Those of us who work in higher education are accustomed to conservative thinkers painting us as the spoiled brats of the culture wars. At the other end of the political spectrum, radical students in elite institutions have sought to shout down even progressive academics when their demands are not being met. One comfort this brings is that when you are being challenged from both ends for different reasons, well, you must be doing something right. But William Egginton provides another and more solid comfort in his new book. Egginton, director of the Alexander Grass Humanities Institute at Johns Hopkins University, has impeccable credentials as a liberal professor but writes here with deliberate intent to stake out a centrist position. Higher education, he argues, has benefited enormously from identity politics because it has made the voices of previously silent or silenced groups much more audible. We are the better for the critiques of the establishment that have come from feminists and people of color, and also for the subdivisions within each of these groups. Sure, some of the more extreme voices have sometimes led us to faintly ridiculous extremes, the kinds of things that conservative journals like First Things and the New Criterion rejoice in excoriating. But on the whole the benefits that have accrued from the multiplicity of different voices have led to a saner and healthier academic and, indeed, national culture.

The problem for higher education today is not that identity politics is a part of academic culture, but that the healthy recognition of difference (to which we are indebted) has come at the price of inattention to the opposite good: the strengthening of the bonds of community that education in general, and the liberal arts in particular, have always existed to foster. The principal reason for this imbalance between the legitimacy of concern for the individual and attention to the common good, thinks Egginton, is the excessive individualism that has come to bedevil American public life. And this itself is a product of the neoliberalism of the market economy, which has affected those institutions that should stand at a critical distance from all ideologies. “Our universities,” he writes, “have become like department stores.” The pursuit of truth has been abandoned in favor of “branding, competition, and marketing themselves to a well-researched brew of the wealthiest and most academically stellar students.” Egginton may have to change his tune just a little in light of Michael Bloomberg’s recent gift of $1.8 billion to Johns Hopkins solely to support student aid: but until many other institutions are similarly graced, higher education in general will continue to reinforce the huge gap between the rich and the poor.

Egginton’s plea is only the latest in a long line of texts bemoaning the condition of American education. Many are from the right, like Heather Mac Donald’s The Diversity Delusion or Michael Rectenwald’s Springtime for Snowflakes. On the left there is Holden Thorp and Buck Goldstein’s Our Higher Calling or Robert Putnam’s more sociological analysis Our Kids. Though he is largely focused on universities, Egginton echoes Putnam’s distinctively liberal argument: that all this malaise begins at the earliest stages of education, where the dramatic differences of quality and opportunity between geographic areas or racial groups simply mean, in Egginton’s phrase, that inequality “is baked into the system.”

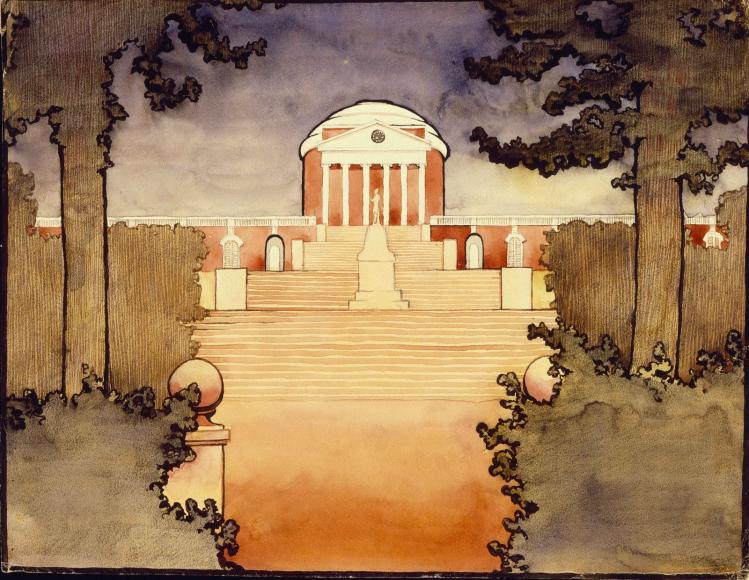

The solution to the crisis in education has to come from a reawakening on the part of progressive educators to the importance of community. Personal freedom without community responsibility only leads to the tyranny of authoritarian systems or the neoliberal market economy over the individual, who has neither power nor protection against them. What we need, he thinks, is a return to Thomas Jefferson’s insight that the best defense against the drift of power toward tyranny is “to illuminate, as far as practicable, the minds of the people at large.” Jefferson recognized that education gave people the skills to distinguish truth from falsehood so that they would be able to counter the ambitions of the powerful. Jefferson’s Virginia Bill 79, which sought to provide public education, was sadly defeated: but the idea he promoted, and the dangers of abandoning that idea, are as fresh to Egginton as they were to Jefferson.

Egginton focuses on elite private institutions. But to what degree does his critique extend to smaller schools, and in particular to church-related institutions like the many Catholic colleges and universities throughout the country? A neoliberal culture affects all civil society, and in particular the minds and mores of those of traditional undergraduate age, who increasingly look upon their four years of college education from a consumerist perspective. I have little doubt that smaller schools would be only too ready to pick up big dollars from the corporate world, money that now flies into the coffers of the Harvards and Stanfords. Still, it is possible that precisely because small schools are not going to be the beneficiaries of this kind of soul-killing aid, they may be better placed to resist the splintering about which Egginton writes so persuasively.

Catholic schools in particular have the advantage of mission statements that stress the importance of the common good, and historic identities that stress the enduring value of community. Personhood rather than individualism, concern for the common good that prioritizes the needs of the poor over mere utilitarianism, and a commitment to the principle of subsidiarity together can put up staunch resistance to the neoliberal juggernaut, before which every person is simply a consumer. The twenty-eight Jesuit schools in the United States, for example, all prefer the word “formation” to “education”; they are inheritors of a tradition of extensive liberal-arts core curricula; and they like to stress that the paideia of the schools is care of the whole person (cura personalis) in the service of seeking magis—of going the extra mile in the search for moral and intellectual excellence. But there is little doubt that Alisdair MacIntyre’s warning in these pages (“The End of Education,” October 20, 2006) is real: the challenge and promise of American Catholic universities may very well not succeed. For much the same reasons as Egginton catalogues, MacIntyre believes that the liberal arts are in danger and that the leaders of the major Catholic universities “are for the most part hell-bent on imitating their prestigious secular counterparts.” If Harvard and Johns Hopkins or Georgetown and Notre Dame are in such a pickle, can the rest of us be far behind?

There is a solution, however. When the call is made to return to the values of community in order to overcome the social inequality that excessive individualism results in, it translates into a recall to the importance of undergraduate teaching. However enchanting arcane research and increasing academic specialization might be, it is not going to help preserve democracy in a truly free society. Egginton provokes us to the recognition that it is in an educational community that the values that promote the truly human will be nurtured. I do not know if he would go as far as Mark C. Taylor did in a 2009 New York Times op-ed, where he calls for the end of the university as we know it: abolishing permanent departments, transforming the traditional dissertation, imposing mandatory retirement, and abolishing tenure. But they would be at one in their belief that collaboration within the community of scholars is a sine qua non not only for a healthy university, but for a more alert and unified world. And where Taylor was simply being provocative, Egginton initiates an important and constructive inquiry into the contribution of our universities to the future of our society.

The Splintering of the American Mind

Identity Politics, Inequality, and Community on Today’s College Campuses

William Egginton

Bloomsbury, $28, 272 pp.