Ken Burns’s new documentary, Country Music, premieres on PBS on September 15. Over the course of eight episodes spanning more than sixteen hours, the film traces the long and complex development of the genre—from the early days of “hillbilly music” in the 1920s and 30s, through the development of the polished Nashville Sound of the 1960s, up to the emergence of the roots-oriented artists of the 1980s and 90s. A monumental project that took eight years to complete, Country Music is based on 175 hours of interviews with musical legends like Loretta Lynn, Kris Kristofferson, and Merle Haggard, among many others.

Burns is an award-winning documentarian, known for his iconic films like The Civil War, Jazz, Baseball, The Roosevelts, and Vietnam. He spoke with Cole Stangler for Commonweal about Country Music, the art of storytelling, American history, and the current political moment. This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Cole Stangler: Thanks so much for taking the time to do this. I just finished the documentary over the weekend.

Ken Burns: Thanks. I appreciate you watching the whole thing.

CS: Of course! I couldn’t possibly interview you without watching the whole thing.

KB: You’d be surprised by how many people say: “Oh I watched a little bit of the first episode and then skipped to the end.” And it’s like, come on.

CS: No, it’s important to watch or read things before you interview people about them. To start then, how did you come across this topic? Why country music?

KB: Well, it’s been a topic in the intellectual sense of being on a couple of my lists from the nineties and beyond. But it hadn’t really dropped down into my heart. And I had a friend in late 2010 who said, “What about country music?” And the fireworks went off. I kind of got down on my knees and proposed Country Music then. Eight and a half years later, this is what we’ve got.

I think after we make a film, we sort of backfill it with a lot of intellectual stuff. But at the end of the day, I’m a storyteller. I happen to work in American history. I’ve got a lot of interest in telling complicated and intertwined and good stories in American history, and fortunately work with really talented people, particularly Dayton Duncan, the co-producer and writer of the series, and Julie Dunfrey. So this is a labor of love. And I think it’s a hugely important story to tell.

For us, I’ve always said, since my very first film forty years ago, that I was uninterested in excavating the dry dates and facts and events of the past, as if there was some quiz awaiting you. The last time I checked, that’s called homework. There is no quiz. But I am interested in an emotional archaeology. Not interested in sentimentality or nostalgia, but interested in an emotional archaeology. And I can’t think of a film I’ve worked on that has more powerful and more universal human emotions than this project.

CS: So obviously, you mentioned your films are dealing with American history, grappling with themes that are very American. By taking on a project like this, that implies there’s something important about country music’s connection to American identity or to something about the United States. What’s behind it? You’re not just telling a story about the genre of music, this is revealing something else.

KB: First, I think we have to realize that commerce and convenience categorizes almost everything to its detriment so that we end up with kind of isolated or siloed sense of something. It’s always one dimensional and kind of superficial and what our deep dive documentaries permit us to do, I hope, is liberate these topics from the tyranny of that imprisonment and to remind people of the interconnectedness of all of the subjects we’ve tackled.

In fact, one other way might be to flip it on its head and say, “I make the same film over and over again, each one asking a deceptively simple question: ‘Who are we?’” And while you never answer the question, you deepen the exploration of it. You know people are fond of saying, “History repeats itself.” It does not. We say the lovely poetic phrase: “We’re condemned to repeat what we don’t remember.” It’s lovely and I understand the impulse for it, but it’s just not true.

Ecclesiastes said: “What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again.” There’s nothing new under the sun. Which seems to suggest that human nature is the same. And it superimposes itself—good and bad and everything in between—on the chaos of events. So we do perceive themes and motifs and echoes. Mark Twain is supposed to have said: “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes.” And whenever we finish a project, we’re always surprised by how much it rhymes. But the emphasis is, when we finish a project. Because we’re not interested in sort of putting up neon signs that say: “Hey, isn’t this so much like today?” Whether it’s the Vietnam War or Country Music or The Roosevelts or The Civil War or anything that we’ve done. But it always is about today because perhaps Ecclesiastes is absolutely right, there’s nothing new under the sun.

In my work, in the parochial, if you will, area of American history—I’m a filmmaker, I’m not a historian, I’m a filmmaker—you begin to see recurring themes about freedom, and the great tension inherent in that in the American story. That is to say, the tension between our collective freedom—what we need—and a personal freedom—what I want. And they’re often very much in opposition or in conflict with one another.

Race is, of course, a central theme in America, which is dealt with in almost every film I’ve done. You don’t necessarily go out looking for it, but it’s nearly always there, in large measure, because we know when we were founded, and what our guiding catechism is, the second sentence of the Declaration. The guy who wrote “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal” owned more than two-hundred human beings in his lifetime and never saw the hypocrisy, never saw the contradiction, and never saw fit in his lifetime to free any of those human beings. Also, we have gender issues, we have geographical tensions, we have creative ones, we have business ones. All of those rear their heads in various ways throughout the films that we’ve done, and none more so, I believe, than in Country Music.

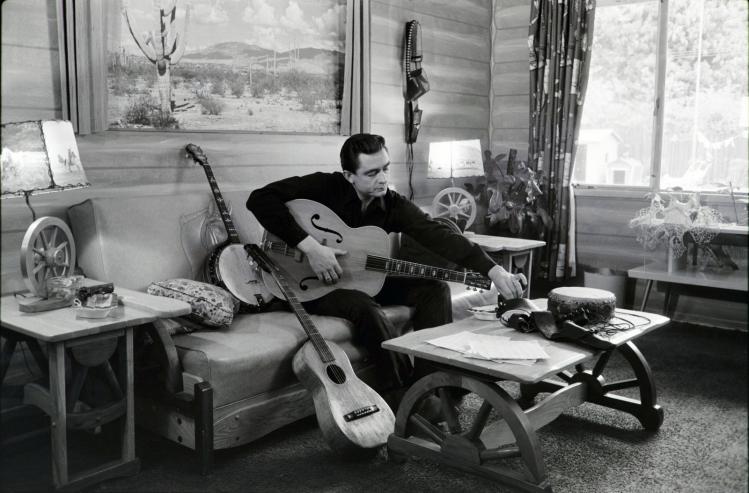

The conventional wisdom suggests that country music is merely this white, conservative force. In fact, it is like all other forms of music, American music, connected to each other. It is one of the parents of rock and roll, it has always been connected to jazz, and rhythm and blues, and pop and rock and classical in ways that I think people will find surprising. Particularly when you consider, say, the top five people in the pantheon of early country-music stars: A. P. Carter and the Carter Family, Jimmie Rodgers, Bill Monroe, Hank Williams, and Johnny Cash. Four out of those five all had an African-American mentor, a specific person they referred to—Lesley Riddle in the case of A. P. Carter, Arnold Schultz in the case of Bill Monroe, Rufus “Tee Tot” Payne in the case of Hank Williams, and Gus Cannon in the case of Johnny Cash—who actually took their chops from here and took it to way up there, which puts them in the Pantheon. The only person left out is Jimmie Rodgers, whose entire influence is from the blues and from listening to the black train crews in southern Mississippi work the track, but also work on the soundtrack of Jimmie Rodgers’s mind, and that’s a pretty startling thing to find. That the people you put in Mount Rushmore all had an African-American influence.

Then you think about the two seminal instruments of country music: the fiddle clearly comes from Europe and the British Isles, but the banjo comes from Africa. So this is a hugely complex alloy, this music called country music. It isn’t one thing and it never has been. The big bang of country’s music’s creation is supposed to be in Bristol, Tennessee, in the summer of 1927, when Ralph Peer records in different sessions, first the Carter Family, and then, a week later, Jimmie Rodgers. Jimmie Rodgers, who represents the rogue, the scamp, the Saturday night of country music and all of American music and culture, and the Carter Family which represents the Sunday morning, of home and values and family and church and all that sort of stuff. And then, it went off almost in this big huge spree, acquiring cowboy music and Western swing and the Bakersfield Sound, and then the smoother Nashville Sound, and the even smoother Countrypolitan. And string band music itself was evolving into lots of different subgenres, including the most spectacular thing—not dissimilar from bebop’s contribution to jazz—which is bluegrass.

It begins an alloy and it ends up an even stronger alloy. And I think this is the great mistake we make in American life, which is, we tend to—because of commerce and convenience—categorize things and then to make them purely superficial so we don’t understand their diversity. We always think America is one thing, that “if I just pull out this one thing, we’ll be stronger,” when in fact, that’s what weakens the alloy. You know, you take out the iron from steel, and you’ve got a much less strong, much more brittle thing.

I have had the great privilege and—I’m sorry, I’ll soliloquize for a second, then I’ll shut up.

CS: Go ahead!

KB: I’ve spent my entire professional life occupying this pretty unique space between the lowercase two-letter plural pronoun “us” and its capitalized equivalent, “the U.S.” All of the intimacy and warmth of “us,” plus “we” and “our,” but also the breadth and the majesty and the complexity and the contradictions and the controversy of the U.S. And that’s a wonderful thing.

It occurred to me—as I’ve been thinking about this and speaking to groups all around the country about the Country Music series—that we tend to establish, no matter what everybody says, a kind of binary, oppositional, dialectal kind of force, but there’s no “them.” The “us” that I’m talking about has no “them” to it. There is not a corresponding other. And that’s what we tend to create. What I’ve tried to do in my work, what I think I’ve tried to do—it’s not conscious but looking back, I sort of feel that the collective message, if you will, is that there’s no “them.” There’s only “us.” It’s harder to get your head around than it sounds. It’s not a slogan, it’s not some kumbaya sentimental nostalgic thing. It’s just, there is no “them.” It’s a human experiment. And we’re all in it, as someone says in Country Music, we’re all in it together.

I just think, isn’t it interesting that when you say country music, more often than not, you get a superficial response: “Oh, this is good old boys and pick-up trucks and hound dogs and six packs of beer”? And I don’t mean to say that that isn’t a part of it, but it is a tiny, insignificant part of country music. It’s dealing with two big themes, two four-letter words, that we’d rather not deal with: love and loss. And I’m interested in those two things.

If you think about the best of country music today, it is dealing with these universal experiences that every single one of us, whether you’re a classical-music fan or a rock fan or an opera fan or a folk fan or whatever, you’re dealing with. Just like opera is dealing with. Just like rock is dealing with. Just like rhythm and blues is dealing with.

CS: There’s a lot to…

KB: I’m so sorry!

CS: That’s ok, it’s interesting. I think one of the things you really hit on there, among other points, is this idea of the interconnectedness of the kind of music that the film is digging into. I thought that was one of the things that really spoke to me, and one of the things that really comes across in the series, is how intimately tied country music, as a genre, what’s known as country music today and what we call country music, is so closely tied to these other forms of music.

KB: Yeah. Well, I tried to describe it and I think it’s a fairly imprecise analogy to a kind of molecule. Where we think you have distinct atoms of country music and atoms of the blues, but actually American music is a complex molecule in which country music is forever bonded and connected to the blues, to jazz, to rhythm and blues, to folk, to pop and even to classical, and all of those other forms are themselves connected. I mean, all you have to do is look at the musical roots.

Look at Bob Dylan and what he did. Look at The Beatles, you’ve got Paul McCartney drawn, of course, to the ballads of Marty Robbins. You’ve got George Harrison, of course, listening to the blues of Jimmie Rodgers and the guitar playing, the jazz-influenced guitar playing of Chet Atkins. And you’ve got, of course, the heartache of Hank Williams fusing John Lennon’s early influence. And you’ve got Gene Autry, the singing cowboy, as the primary musical force in Ringo Starr’s life, or at least, his decision to choose music. That’s just one band.

And it goes both ways. As you saw, when Ray Charles is given creative control of an album for the first time, what does he choose? To the surprise of his own people, Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music. In which he plays Hank Williams, he knocks out of the park Hank Williams’s “Hey Good Lookin,’” but he also takes the number-one song of the summer of 1962, “I Can’t Stop Lovin’ You,” which is Don Gibson’s country song.

You realize that there are no borders. That somehow that station you think is only being listened to by white people, or that station which is only being listened to by black people, just isn’t true. If you look at the birth of rock and roll, which occurs arguably in 1954 in Memphis, with Sun Records and Sam Philips, you’ve got two white boys, Elvis Presley and Johnny Cash, who’ve been listening to gospel—both black and white—to hillbilly music and to rhythm and blues. They bring all of that together and the explosion, the fusion that takes place, is rock and roll. Even though you can listen to, a decade before, the Maddox Brothers and Rose’s “Step it Up and Go,” which sounds like Bill Haley’s “Rock Around the Clock,” as Marty Stuart demonstrates so aptly in the film. So there’s just no borders, there’s no passport required.

And yet, as I keep saying, commerce and convenience, particularly in a time when we’re overwhelmed with information, suggest that these easy, simplistic categorizations are helpful, when in fact, all they do is imprison these forms into their own rigid groups, when the artists just don’t recognize these boundaries. Bob Dylan is clearly the biggest example of that.

CS: This film comes in, I think, at sixteen hours long. Like your other films, a very long project. A simple question: Why make movies that are so long? Is that something you’re thinking about as you’re telling the story? Presumably it changes the audience?

KB: It takes sixteen hours and twenty minutes. I suggest that any book that you’ve got on your shelf will probably take you that long to read. Complex stories require some time. All meaning accrues in duration. The work that you’re proudest of, the relationships you care about the most, have benefitted from your sustained attention.

I was told by the critics for The Civil War, Baseball, and Jazz, that no one would look at it, because we’re in the MTV generation of quick-cutting two-and-a-half minute music videos, and what am I doing lingering on a single photograph for thirty seconds. And yet, you know, The Civil War is still the highest-rated program in PBS history. And then after that, it was no longer MTV for World War II and The National Parks, it was the fact that no one would watch these long-form things because of YouTube and some kitten playing with a ball of yarn for two minutes. And yeah, all of those are important, MTV videos are important and kittens playing with balls of yarn are important. But the stuff that has meaning, the stuff that you seek out, particularly now with this tsunami wave of information breaking over our heads, we’re not only starved for meaning—which accrues in duration—but we’re starved for curation.

So it was interesting, by the time The Roosevelts came out in 2014, nobody was saying that no one was gonna watch it anymore. It was like, “Oh yeah, we’re desperate to watch something this long.” That was true of The Roosevelts, that’s true of Vietnam and I assume that it’ll be true of Country Music, because we look for that kind of curation and we require complexity in our stuff, and it still does not exclude that music video or that kitten and that’s important. These are not mutually exclusive things. There’s no “them,” right? There’s no other.

I needed the time to tell it. And we don’t say: “Okay, we’re starting off at sixteen-and-a-half hours or eighteen hours for Vietnam.” You think “well, maybe it’ll be this” and you listen to the material in it, and it tells you what it means, and what was going to be six episodes of Country turned into seven before we got off the paper. Then it turned into eight in the early days of editing. Vietnam started off as seven and then it was very quickly on paper, going to be eight, and then we realized, the material we had warranted nine and ten. You just figure out how you move the goalposts: How do you make sure that each episode has its own integrity in addition to fitting it into the whole?

But this is not an additive process. It seems like, if you’re building a building, it’s additive, and it is, but you still have scaffolding and falsework that has to be removed. I think of this more as subtractive. I live in New Hampshire and we make maple syrup and it takes forty gallons of fat to make one gallon of maple syrup, which is a pretty good equivalent. We collected a thousand hours of footage, 175 hours of interviews from 101 people, 20 of whom have died, 41 of whom are in the Country Music Hall of Fame. We looked at 100,000 photographs, we used 3,400 of them in our final film. And from tens of thousands of pieces of music we listened to, we have 584 music cues. All of it is reductive. All of it is kind of a distillation process.

CS: When we’re thinking about the kinds of ideas that people have about country music, these kinds of categories that people put it into, the kinds of clichés about it, there’s this notion—and this was true for myself, growing up, when I was younger—this idea that country music, politically, is right-wing music. It was after 9/11 with the Toby Keith pro-Iraq War songs and you certainly have artists that are right-leaning, but you also have people on the other side of the political spectrum, Steve Earle, Willie Nelson, among many others.

KB: Woody Guthrie, The Dixie Chicks.

CS: Of course!

KB: And people who realize all of these things don’t matter. I mean, if Toby Keith can play, he can play. And what, does he not experience heartache because he’s right-wing as opposed to somebody who might be more sympathetic to your or my particular views? No, that’s one of the “us” and “them” things. And this is a more modern manifestation anyway. Our film ends before 9/11.

CS: Sure, I mean, to take another example then—and this is more complicated—but the Merle Haggard song “Okie from Muskogee” which, I would actually say, is maybe less explicit politically than the Toby Keith song is, because as you mention in the film as well, it’s a very nuanced song. And it’s not exactly…

KB: It got appropriated by the counter-counterculture. And he then fell into the trap for a while, but that doesn’t represent Merle Haggard’s extraordinary career or contributions to it. It’s one sort of story within a much more interesting and complex story and that’s what we do.

I mean, look, we might as well get right to the point right now. The number-one country song of all time, the number-one single of all time, is Lil Nas X’s “Old Town Road.” And he is a black, gay rapper. At this point, I can drop the mic, right?

The binary attempts, which are the products of our computer age and our journalistic age, the attempts to set up or to accentuate a simple, binary conflict doesn’t hold a candle to what he represents or to what art represents. As Wynton Marsalis says in the film, we all have an ethnic heritage, but we have a human heritage that’s much more important. Art tells the tale of us coming together, and that’s all I’m interested in.

In my Jazz series, Wynton said something that’s stuck with me for more than twenty-five years. He said: “Sometimes a thing and the opposite of a thing are true at the same time.” I mean, that’s what art is able to actually understand in a way that our sort of normal day-to-day binary responses can’t do. We always need it to be one thing or the other. Merle Haggard can only be “Okie from Muskogee.”

Lil Nas X is only—I mean, how come Billboard dropped him? Who the fuck cares whether Billboard dropped him from the country charts? What happened? Everybody got it. Everybody got it. It’s not dissimilar to DeFord Bailey, a diminutive black harmonica player, being one of the most popular people on the unseen, only-heard Grand Ole Opry in its early days or Ray Charles crossing over to pick up this white music, supposedly, to do his first album that he wanted to do. That meant he’s spending as much time listening to country music as he is listening to R&B. He’s an R&B singer.

To me, that’s the key to it all. There’s the reconciliation. There’s the redemption that Roseanne [Cash] says that her dad Johnny was seeking every night on stage. The ability to hold, as she put it, two contradictory things at once. He could be against the war in Vietnam and go support the troops, right? He could be for this and against whatever. He worked out all of that stuff, as she said, on the stage, which is, I think, a beautiful description of the artist’s dilemma—the necessity to hold opposing views without making it the simple good guy, bad guy thing that we do, the binary, the red state-blue state, young-old, rich-poor, gay-straight, male-female, left-right, whatever it is.

CS: So this film ends in 1996 and covers Johnny Cash’s death in 2003. You’re making films about things that have already happened…

KB: That’s what history is.

CS: Of course, but as a filmmaker who’s chronicled these really important themes and moments in American history, and stories, you know, are you ever thinking about today? When you look at the political context today, and you look at Donald Trump…

KB: No, not when we’re making them. I used to start my stump speech about the Vietnam War film, which came out two years ago (I was promoting it in the summer of 2017, you know where we were then and what we’d been through): What if I told you I spent ten-and-a-half years—that’s how long Vietnam took—working on a film about mass demonstrations taking place all across the country against the current administration; about a White House in disarray, obsessed with leaks; about a president who’s certain the media was making up stories about him; about huge document drops of stolen, classified material into the public sphere that destabilized the political conversation; about asymmetrical warfare that confounded the mighty might of the US military; and about accusations that a political party reached out to a foreign power during the time of a national election to influence that election? You would say, you’ve been making a film about the last year and a half. When in fact, all of those things were true about Vietnam when I began the film in December of 2006. When we locked the picture, meaning no more editorial changes, [it was] in December 2015, a month before the Iowa caucuses out of which Donald Trump was not supposed to emerge.

My business is to keep my head down—it took eight-and-a-half years for Country Music, because this is a Russian novel of a story over many generations—but I know I will not be able to convince anyone with regards to the startling feminist, or proto-feminist dimensions to Country Music that we didn’t do this post–MeToo movement. We were done with this thing by the time the MeToo movement came out. And yet in episode after episode after episode, you have women dealing with groping executives, or women dealing with unhappy marriages, or Loretta Lynn singing, well before anyone in rock or folk did, “don’t come home a-drinkin’ with lovin’ on your mind.” You know, which is a startling thing to say in the mid-sixties.

So I think my job is—maybe after the fact, speaking to you, we can sort of pull together these themes—but we just gotta imagine the story and that’s it. And good storytelling, good history, is always evergreen. Like, if you focus on a contemporary issue, it has a kind of transience that’s similar to skywriting, it looks pretty clear—“Surrender Dorothy”—but in a couple of seconds, that stuff, that smoke is dissipated by the first zephyr, the first breeze.

I could take any of the films I’ve made and do the exact same thing I did with Vietnam or Country. I’ll tell you about a film, it came out in 2011—what if I told you I’d been working for several years about a single-issue political campaign that metastasized with horrible, unintended consequences. It was about the demonization of recent immigrant groups in the United States, it was about a presidential campaign filled with smears at the lowest and basest level, and it was about a whole group of people who felt they lost control of their country and wanted to take it back? In 2011, you go, man it’s the Tea Party, it’s Karl Rove, whatever. This is Prohibition. You go, “What? What? Prohibition is gangsters and flappers,” and I go, that’s an important part and you’ll see them, but what’s more interesting is that single-issue political campaign that metastasized: and these are all the same tropes in American history.

CS: I guess then, if you want to continue on that logic, the implication is what’s going on today—Donald Trump and the Trump administration—is that a continuation of some of the trends we’ve seen before, like nativism, or is it something new?

KB: Everything is new and everything is also the same. There’s nothing new under the sun. There are new manifestations of old things, which have been manifesting in the United States since the very beginning. I’m working on a film about the American Revolution right now. All of this stuff is there: you have the nativism, the Know-Nothings in the 1830s and 1840s. You have the Civil War, which is really, that’s where things are breaking down.

We’re making a film on the United States and the Holocaust. And the National Socialists studied our exclusionary laws, you know. We also had passed these restrictive immigration rules. They came and studied our Jim Crow laws to figure out how to exclude Jews from their political process and stuck around for eugenics and then of course perfected it in the most horrific fashion ever known to man. So this stuff is always there.

You look at one of the great historians, Richard Hofstadter, who wrote The Paranoid Style in American Politics. I don’t need to comment on Donald Trump because it just is. It’s part of an American manifestation.

So interesting that it comes after Barack Obama. I’ve dealt with race in almost all my films, and I’ve been so vilified by critics for creating a race-based lens through which I see things. I don’t. I just investigate stuff and race is there. Even my friends [would] say, “Will you shut up about race?” When Barack Obama was inaugurated on January 20, 2009, they said, “Now, will you stop talking about race? We’re post-racial.” And I held up The Onion whose headline that day was “Black Man Given Worst Job in Nation.” And I said: “Just watch what happens.” And to their credit, those friends who were exasperated with me have come back and apologized.

One of the last comments in our Civil War series that came out nearly thirty years ago (we finished it thirty years ago last month) is [the historian] Barbara Fields, who says “the Civil War is still going on, it’s still being fought and regrettably, it could still be lost.” And that thing went viral two years and a month ago when Charlottesville happened. How does an old film with squeaky violins that’s supposed to be an apology for the Old South begin with an episode on the reality of slavery and end with Barbara Fields talking about that? If that’s not how it always is, and I’m sorry to say, how it probably always will be?

We have greed and we have generosity. They coexist not between people and between eras, but sometimes within the same person. And those kinds of psychological divisions: look at The Roosevelts series or look at Hank Williams—“I got a Hot Rod Ford and a two-dollar bill and I know a place right over the hill,” from “Hey Good Lookin,” some of the greatest haiku poetry ever. About falling in love, he also writes “You hear that lonesome whippoorwill, he sounds too blue to fly, the midnight train is whining low, I’m so lonesome I could cry.” I mean, when you take the art of music—which is the only art form that’s invisible, as Wynton [Marsalis] says in this film—and you add it to poetry, the distillation of our language, the purest distillation of language, watch out. And that’s true of almost every musical form. We just happened to, in this case, focus on country. It’s a pretty powerful, emotional archeology we’re attempting.

CS: Thanks so much for your time.

KB: Thank you.