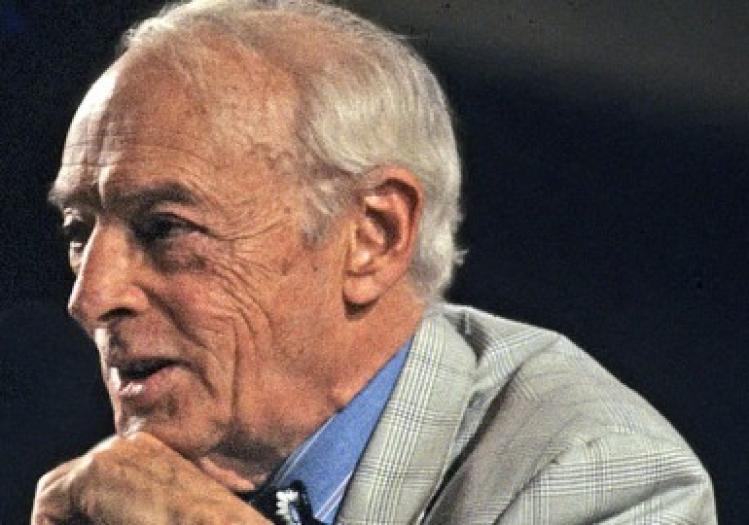

Saul Bellow is arguably the greatest American novelist since World War II. His best works—The Adventures of Augie March, Herzog, and Humboldt’s Gift—offer varied and lasting delights: they’re smart and funny, philosophical and lyrical, committed to the body and to the mind, one part Joyce to two parts Dostoevsky. It’s safe to say that if American literature is taught a hundred years from now, Bellow will be on the syllabus.

Bellow’s literary greatness is indisputable. So, however, were his personal failings. He was married five times, and it’s easy to see why. He cheated and chased women, leaving numerous ex-wives and children in his wake. Sensitive and vindictive, Bellow didn’t suffer fools gladly and, as he got older, he seemed to think that just about everyone—political liberals, multiculturalists, “Ivy League catamites,” former friend Alfred Kazin—was a fool. For such a generous writer, Bellow could be an extraordinarily selfish man.

Saul Bellow’s Heart: A Son’s Memoir (Bloomsbury) is an attempt by Bellow’s firstborn son, Greg, to come to terms with his late father’s flaws. The memoir opens in 2005. Saul has just died, and Greg is raging against the “flood of obituaries” that has immediately followed. Martin Amis, Leon Wieseltier, Philip Roth—all have publicly claimed Saul as an intellectual and literary father, and Greg is upset: “What is it with all these filial narratives?” he complains. “After all, he was my father! Did they all have such lousy fathers that they needed to co-opt mine?”

This childish rant raises some interesting questions. Who does a great writer belong to—the world of letters or his family? What is the relation between a writer’s private and public selves? And, finally, what are we to do with our lousy fathers? Greg tries to work through these questions, first by rereading all of Saul’s work (Greg thinks of this as “sit[ting] shivah”) and then by writing a history of Saul’s family life, moving from childhood to fatherhood to his final, happy marriage to Janis Freedman. (When they wed, Bellow was seventy-four and Freedman thirty-one.)

We are first introduced to Saul’s father, Abram Belo, a sometime bootlegger and full-time bullshitter who, Greg writes, “was a raconteur, a glib and entertaining fellow who was good to have around, though better at telling a story than at strenuous labor.” At the age of nine, Saul moved with his family from Quebec to Chicago. There, in the city streets and at the library, he discovered a love of language in all its forms, both the slang of hoodlums and the periodic sentences of Edward Gibbon. If Saul was at home in the polyglot city, though, he was increasingly alienated from his family. Abram moved from scheme to scheme, eventually becoming the owner of a profitable coal company. Saul rejected his father’s pleas to enter the family business. Art, not commerce, would be his calling.

The first section of Saul Bellow’s Heart isn’t particularly interesting. Too often Greg’s reading of his father’s early life sounds like an Introduction to Psychology lecture. He shallowly claims, for instance, that Saul’s “choice to pursue a literary life was his version of the epidemic of self-interest that took over the Bellow family after [Saul’s mother’s] death.” As this quotation makes clear, whatever else Greg may have inherited from his father, he didn’t get his facility with the written word.

The memoir begins to show signs of life, though, when Greg moves on to his personal relationship with his father. Saul’s occasional acts of kindness are remembered fondly. Saul and Greg go to the Met together. They attend triple features of the Marx Brothers. They share ice cream in Italy and talk about the “bare facts” of existence. After separating from Greg’s mother and decamping to Nevada, Saul sends his eight-year-old son a “fragrant sprig” that Greg keeps by his bedside as a reminder of his father “during his long absence.”

These absences, however, soon became longer and longer. Like Augie March fleeing those “reality-instructors” who would impose their worldviews upon him, Bellow distanced himself from his first, then his second, then his third, then his fourth family. Escaping from obligation and lighting out for the territory—this is the classic trope of American literature. But while such escapes make for good fiction, they also make for bad fathers. For years at a time, Greg and Saul appear to have barely had a relationship.

What emerges from Saul Bellow’s Heart is a simple, depressing truth. Saul could be a good father, but only when he wanted to be, and he only wanted to be when it was convenient. No matter how Greg tries to finesse it, Saul seemed to care more about his novels (and his many romances) than about anything else, family included. That, it could be argued, is one of the reasons he was such a great writer: selfishness may be a moral failing, but when it’s connected to a devotion to one’s craft, it can be an artistic gift.

“Maybe that, really, is as good a definition as any of an artist in the world: a ruthless person.” This is the lesson of Saul Bellow’s Heart, but the quotation actually appears in a different work: Claire Messud’s novel The Woman Upstairs (Knopf).

The book is narrated by Nora Marie Eldridge, a forty-two-year-old single woman who teaches elementary school in Cambridge, Massachusetts. In the opening chapter, Nora describes herself as being so close to average as to approach nullity: “Neither old nor young, I’m neither fat nor thin, tall nor short, blond nor brunette, neither pretty nor plain.” While in high school, Nora decided to become an important artist—“It was supposed to say ‘Great Artist’ on my tombstone”—but she has settled unhappily for a different life. She continues to work on her art on weekends and at night, but with little hope of ever showing it to the world. (At the beginning of the book she is working on a “tiny replica of Emily Dickinson’s Amherst bedroom.” This will be the first in a series of detailed recreations of places of female confinement.)

Into this cramped world comes the Shahid family. First, Nora meets Reza, a new, eight-year-old student who looks like “a child from a fairy tale.” Next, she meets Sirena, Reza’s mother and an artist—a charming Italian beauty whose work has been shown at important galleries. Finally, she meets Skandar, Sirena’s husband, a Lebanese professor interested in the ethics of historical narrative.

The Shahid family exudes charisma—they are successful, exotic, and sexy—and Nora falls for them hard. She struggles to articulate just how magical the family, especially Sirena, appears, and how this magic seems to rub off on herself:

This was the miracle of my first Shahid year. Never, in all my life, had I thought, as I did then, This is the answer. Not once, but over and over in different configurations, the answer to not one but to every question that seemed to come in the course of that year, like music.

Sirena invites Nora to rent an artist’s studio with her, and they work side-by-side, sharing coffee and discussing art. Nora’s friends suspect that she harbors a crush on Sirena, but Nora doesn’t care. All she knows is that her real life, the life she was always supposed to live, has finally begun.

However, almost as soon as she falls in love with the Shahids—and this novel is, above all else, a love story—cracks begin to appear. Nora’s infatuation with Sirena soon shades into obsession, and Sirena isn’t above exploiting this fact. First, she asks for Nora’s help on her own installation project. Then, one night, she begs Nora to look after Reza while she and her husband go out. Soon, Nora, the supposed friend, is serving as a regular unpaid babysitter.

Nora doesn’t feel taken advantage of. Is being used so terrible if it’s in the service of a great artist? Is being exploited so wretched if it allows Nora to experience some of her friend’s glamour and success? But we know that this story can’t end well. Nora loves Sirena and finds her presence transformative; Sirena likes Nora and finds her presence useful. The novel builds toward a moment of shocking betrayal.

I’ve described The Woman Upstairs as a dreadful progression from love to betrayal, but that isn’t quite right. Nora tells the story retrospectively, and this requires a complex layering of tones and temporalities. Messud needs to make us feel, wholly and completely, Nora’s infatuation with the Shahids while at the same time allowing Nora’s anger to subtly poison the love story. Gone are the Jamesian filigree and social comedy of Messud’s previous novel, The Emperor’s Children. In their place is an atmosphere of dread and bitterness portending violence. As Nora claims, “to be furious, murderously furious, is to be alive.”

Messud uses a line from Philip Roth’s Sabbath’s Theater as one of the novel’s epigraphs: “Fuck the laudable ideologies.” The Woman Upstairs does something more complicated than Roth’s cri de coeur suggests. It shows us the attractiveness of certain ideals—the noble artist; the beloved—while at the same time showing us what happens when these ideals fail to live up to their promise. Messud (who’s married to the critic James Wood, with whom I studied in college) knows that we’re attracted to the beautiful and successful precisely because they’re not like us. Even more, we’re attracted to them because they know that they’re not like us, and because they’re willing to use this fact for their own, more glamorous purposes. In being used by the successful, we seem to become part of their success, and that, for many, is reason enough.

Reading The Woman Upstairs is a bit like biting into a seemingly ripe apple and finding it rotten to the core. Reading James Salter’s All That Is (Knopf), by contrast, is like feasting on crème brûlée. This novel is delicate, delicious, and just a little bit guilt-inducing.

The eighty-eight-year-old Salter, who was once a friend of Saul Bellow’s, is a highly regarded—if too infrequently read—master of contemporary literature. Many readers swear by A Sport and a Pastime, Salter’s 1967 novel of transcendent longing and explicit, rapturous sexual abandon in postwar Paris. Others, including myself, prefer Light Years, a haunting 1975 novel that traces the dissolution of a marriage over time.

In Light Years, Salter offered what could serve as his aesthetic credo: “Life is weather. Life is meals. Lunches on a blue checked cloth on which salt has spilled. The smell of tobacco. Brie, yellow apples, wood-handled knives.” Salter’s work centers on sensual experience—sex, physical labor, food, and drink. But in a Salter novel, sex is never just sex and food is never just food. They are the most meaningful and potentially sacred things we are capable of experiencing. For his fans, no one has a better ear for the music of a short, chiseled sentence and no one better describes the pains and ecstasies of physical embodiment. For his detractors, no one squanders these stylistic gifts on such frivolous topics.

All That Is is Salter’s first novel in thirty-four years, and its opening seems to mark a departure. History has rarely made itself felt in Salter’s work. In the past, he’s been interested in how the general passage of time marks an individual life—how an affair becomes stale, how physical prowess weakens—but not in how large historical forces make themselves felt in our daily existence. All That Is, however, opens with a young American naval officer named Philip Bowman engaging in a battle off Okinawa in 1944. Ah, we think, Salter is doing something different here! But within ten pages, the battle is over, the war has ended, and History, we realize, has been dispensed with.

The rest of All That Is follows Bowman’s life over the decades. He becomes an editor at a New York publishing house, journeys to Europe, buys a summer home, eats rich food, and sleeps with several different women. As always, Salter describes these sexual experiences with a blend of lyricism and explicitness that recalls D. H. Lawrence. For Salter, there is no separating the transcendent from the earthly, the sacred from the sexual.

Salter is an expert employer of what Henry James called the “scenic method.” All That Is is really a string of brilliant scenes, loosely held together by Salter’s prose style and the general arc of Bowman’s life. Characters drift in, hold center stage for a page or two, then drift off again. The pacing is languorous, the prose simple, beautiful, and frequently moving: Bowman and a lover wake “to the fresh light of the world.” As he flies into London for the first time, Bowman looks out the window: “In the morning there was London, green and unknown beneath broken clouds.”

All That Is is longer than most of Salter’s previous work, and it covers a longer period of time. Sometimes I found my eyes glazing over: another New York literary party? Another love affair? It’s also old-fashioned, and not in a good way: it’s a luxurious, white, male world, and women exist within it primarily to be slept with. At one point, an older Bowman engages in a love affair with a younger woman that is so brutal as to border on sadism, but we are (I think) meant to forgive him almost immediately.

This isn’t to say that Salter the stylist has flagged; he hasn’t. There are plenty of lines and images to savor. While the typical Bellow sentence is enlarged, cascading from one clause and register to the next, the typical Salter sentence is hard and gem-like: “The water was a dusty green, pure and silky with a gentle sway.” If Saul Bellow’s Heart shows that aesthetic and moral goodness are different matters altogether, and if The Woman Upstairs argues that cruelty and success often go hand-in-hand, then All That Is offers a more comforting reminder: that despite selfishness and cruelty, there is still much beauty to be discovered in the world.