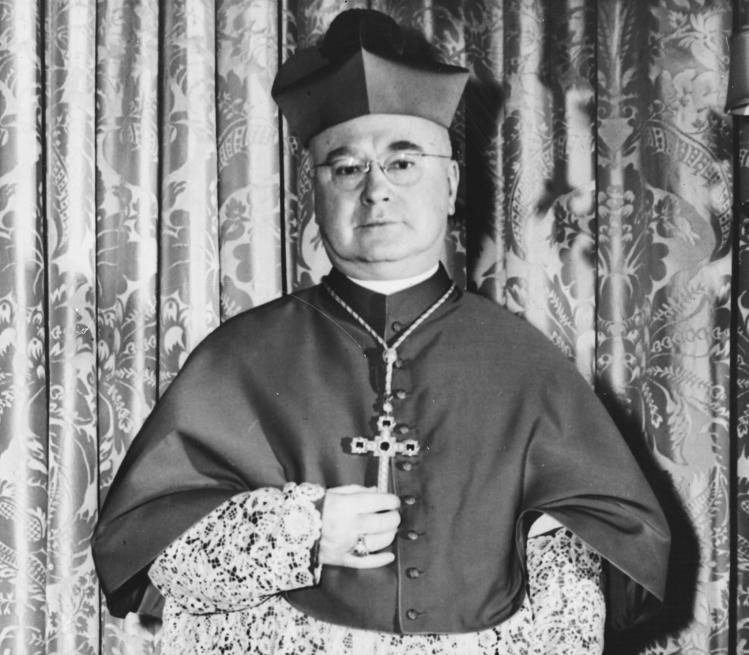

I recently spent too many hours plowing through John Cooney’s four-hundred-page 1984 biography, The American Pope: The Life and Times of Francis Cardinal Spellman. Spellman was archbishop of New York from 1939 to 1967. He was notorious for his autocratic style and the power he exerted both inside and outside the Church. He was also known for his political conservatism, rabid anticommunism, American jingoism, unstinting support for the war in Vietnam, love of pomp, and financial acumen. He seems to have been almost a caricature of what Protestants long feared about Catholic clerical authoritarianism.

During his nearly thirty years of near dictatorial rule in New York, the cardinal’s residence became known as “The Powerhouse.” He raised and spent hundreds of millions on new schools, churches, and hospitals. Mayors, governors, senators, and presidents paid homage. Spellman counted J. Edgar Hoover and Roy Cohn as friends and collaborators. He was an outspoken defender of Sen. Joseph McCarthy’s red-baiting, and lent his support to Richard Nixon rather than John F. Kennedy in 1960. Although he was conventionally pious, he seems to have thought of himself more as the chief executive of a multimillion-dollar enterprise than as a spiritual leader. “Few people thought of him as a priest at all,” according to the novelist and critic Wilfrid Sheed. Although Spellman apparently had a softer side in private, “he really was quite the bogeyman in public.”

Spellman, a Massachusetts native and 1916 graduate of Rome’s North American College, had little interest in theology, and resisted Vatican II’s reforms. “I hire theologians,” he once said, dismissively. He campaigned to ban movies, such as Roberto Rossellini’s The Miracle, that he judged blasphemous or obscene. When an article in Commonweal criticized such censorship, Spellman got the author fired from his teaching job at the University of Notre Dame. “Error has no rights” was his firm belief. In 1949 he used seminarians to break a strike by the diocesan’s cemetery workers, falsely claiming their union was infiltrated by Communists. His famous feud with Bishop Fulton J. Sheen, once the most popular priest in America thanks to his TV program Life is Worth Living, was, predictably, about money, not theology. When Spellman lost that battle, he had Sheen exiled from New York City to upstate Rochester.

The liturgist Aidan Kavanagh, OSB, a former teacher of mine, wrote that “when Cardinal Spellman got dressed up to celebrate pontifical High Mass, it was eerily like watching the Infant of Prague come to life, but an Infant with whom it was advisable not to trifle.” Spellman’s visibility and authority was the embodiment of what made the pre–Vatican II Church so compelling for many. “It was discipline,” Kavanagh wrote. “American Catholicism was a bit corrupt, somewhat crazy, and not a little magnificent.”

Cooney’s book, regarded as too gossipy by some, certainly explains the corrupt and crazy parts. The magnificence is probably best appreciated from a good distance, which was how most lay Catholics knew the cardinal. Cooney reminds us that much of that magnificence was tribal, born out of (mostly) Irish resentment and determination to forge secure footing in a still-Protestant America. Money paved the way. Spellman even made sure certain Catholic-owned department stores did not advertise in liberal newspapers he disagreed with.

My own interest in Spellman stems from the fact that my cousin, Msgr. William B. O’Brien—someone I met only three or four times—was one of “Spelly’s boys.” O’Brien was my father’s age and as a young priest he worked at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in the 1950s, a choice assignment for those Spellman regarded as future “managers.” A staunch Republican, O’Brien was probably one of the seminarians Spellman used to break the gravedigger’s strike. According to one of his close associates, my cousin modeled his priesthood, career, and management style after Spellman’s.

O’Brien was a founder and long-time president of Daytop Village, the drug-rehabilitation program. Like Spellman, he could be an intimidating boss but was loved by the thousands who knew him as the face of Daytop, which practiced a “tough love” approach to rehabilitation. O’Brien insisted on the superiority of Daytop’s approach to recovery, which involved rigorous discipline. Addiction was a “character flaw,” not a psychological problem. He did not tolerate dissent.

Daytop filed for bankruptcy in 2012, and O’Brien died in 2014 at the age of ninety. In 2019 he appeared on the Archdiocese of New York’s list of priests “credibly accused” of sexual abuse. (Spellman was also posthumously accused of groping a West Point cadet.) I don’t know what to make of the abuse accusation against O’Brien. No details will be revealed by the archdiocese. Even former Daytop staffers who were critical of O’Brien were skeptical of the charge. What still strikes me most about O’Brien is his Spellman-inspired cultivation of the famous and powerful, including Richard Nixon, Nancy Reagan, Pope John Paul II, and prominent figures from the world of entertainment and sports. Those endorsements helped him build what was once the largest drug-rehabilitation program in the country and Daytop’s substantial real-estate holdings. Like Spellman, O’Brien seemed to think of himself as a business executive first and a priest second. Because of what he described as the cunning and ruthlessness of drug addicts, O’Brien told the New York Times, he had to “learn a hard discovery. I first had to deal with the human before I could go to the divine. Otherwise, I was building a house on sand.” But what O’Brien built on classic American entrepreneurship and bluster also proved to have a sandy foundation.

In this, too, he was following Spellman’s example. The enormous amount of money Spellman controlled and how he leveraged it to amass extraordinary authority in the American Church, the Vatican, and U.S. politics is still somewhat shocking. He worked in the Vatican from 1925 to 1932, where he learned how to influence prelates and pile up favors with money raised from wealthy American Catholics. He continued to funnel money to a financially desperate Vatican for the rest of his life. During those years in Rome, he became friends with Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli, the future Pope Pius XII, greasing the slippery pole up the hierarchy. Spellman returned to the Boston archdiocese as an auxiliary bishop, much to the displeasure of Cardinal Archbishop William O’Connell, who detested Spellman and was determined to sabotage his advancement. When Pacelli became pope in 1939, he snubbed O’Connell again by naming Spellman archbishop of New York, the wealthiest and most powerful diocese in the country.

In Cooney’s telling, scheming and backstabbing were endemic among clerics and hierarchs, both in Rome and America. Or, as the epigraph to his book notes, “Ambition is the ecclesiastical lust.” When it came to appointing bishops and cardinals, Spellman spoke and Rome obeyed. If Spellman disagreed with the Vatican, as he did about the Vietnam war and U.S. hegemony more broadly, he tended to ignore his superiors.

It is useful to revisit Spellman’s tenure now that so many conservative American Catholics are bemoaning the loss of clarity and unambiguous teaching under this pontificate. To be sure, under Spellman and his acolytes there was plenty of clarity and little ambiguity in what the Church taught and stood for. Just beneath the surface, however, vanity, corruption, and abuse flourished. Recent reports about ongoing scandals with Vatican finances suggest that not much has changed since Spellman was wheeling and dealing on both sides of the Atlantic. “A prince of the Church puts his soul at risk with every cornerstone,” Wilfrid Sheed wrote of Spellman’s need to woo the rich to build his ecclesiastical empire and keep the Vatican out of hock. My cousin had a similar relationship with cornerstones and real estate, which included Daytop’s headquarters building overlooking Bryant Park and the New York Public Library in midtown Manhattan, an asset eventually sold to pay Daytop’s debts. The clear and unambiguous lesson of Church history is that a worldly magnificence is not to be trusted, and that honesty is more important than an air of certainty.