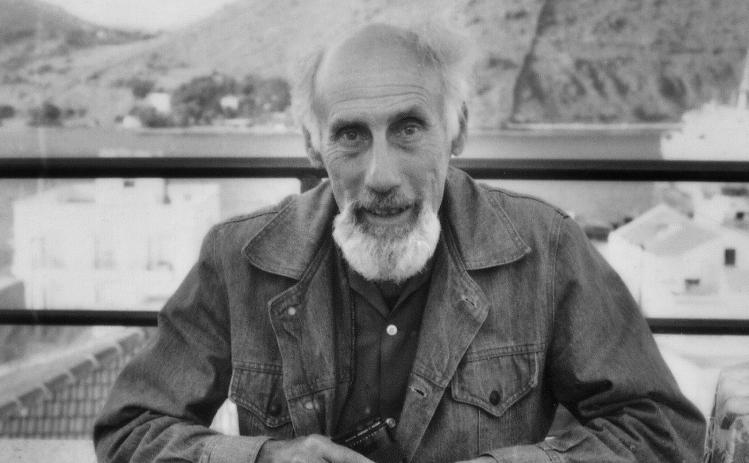

Robert Lax was many things—a mystic, a poet who used simple words to express profound thoughts, a world traveler who made friends wherever he went, a convert from Judaism to Catholicism who valued both traditions. The Wikipedia article devoted to him lists his occupation as “Clown, Professor, Writer.” Many more designations could be added. Perhaps the best short description of his life is something he wrote himself in the first lines of his best-known poem, “Circus of the Sun”: “Sometimes we go on a search / and do not know what we are looking for, / until we come again to our beginning.”

Lax sought truth and wisdom in both mundane and spiritual forms. His search began in Olean, a small town in western New York. His travels finally took him to the Greek islands of Kalymnos and Patmos, almost twelve thousand miles from Olean. For most travelers it is a two-day car, plane, and boat trip each way. Culturally, it is even farther. It took Lax a lifetime to get there. Born to immigrant Jewish parents on November 30, 1915, he died back in Olean in 2000, a few months before his eighty-fifth birthday.

Lax produced not only poems and prose but also graphic and performance art, video, film, and photography. His work was well known in his lifetime by a select group of writers and artists in Europe and America and by many more who read The Seven Storey Mountain by Thomas Merton, a great friend and admirer.

Now, twenty-one years after his death, Lax may well become better known for an unusual combination of art forms: opera and the circus. In what promises to be a major musical event, his poetry will be sung and spoken in composer Philip Glass’s new two-act opera, Circus Days and Nights. The opera—a collaboration between Malmö Opera and Cirkus Cirkör, a small Swedish circus—is scheduled to open in Malmö, Sweden, on May 29 and run through June 13 before an international tour. The initial run is being live-streamed for a limited number of attendees. (Tickets are available online.)

Glass obtained the rights to set Lax’s poems to music several years ago, but lacked a circus to perform in it. He found his circus in 2016, when Cirkus Cirkör, together with Folkoperan, performed Glass’s opera Satyagraha in Stockholm and the Brooklyn Academy of Music. This is one of Glass’s three “portrait” operas. It is fitting that Satyagraha brought Glass together with the circus that will perform in Circus Days and Nights. The main character of Satyagraha is Gandhi during his years in South Africa, when he was developing his commitment to nonviolence. Satyagraha in Sanskrit means “devotion to truth.” Both concepts, truth and nonviolence, were key to Lax’s life and work. And both Glass and Lax had immigrant Jewish parents.

Glass says in a video about the opera that it “took the musical language I know and combined it with the movement language of the circus. It is a story about storytelling—that’s what we know. In the beginning there was storytelling around a fire. That became traveling shows, circus, and opera.” Glass’s collaborators are the playwright David Henry Hwang and the artistic director of Cirkus Cirkör, Tilde Björfors. Hwang is best known for M. Butterfly and as a collaborator on four previous Glass operas. He didn’t know Lax’s poems before Glass gave them to him, but he was moved by “their beauty, simplicity, and profundity.” Björfors directed the production and collaborated on the libretto. She says that she had read Lax’s circus poems and was eager to work with Glass when she met him.

Cirkus Cirkör is a “contemporary” circus. Few animals are included, and circus skills are used to develop character and story. Circus Days and Nights will feature performers and roustabouts who dedicate themselves to this art, capturing a day in their lives as a spiritual ceremony honoring the cycle of life and death.

The collaborators used Lax’s book Circus Days and Nights (Overlook Press, 2000) as the basis for the libretto; it includes his poems “Circus of the Sun,” “The Book of Mogador,” and “Voyage to Pescara.” In the opera Lax himself is a character—two, in fact: the Poet as a Young Man and the Old Poet. Glass’s music, which he describes as “repetitive structures” (a term that could also be applied to Lax’s poetry) will be played by a seven-person ensemble from Cirkus Cirkör, led by an accordionist and including cello, violin, clarinet, trumpet, brass trombone, and percussion. There will be circus acts, choruses, colorful costumes, and all the magic that comes with a mixture of these two visual and aural art forms.

The Poet as a Young Man will likely describe Lax’s travels with a real circus, recounted in “Circus of the Sun” and “Book of Mogador.” But his attraction to circus began much earlier, when he was a child. In the 1920s, Lax’s father woke him early when the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus train came to Olean. They watched the train unload and chatted with the performers. It was a classic small-town American experience that could have been the subject of a Norman Rockwell painting. (Or, given his father’s Eastern European Jewish roots, perhaps one by Marc Chagall.)

As Paul Spaeth, who oversees the Lax archives at St. Bonaventure University near Olean, writes in his introduction to Circus Days and Nights, “Lax, the reporter seeing things with childlike grace, at times relates his vision like an Old Testament prophet, at times like St. Francis composing a new ‘Canticle of the Sun,’ and at times like a kid wandering through the circus grounds eating popcorn.” The awe and wonder Lax experienced as a child meeting circus people never left him.

Lax’s work is often described as being in the “Judeo-Christian tradition.” He converted to Catholicism in his late twenties but regarded his Jewish heritage as fundamental to his identity. Judith Emery, a friend of Lax who has edited a book based on tapes she exchanged with him over several years, says, “Bob told me more than once, ‘If I could not be a Jew and a Catholic, I wouldn’t have become a Catholic.’” Lax sometimes described himself as “post-denominational.” In his biography of Lax, Pure Act: The Uncommon Life of Robert Lax (2015), Michael N. McGregor writes that “in trying to explain his conversion near the end of his life Lax spoke of the long Catholic tradition.” Lax’s sister Gladys thought he felt drawn to the Church’s intellectual tradition, a common reason for conversions among intellectuals in the 1930s.

Lax’s deep friendship with Thomas Merton, a Catholic convert who became a Trappist monk, certainly influenced his own conversion. But some seeds of both his fidelity to his Jewish heritage and his attraction to other forms of spirituality may have been planted in his youth in Olean. His parents, Sigmund (Siggie) and Rebecca (Betty) Lax, moved there from New York City to take over a family clothing business. Betty missed the music, art, and theater of New York City, and the family moved back and forth from Olean to Long Island. A talented vocalist, Betty often sang at local churches. She and her daughter, Gladys, were the first women allowed to take courses at nearby St. Bonaventure College, a Franciscan institution. Lax accompanied Betty on some of those visits.

Lax’s family was active in Olean’s small Jewish community. His mother helped raise money for the rose window that is a prominent feature of the B’nai Israel Temple, though the building is no longer used as a synagogue. Gladys married Benjamin Marcus, a son of H. W. Marcus, a prominent Jewish leader and businessman in Olean. The family moved easily in both Jewish and Gentile social circles.

As an undergraduate at Columbia, Lax studied literature with Mark Van Doren and was an editor of the Jester, the college humor magazine. Lax’s gifts as a writer were recognized not only by Van Doren but also by Jacques Barzun, the noted cultural historian. In addition to his studies, Lax read widely at the nearby Jewish Theological Seminary. He built strong friendships with Merton, the painter Ad Reinhardt, and the journalist Ed Rice, among others. During the summer after graduation in 1938, the group lived and worked in a large cottage owned by the Marcus family in Rock City, near Olean. Other writers joined them for short stays. They also spent time at St. Bonaventure.

Lax moved around a lot. He worked at the New Yorker, which also published some of his poems; he reviewed movies for Time and contributed articles to Parade and the short-lived Catholic magazine Jubilee. He volunteered at a homeless shelter in Harlem. Later, he worked in Hollywood as a screenwriter for a forgotten movie called Siren of Atlantis. During his Hollywood stay, he spent a lot of time in conversations with the theosophist Henry Hotchner, an uncle on his mother’s side of the family.

Lax traveled widely in Europe and the United States and taught at several colleges, but periodically returned to Olean to recuperate from anemia and arthritis. Olean offered the closeness of family, the community of St. Bonaventure, and freedom from the commercialism and frantic pace he disliked about New York City.

In 1943, when Lax was working at the New Yorker, he accompanied his friend Leonard Robinson on an assignment to write about the Cristiani family, members of a small Italian circus then visiting New York. Lax was fascinated by the Cristianis, and especially by Mogador, a skilled acrobat and equestrian. After that initial meeting, Lax kept in touch with the family and in the summer of 1949 traveled with them through western Canada. He learned to juggle and sometimes performed as a clown. As he did throughout his life, he kept notes and reflections during the trip. To turn these notes into poetry, Lax needed to find a quiet space to write. He turned to Olean, and spent the spring of 1950 in a room in the lower level of the St. Bonaventure library working on what became “Circus of the Sun.”

On one level the poem is a description of a day in the circus—coming to town, setting up the tents, rehearsing, performing, and shutting down at night, rising at dawn to begin another day of travel. But on a metaphorical level, the poem retells the story of Genesis, in which the circus recreates the formation of the world, acrobats become “God’s chosen people,” and the traveling circus and its movable tents become the Israelites following Moses into the desert. In a section called “The Morning Stars,” Lax writes:

We have seen all the days of creation in one day: this is

the day of the waking dawn and all over the field the

people are moving, they are coming to praise the Lord:

and it is now the first day of creation. We were there on that day

and we heard Him say: Let there be light. And

we heard Him say: Let firmament be; and water, and

dry land, herbs, creeping things, cattle and men.

The section that came to be known as “Sunset City” (untitled in the original) is different from the preceding and following sections. It has a strong rhythmic pace, word repetitions, and vivid images. The British critic R. C. Kenedy called it “one of the greatest poems in the English language.” Here are its opening lines:

The sunset city trembled with fire, the air trembled

in fiery light, a fiery clarity stretched west across the

walks, the tongues of air licked up the building sides, the

wings of fire hovered over the churches and houses, steeples

and stores of the wide flat city that stretched to the sea.

In one section of the poem, Mogador responds to Penelope, the tightrope walker, who asks how he lands so gracefully after a somersault on horseback. He refers to the dark cloud that enveloped Moses on Mount Sinai.

It is like a wind that surrounds me

or a dark cloud,

and I am in it,

and it belongs to me

and it gives me the power

to do these things.

It took several years to complete “Circus of the Sun” and even more time to find a publisher. In one of the many happy coincidences in Lax’s life, he met Emil Antonucci, a graphic designer in New York who was instrumental in the redesign of Commonweal in 1964 and again in 1987. Antonucci loved the poem and created a publishing company called Journeyman Press to publish an edition of just five hundred copies with his own illustrations. He used a small hand-operated press to print the book, which was paid for with funds from a Guggenheim grant. Several illustrated editions have been published since then, and the poem has been translated into German, French, and Italian.

In the 1950s Lax traveled around Europe, staying for a time in Paris, making new friends among literary people but also among the workers he met on the streets and in cafés. He wanted to strip his life and his work down to the essentials, and lived as frugally as possible. He stayed for several months in a poor neighborhood of Marseilles. In 1962, he moved to the Greek island of Kalymnos, where he found hospitable people and cheap living quarters. Kalymnos seemed ideal for several years, until his neighbors became suspicious of him during a conflict between Greece and Turkey. They thought an American who wrote in a notebook and took lots of photographs must be a spy.

After a long period of indecision, he moved to Patmos in 1986. Patmos offered everything Lax needed—a small house and time to write and think, with the sun, sea, and sky always in view. Reversing the pattern of his earlier years, when Lax had gone to Olean for rest and recuperation, Olean came to Patmos. He had frequent visitors—his family, especially his niece Marcia Marcus Kelly and her husband, Jack, and Marcia’s sister, Connie Brothers. Other cousins and relatives were welcome, as were people he had met or corresponded with in the United States and Europe. He was called “Petros” by his neighbors, and everyone on the island knew where he lived and directed visitors from the boat to his simple home on a hill.

These were quiet, contemplative years for Lax. Yet he continued his daily conversations with fishermen and other residents of Patmos. In an interview recalling his visits to Lax, Steve Georgiou, a professor of art and religion, said, “On our walks, we’d visit people who were sick. He’d put a chair by their bed, lean back and breathe his way into their existence. And I say that because the word for breath and spirit in Hebrew (ruach) is essentially the same.... In that coming together...Lax had the ability to make people feel better.”

Before he left Patmos for the last time, Lax asked his niece Marcia to make sure to bring a few precious items: an etching of St. Thérèse of Lisieux (“The Little Flower”) and The Way of the Jewish Mystics, a small-format book edited by Perle Besserman (1994). Lax died peacefully, as he had lived, in the town where he was born. His works live on to enchant and enlighten new generations of readers and to inspire new works of art, like Philip Glass’s Circus Days and Nights.