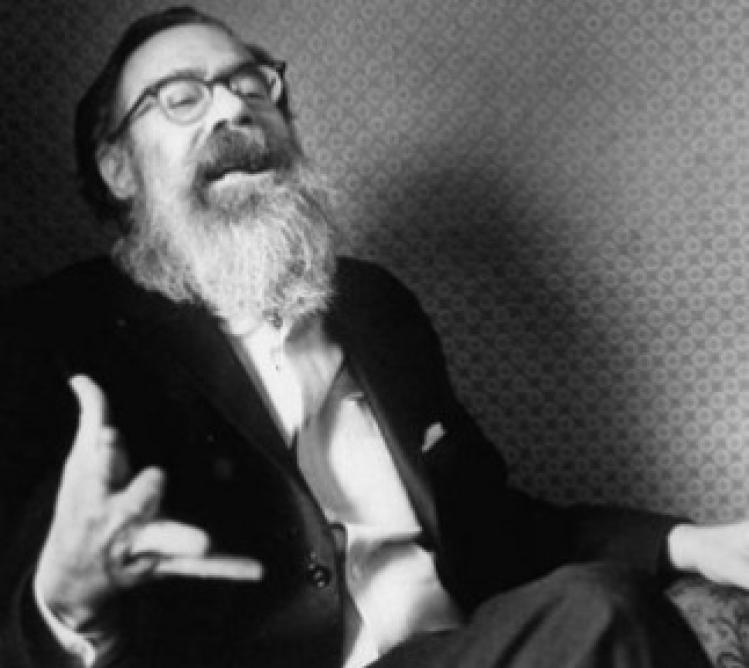

On the morning of January 7, 1972, John Berryman, bearded and stoop-shouldered, trudged across the campus of the University of Minnesota in gelid Minneapolis before halting on a cement pedestrian walkway above the Mississippi River. He balanced himself on the metal rail, much as his hero Hart Crane had balanced on the stern rail of the S. S. Orizaba forty years earlier. Then, like Crane, he waved goodbye to those around him, before pushing forward and plunging into the unforgiving void below. He was fifty-seven years old.

Berryman was in Alcoholics Anonymous and had been dry for eleven months. But shortly before that January day, he had started drinking again. Two days before his death he had scribbled out one last poem, explaining how he meant to escape yet one more disappointment—the lectures he had prepared for the class he was going to teach that semester had fallen far short of his own expectations, and he anticipated students

dropping the course,

the Administration hearing

& offering me either a medical leave of absence

or resignation—Kitticat, they can’t fire me—

He had a better plan for keeping everyone off his back: a simple tilt forward and he could escape all that.

Berryman’s troubles began early: with the death of his father, John Allyn, when Berryman was just eleven. At the time his family was living in an apartment down on Clearwater Island in Tampa Bay. His mother, Martha Smith, had begun carrying on an affair with a janitor, and his suicidal father had found accommodations elsewhere. There were arguments, scenes, and recriminations out in the hall beyond the boys’ closed bedroom door. Then, early on the morning of June 26, 1926, his mother walked into their room to tell them that their father was dead. His body lay spread-eagle in the alley behind their apartment. Apparently he had shot himself in the chest. Afterward, Martha and the janitor, who was twenty years older, married and moved with her sons to Queens, New York. The janitor’s name was John Berryman, and the boys were told that they would be taking his last name. Years later, Martha would tell the old man that it was time to move out, and after he did, she tried to reinvent herself, instructing her son John to tell his friends that she was not his mother but his older (and single) sister.

Later in his life, Berryman wondered if his mother and stepfather hadn’t killed his father and left the gun near his body. No wonder he obsessed over Hamlet’s play within a play, in which the death of Hamlet’s father is rehearsed on stage before his mother and her new husband, the usurper king. Berryman once went so far as to invite his mother to hear him lecture on Hamlet while he was teaching at Princeton, hoping it might draw her out, but, as usual, she coolly avoided that well-laid trap.

Berryman’s obsession with the father he’d lost as a boy followed him all his life, before, during, and after he composed the more than four hundred poems in his brilliant Dream Songs. The second-to-last of the published collection begins this way:

The marker slants, flowerless, day’s almost done,

I stand above my father’s grave with rage.[...]

I spit upon this dreadful banker’s grave

Who shot his heart out in a Florida dawn

O ho alas alas

When will indifference come, I moan & rave

This brought to a tentative end what the first Song had begun. There, writing in the voice of his alter-ego Henry, Berryman described his early and prolonged reaction to his father’s death:

Huffy Henry hid the day,

unappeasable Henry sulked.

The day his father died changed everything forever: from then on, nothing—nothing—ever “fell out as it might or ought.”

As a boy in Oklahoma, and before his family moved to Florida, Berryman had served each morning at the early Mass with Fr. Boniface, the two of them up there by the small pre–Vatican II altar, intoning the Latin together—Introibo ad altare Dei—while elderly ladies knelt in the pews behind them. And he had been happy.

With the death of his father, his other Father, the one to whom he had prayed, also seemed to withdraw, receding into the shadows of literature. That Father, too, had seemed to abandon him, and so Berryman left the thought of him behind, making his way in life with whatever was at hand. Sex, adultery, booze, high-talk among his intellectual peers about the state of the world. He would read everything: the classics, the Bible (as literature), his worthy contemporaries. After living for a year in England, he spoke with a quasi-British accent for the rest of his days. He had heroes—Hopkins, Housman, Yeats, Eliot, Pound—and his company of literary pals—among them Saul Bellow, Ralph Ellison, Delmore Schwartz, Robert Lowell, Randall Jarrell and Adrienne Rich—though he would do his damnedest to outshine them all. He made elaborate lists of living poets just to see how he and they were faring with the passage of time.

“I am obliged to perform in complete darkness operations of great delicacy,” Berryman wrote in one Dream Song. Many of these operations he’d performed on himself, reporting back what he had discovered about the human condition. Naturally, these were “operations of great delicacy” because they’d been performed in the shadow of death, and therefore of God. “Why did we come at all,” Berryman asks in a Dream Song in his fifty-second year:

consonant to whose bidding? Perhaps God is a slob,

playful, vast, rough-hewn.

Perhaps God resembles one of the last etchings of Goya.[...]

Something disturbed,

ill-pleased, & with a touch of paranoia

who calls for this thud of love from his creatures-O.

Perhaps God ought to be curbed.

Then, three years later, there came another life-altering change. It happened when he was hospitalized for extreme intoxication in the late spring of 1970. He found himself in a locked ward at a Catholic hospital, St. Mary’s. It was decided he was a danger to himself. He was informed by Jim Zosel, an Episcopal priest who was charged with looking after him and the others on the floor that, no, he could not take a taxi to campus so that he could teach his classes because every time he did, he cajoled the driver into stopping at a local bar afterward so he could refresh himself with half a dozen drinks before returning to the hospital to continue his treatment. But, since Berryman was teaching a course that included the Bible as literature that term, the priest volunteered to take over his class for him.

It was the discovery that someone could actually care enough about him to do such a thing that took Berryman by surprise—floored him in fact. And so his recovery began. He joined AA, acted as a sponsor to others, stayed off the booze “each damned day,” and began attending weekly Mass, though he remained acutely critical of the shortcomings—stylistic and otherwise—of the young priest’s homilies in these too-easy post–Vatican II days. At the time, Berryman had been assembling new poems in a post–Dream Song mode in an effort to remake himself—without much success. These poems were written in unrhymed quatrains that owed a great deal to the style of Emily Dickinson, as well as to the irreverent French poète maudit Tristan Corbière, who had died of consumption at twenty-nine—like Dickinson, an unknown figure at his death.

On the other hand, it had been a long time since Berryman himself was unknown. By the mid-’60s, he was in demand everywhere, having been showered with awards and prizes and rave notices in publications like Time and Life. Likewise, from his college days on, he had had his share of what he liked to call love. He meant to call the new volume he was finishing up then Love & Fame, and he was pleased—oh yes—with the part of it he’d already written.

And then came his new religious turn, which puzzled, amused, and disturbed the literary critics, as well as his fellow poets. The volte-face began abruptly with the “Eleven Addresses to the Lord.” If God was the “slob” he’d complained of earlier, the locked ward Berryman now found himself in was a nagging reminder of who the real slob really was. This new self-awareness in the face of recovery led in turn to a sense of overwhelming gratitude for having somehow been rescued. The first poem in the sequence begins:

Master of beauty, craftsman of the snowflake,

inimitable contriver,

endower of Earth so gorgeous & different from the boring Moon,

thank you for such as it is my gift.

A prayer of praise, then, followed by antiphons of thanksgiving—as with the Lord’s Prayer and the Psalms. But poem prayers with their own wry sense of humor: gallows humor, trench humor, perhaps, but funny and vulnerable. In the desert landscape of the moon’s surface (recently photographed up close by astronauts who had walked on that surface), Berryman had seen an image of his own soul’s desolate condition. Nothing for it, then, but to beg God to get him out of that hell: “You have come to my rescue again & again,” he sang now, “in my impassible, sometimes despairing years.”

Of course he still had questions. Given the human condition, he understood that he would always have questions. How did one love a God who was essentially unknowable? Did we live again after death? It didn’t “seem likely / from either the scientific or the philosophical point of view.” But who was he to say? One thing was clear: He was surer now than ever that “all things are possible to you.” He also understood that he was now ready to move on with “gratitude & awe,” hoping to “stand until death forever at attention / for any your least instruction or enlightenment.”

“Eleven Addresses to the Lord” is the cry of a brilliant and broken man who had come to admit that he, too, was in need of consolation. He thought of the broken witnesses who had gone before him—of people like St. Polycarp, disciple of John the Evangelist, who had been given the choice by the Roman authorities to deny Christ or be burned alive. And now Berryman recalled the old man’s astounding response:

‘Eighty & six years have I been his servant,

and he has done me no harm.

How can I blaspheme my King who saved me?’

Berryman ended his remarkable sequence with yet another prayer, a plea this time, that God would make him too somehow acceptable at the end,

in my degree, which then Thou wilt award.

Cancer, senility, mania,

I pray I may be ready with my witness.

And life went on much as before. In the winter of ’71 Berryman was at work on his own version of the Divine Office. This sequence, titled “Opus Dei,” opens his final, posthumous volume of poems, Delusions, Etc. At the beginning of this sequence, Berryman quotes Tolstoy’s “The Devil.” If the protagonist of that story, Berryman reminds us, “was mentally deranged, everyone is in the same case,” for the most mentally deranged are those “who see in others indications of insanity they do not notice in themselves.”

“With the human exhausted,” the critic Helen Vendler has written, “Berryman solicited the divine.” The religious poems he wrote near the end of his life, especially the ones in the “Opus Dei” sequence, were, Vendler insisted, simply no good. If Mr. Berryman had discovered a “newly simple heart” and new visions into the workings of his God,

whatever temporary calm they gave his soul, [they] gave no new life to his poetry, and the last two poems, particularly [“Vespers” and “Compline”], are intolerable to read…. When he became the redeemed child of God, his shamefaced vocabulary drooped useless, and no poet can be expected to invent, all at once and at the end of his life, a convincing new stance, a new style in architecture along with his change of heart. Berryman’s suicide threw all finally into question—Henry’s sly resourcefulness as much as Berryman’s abject faith. In the end, it seems, neither was enough to get through the day on, and even though a voice divine the storm allayed, a light propitious shone, this castaway could not avoid another rising of the gulf to overwhelm him.

Shamefaced. Abject. Vendler could not bear to see the old virtuoso brought low. But consider this: Writing as a broken man, Berryman had used all the resources still at his command, knowing that he could no longer take refuge in modernist irony. Or at least, knowing himself and his own old evasions too well, he was going to try his damndest not to. He had stuck to his old irony with others in the hospital who, like him, had hit rock bottom. But they, having heard it all before, had spotted at once the buzzing lies, false reconstructions, and obfuscations.

As he sweated over his final sequence, “gunfire & riot” were fanning “thro’ new Detroit.” Antiwar protesters were being tried, fined, and imprisoned. The world around him was in chaos, and so was he. He had made mistakes. His body was a wreck. But he would bear witness in this terrible time, in and all around him, as best he could. He hoped and prayed that Origen was right after all and that hell was either “empty / Or will be.” Given human nature as he knew it, sin seemed inevitable, and, yes, humanity would suffer for it “now & later / but not forever, dear friends & brothers!”

It is mid-winter in Minneapolis as he sweats over these lines. At the moment, he understands, there are “no fair bells in this city,” and, in truth, his house, with his wife and two daughters asleep, feels as cold as the darkest corner of his mind. Still, he must continue his conversation with the God who, he now knows, had never really abandoned him. And he prays that if somehow he should fall at last from some terrifying height, the same God he is speaking to will be there to hold him up. After all, he has fallen often before, into addiction and madness, and has somehow been caught. And so he waits out the dark nights of another winter, and another dark night for his soul.

This article was adapted from an essay that will appear in Not Less Than Everything: Catholic Writers on Heroes of Conscience, from Joan of Arc to Oscar Romero, to be published by HarperOne in February 2013.

Related: Tormented Witness, by Elizabeth Kirkland Cahill

From ‘Addresses to the Lord,’ by John Berryman