March 29 was a Good Friday indeed in New Jersey: that morning, a federal judge in Trenton issued an order temporarily curtailing the use of a strange and controversial ballot design that has been a fixture of the state’s electoral landscape for decades. The significance of this decision might not be immediately apparent to those not steeped in the minutiae of New Jersey politics, but the seemingly minor change that it brings about—still provisional for now, as the underlying litigation continues to wend its way through the courts—has already dealt a historic blow to the power of the state’s notoriously entrenched party machines.

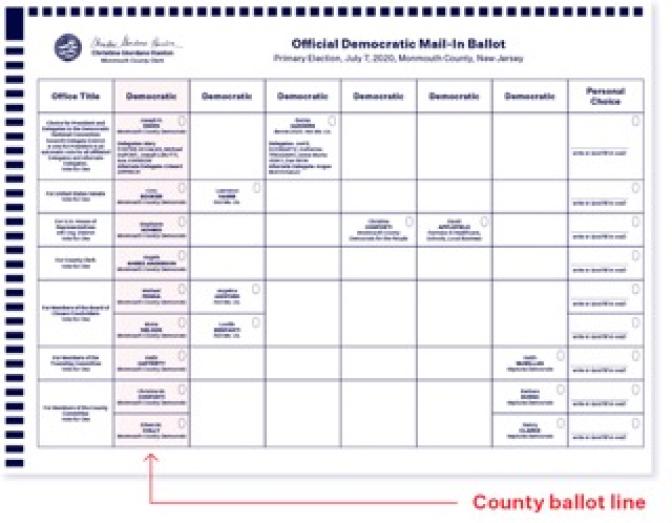

As a lifelong resident, I’m allowed to point out that the Garden State can be an odd place. But while some of its quirks are harmless or even charming, its unusual primary-election ballots are a less than amusing peculiarity. Virtually everywhere else in the United States, as well as in two of New Jersey’s own twenty-one counties, the names of candidates in party primaries are grouped together on the ballot based on the position being sought—the so-called “office-block” format. In the other nineteen counties, however, candidates who receive the official endorsement of the local Democratic or Republican Party are listed in a single prominently positioned column or row known as the “county line.” Other contenders are scattered across a large grid, seemingly at random, and can end up relegated to the bottom or far edge of the page in what some have dubbed “Ballot Siberia.”

The story of how New Jersey ended up using this ballot design in the first place is complicated, but the political implications have been profound. Because the county line usually includes a full slate of candidates for every position up for election, and because it receives prime placement near the top or left-hand margin, it is almost always the most visually arresting feature of a primary ballot. Relatively little-known candidates for lesser offices who receive a party endorsement benefit from being conspicuously associated with high-profile incumbents: I might not know anything about the person running for dogcatcher, but the fact that their name is listed under the president’s must count for something, right?

Critics have long claimed that this setup tilts the playing field by steering voters’ attention toward candidates preferred by the party establishments—a claim that has largely been vindicated by researchers who have studied the electoral effects of “the line.” According to an analysis by Julia Sass Rubin of Rutgers University’s Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy, those who garner endorsements from their local party branches in some counties but not others perform, on average, a whopping 38 percentage points better when they appear on the line than when they don’t.

In 2020, a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of county lines was filed by a group of Democratic congressional candidates who alleged that the ballot design had put their campaigns at an unfair disadvantage. But while that case has languished in the years since, a more recent legal blitzkrieg against the line, launched by Congressman Andy Kim, has met with stunning success.

Kim, who has represented a House district covering portions of southern and central New Jersey since 2019, announced a primary run against fellow Democrat and longtime U.S. senator Bob Menendez last fall, after federal prosecutors unveiled bribery and corruption charges against Menendez. Shortly thereafter, he was joined in the race by First Lady of New Jersey Tammy Murphy, who has never held elected office.

Within weeks, Murphy had won endorsements from a host of top party leaders, including six of New Jersey’s eight other Democratic U.S. representatives, and ended up nabbing the line in seven counties. While Kim secured the line in several counties too, he mostly did so in places with a relatively open and consultative endorsement process; Murphy, by contrast, prevailed in counties where these decisions are made in the proverbial back room.

Media figures began to point out that the situation smacked of political nepotism, as it appeared that Gov. Phil Murphy might be using his position and influence to give his wife a leg up in the race. New York Times political reporters Nick Corasaniti and Tracey Tully observed that “six of the seven county leaders who endorsed Ms. Murphy within three days of her entry in the race… have financial incentives to please the governor, who controls a budget that last year exceeded $54 billion.”

In February, Andy Kim and two other congressional candidates lodged a suit in federal court to have the county lines declared unconstitutional, repeating in their complaint many of the allegations made in the earlier case from 2020. While acknowledging that he had benefitted from it in his past campaigns for the House, Kim claimed that it was only in this Senate race that he became fully aware of how “fundamentally unjust and undemocratic” the line really is. On March 24, Palm Sunday, Murphy abruptly quit the race. Ostensibly, this was to avoid a “very divisive and negative campaign,” but at the time, I suspected the move was strategic: by ending her campaign, she appeared to render Kim’s lawsuit irrelevant, ensuring the lines could live to see another day. Perhaps the party machine had convinced her to take one for the team.

If this was really the plan, though, it didn’t work out as intended. In part because the other candidates who had joined Kim in the suit were still denied the line in their own races, District Court Judge Zahid Quraishi declined to throw out the case, and instead issued a preliminary injunction blocking use of county lines in the June primary. (He later clarified that his decision applies only to the Democratic side, meaning that GOP ballots will remain unchanged for now.) While the lines have not yet been permanently struck down, Quraishi’s order strongly suggests that he believes they should eventually be thrown out for good.

It is hard to overstate the import of this decision. New Jersey is a state famous for being home to legendary political bosses like Jersey City Mayor Frank Hague, who died a millionaire in the 1950s despite never having earned more than a few thousand dollars a year in legitimate income. David Wildstein, who pled guilty in 2017 to involvement in the bizarre “Bridgegate” plot but who has since managed a second act as an astute commentator on state and local affairs, described Quraishi’s action as “one of the biggest things that’s ever happened in New Jersey politics.”

Some elements within the Democratic establishment are now taking the fight to the Third Circuit Court of Appeals, with one county party even retaining Barack Obama’s former solicitor general Neal Katyal to help them in their last-ditch effort to preserve the status quo. But others have chosen to surrender peacefully. A surprising number of current officeholders have now come out in favor of abandoning the old regime, suggesting that the lines may indeed be done for one way or another.

My own former congressman Tom Malinowski wrote an op-ed candidly explaining how the lines create perverse incentives, including and perhaps especially within his own Democratic Party. Rather than focusing on addressing the concerns of voters, expanding the party’s base, or investing in campaigns in swing districts, elected officials and other party leaders have instead become fixated on currying favor with those above them and doling out spoils to those below. Malinowski describes how his time in office opened his eyes to the reality that “the main function of the Democratic Party organization in New Jersey is not to help Democrats win the hard races. It is to decide which Democrats are allowed to win the easy ones.”

It is no exaggeration to say that the Garden State has become more democratic (lowercase “d”) with the apparent demise of the county lines. Americans rightly scoff at the absurdity of sham elections in one-party states where the winners are chosen in advance, but our own elections, even in the absence of outright fraud or intimidation, are not always as “free and fair” as we might like to imagine. From that perspective, anything that moves us closer to realizing our democratic ideals should be celebrated as a win.

At the same time, we should recognize just how low the bar is right now, and how dysfunctional democracy in New Jersey—and in the United States more generally—is likely to remain for the foreseeable future. The overturning of the line might make it easier to challenge the state’s party establishments, but there is no reason to think it has become any easier to challenge the major parties themselves. Despite polling that shows a majority of Americans are dissatisfied with the two-party system (and with their two main choices for president this November), a combination of winner-take-all elections and restrictive ballot-access laws means that it is impossible for minor parties to gain a foothold almost anywhere in the United States, no matter what the ballots look like.

A growing number of good-government reformers are calling attention to the lack of genuine political competition as one of the fundamental causes of a range of serious problems, including partisan gridlock and widespread disillusionment among the electorate. The zero-sum nature of our politics is a structural issue that cannot be fixed through appeals to civility or decorum, important as these may be.

Organizations like the ProRep Coalition, which advocates for proportional representation in the state of California, are persuasively arguing that America would benefit from becoming a multiparty democracy of the sort that exists in many other countries. If seats in Congress or state legislatures were allocated to different political parties in proportion to the number of votes they receive, rather than the number of geographic districts in which they win the most support, more people might come to believe that voting is worthwhile and that their interests and perspectives can be meaningfully represented in government. As it turns out, nations with proportional representation usually have much higher rates of voter turnout than the United States. And because geography is less important under such a system, the incentive for gerrymandering is reduced, if not eliminated entirely.

Enacting such root-and-branch reforms will not be easy. In recent times, the Democratic and Republican Parties have strongly resisted any measures that threaten their institutional prerogatives, whether abolition of the county line in New Jersey or the passage of ranked-choice voting in places like Alaska and Maine. But the long struggle against the county line that culminated this past Good Friday should offer hope, since it illustrates how transformational change can seem unattainable until the moment it is suddenly attained. Yet much more transformation is still needed. It may be the end of the line in New Jersey, but the reinvigoration of democracy both here and everywhere else in the United States is only just getting started.