It’s no secret that museums and art galleries are under mounting pressure from activists, critics, artists, and the public to become more diverse. The results have mostly been uneven. But if two extraordinary shows that opened this spring and summer in New York City are any indication, change is coming. Mounted at two very different institutions, both devote necessary attention to artists and topics that have been willfully marginalized or simply ignored.

The Met’s Juan de Pareja, Afro-Hispanic Painter is a show in which context and rediscovery are everything. We already have some familiarity with the subject thanks to Diego Velázquez’s famous portrait, which was purchased by the Met in 1971 for the then record-setting amount of $5.5 million. (The work is a solid example of Velázquez’s mature style; the price seems modest compared to today’s delirious figures.)

Who was this handsome, dark-skinned man wearing a mustache and goatee? Pareja was an enslaved member of Velázquez’s household, his existence first documented in the mid-1630s. Born in Antequera in southern Spain, possibly to enslaved parents, Pareja was of sub-Saharan African heritage, and a morisco (Muslims forced by the Spanish monarchy to convert to Christianity after 1492).

It is very possible that Velázquez himself trained Pareja as a painter. We know that Velázquez brought him on a 1649 trip to Rome, where he traveled to acquire art for King Philip IV. This is when Pareja posed for the portrait, which was actually a “practice picture” for another portrait of Pope Innocent X. Shortly thereafter, Velázquez signed a document of manumission that would free Pareja at the end of a period of four years, on the condition that Pareja not attempt to escape or commit any criminal act.

The Met show includes most of Pareja’s surviving works, all painted during the last twenty years of his life. Was he an artist of originality, of substance? The problem with this question is that any artist next to Velázquez will seem competent at best. Of the many canvases in the show, two by Pareja stand out: The Calling of St. Matthew (1661) and Portrait of the Architect José Ratés (c. 1664). The first is Pareja’s most ambitious multi-figure composition. Here he fuses elements of Titian (the sumptuous tablecloth and Christ’s bright garments) and El Greco (the elongated figures seated at the table). Pareja also includes a self-portrait on the far left of the scene, placing himself among the sinners that accompany Matthew. Pareja’s portrait of Ratés likewise exhibits solid drawing, and a skilled handling of pigment. The earthy realism of Pareja’s corpulent subject recalls the influence of Caravaggio on seventeenth-century Spanish painting (including on the young Velázquez). In this sober work, Pareja distinguishes himself as a stylist with a vision all his own. His other paintings in the show, such as The Flight into Egypt (1658) and The Baptism of Christ (1667), are less convincing. Sentimental and drab, they betray Pareja’s occasionally insecure grasp of drawing and his awkward handling of paint.

The rest of the show features paintings by Spanish Baroque masters Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, Francisco de Zurbarán, and Claudio Coello, among others. There are also a handful of polychrome wood sculptures (including a magnificent rendering of the Black Sicilian Franciscan St. Benedict of Palermo, attributed to Montes de Oca), as well as eight canvases by Velázquez. Taken together, the works give visitors a sense of Pareja’s visual world, one in which Black people figured prominently in complex ways.

Our recognition of this fact owes much to the Harlem Renaissance scholar Arturo Alfonso Schomburg. An erudite Afro–Puerto Rican intellectual and collector (for whom a New York Public Library research center in Harlem is named), Schomburg pioneered research into Pareja more than a century ago. During the 1910s he patiently reconstructed the multiracial Spanish society of Pareja’s time, highlighting how people of African descent (moros and moriscos) had played important yet unrecognized parts. Schomburg’s utilization of the term “Afro-Hispanic”—more common today—was innovative, as was his promotion of Pareja’s identifiable paintings. (Art historian James A. Porter included Pareja in the earliest edition of his Modern Negro Art book.)

The Met show presents this material with clarity and elegance, never hitting the visitor with the “book on the wall” approach of many exhibitions. It constitutes a serious gesture toward thoughtful cultural equity. Still, it makes one wish the Met had had the courage to exhibit their holdings of modern Latin-American and contemporary Latinx art, instead of simply stressing diversity in the European past.

Located one mile up Fifth Avenue from the Met, El Museo del Barrio is doing just that. After a well-received series of recent exhibitions mostly consisting of loans from private collectors and other institutions (DOMESTICANX, an intergenerational multidisciplinary show, focused on the spirituality of the private sphere; Juan Francisco Elso: Por América examined the career of the late Cuban sculptor), El Museo del Barrio is now highlighting their permanent collection in a series of rotations from among their more than 8,500 holdings. Something Beautiful: Reframing La Colección groups an enormous number of these objects into a variety of innovative concepts and categories. There’s Taíno culture as a living resource; aspects of life in East Harlem and other barrios; printmaking and graphics as essential to both Puerto Rican and Nuyorican expression; abstraction, queer identities, and the body; and an individual retrospective of the late maestra Myrna Báez. The packed exhibition flows gracefully through the relatively modest space.

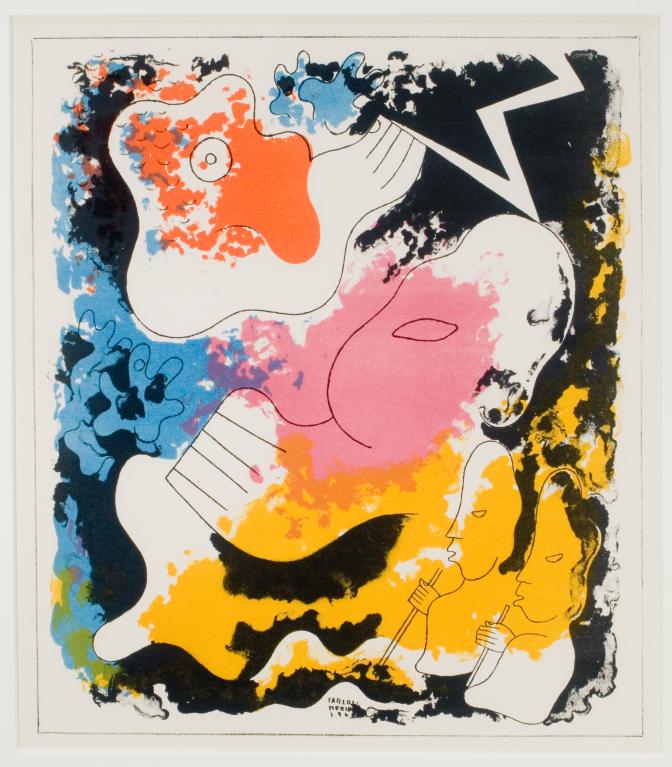

There are some extraordinary visual moments. Among the most interesting are Carlos Mérida’s portfolio of color lithographs depicting scenes from the Popol Vuh, a sacred Mayan text written in K’iche’, and several cases of Taíno artifacts. These sit alongside contemporary works like Juan Sánchez’s gorgeous painting The Most Cultural Thing You Can Do (1983), which fuses luscious colors and rich textures, pictographs, and a photo-collage of a tattooed Puerto Rican flag along with a text from the Young Lords about self-reliance and protection. Sánchez’s ability to create politically and spiritually charged works in a formally beautiful language has few parallels in contemporary art.

The exhibition is also strong in photography and printmaking. There are compelling images by Hiram Maristany, Perla de León, Máximo Colón, Héctor Méndez Caratini, Luis Carle, Julio Nazario, and Geandy Pavón, to name a few. The late ADÁL (Maldonado), a genuine Nuyorican Dadaist, blows us away with his blurry Out of Focus Nuyoricans series. Technical virtuosity and conceptual clarity is also evident in the linocuts and woodcuts of the Puerto Rican maestros Lorenzo Homar and Rafael Tufiño, who influenced Nuyorican printmakers whose works are also present. Worth a second look are José Alicea’s portfolio centered on a poem by Julia de Burgos, Antonio Martorell’s woodcuts with Ernesto Cardenal’s “Salmos,” and the funky and empowering graphics of the Taller Boricua artists. Folk art is also well represented, with paintings, textiles, and objects mounted alongside the work of trained artists. Particularly exquisite among these are four Mola cotton textiles by Guma artists from the 1970s.

El Museo boasts an eclectic collection of paintings, from the geometric abstractions of Carmen Herrera, Fanny Sanín, and César Paternosto, to the expressive figuration of Nitza Tufiño, Jorge Soto, and Beatriz González. The section dedicated to the late painter and printmaker Myrna Báez (1931–2018) is simply breathtaking, making this viewer wish for a major retrospective of her work, long overdue. Five prints and two paintings by Báez present her poetic realism, where the human body appears both sharp and fluid and the landscape pulsates with movement.

Rounding things out are two works commissioned specifically for this reframing of El Museo’s collection. Glendalys Medina’s sculptural, site-specific intervention, Cohoba, brings viewers into the ceremony that lies at the spiritual center of Taíno life. Like a small, darkened chapel built to hold saintly relics, Medina’s creation grants comfort and serenity to the visitor. By way of contrast, Maria Gaspar’s Force of Things is a minimalist tour de force of sculpture, painting, and video. It commemorates the demolition of the largest single-site prison in the country, Chicago’s Cook County Department of Corrections. In a cold, white space, visitors are confronted with actual jail debris salvaged from the site—penal objects rarely visible beyond carceral spaces. Gaspar’s open-ended arrangements enable viewers to experience, if only for a moment, the same emptiness, brokenness, and despair that prisons and jails regularly inflict on their inhabitants.

Aesthetics have always been inseparable from politics, and the curators of Something Beautiful make this refreshingly palpable. They write: “Unlike the majority of mainstream art museum collections, which continue to center Eurocentric values and art historical canons despite efforts to diversify, our collection is grounded in a decolonial project.” That’s been true since El Museo’s founding in 1969, when it emerged from and for the Nuyorican community. Since then, it has expanded to embrace the city’s many other Latino communities (Chicano, Dominican, Cuban, Central and South American), as well as Latin America, without forsaking its Nuyorican origins. The reinstallation of the collection is therefore much more than a simple updating of a single institution. With its focus on hybridity—that paradoxical, lifegiving fusion of Indigenous, African, and Spanish cultures—it’s a profound statement of the complexity of Latinx identity as a whole. It will surely resonate with Latinx communities across the United States and beyond.

Juan de Pareja, Afro-Hispanic Painter, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, through July 16

Something Beautiful: Reframing La Colección, El Museo del Barrio, through March 2024