In the second half of the twentieth century, the definition of a public intellectual underwent a gradual but profound change, as generalists gave way to academic specialists. Sinology makes for the perfect case study of this transition. From its origins in the Jesuit missions until the mid-twentieth century, sinology favored breadth over depth; it presumed that an individual scholar could take the whole of Chinese civilization—including its language, art, and history—as his or her subject. This romantic way of approaching the study of China came to an end during the Cold War as sinology, at least in the United States, was fully assimilated into the academic field of China studies. Within this field, there were major disagreements on the proper relationship between scholarship and American foreign policy—but there was, at least, fundamental agreement about what kind of research and books counted as genuine scholarship. As the study of China was professionalized, those who did not specialize were generally looked down upon as dilettantes.

Pierre Ryckmans was one of the last holdouts against this shift. In his biography of Ryckmans, now available in English translation, Philippe Paquet traces an archetypal hero’s journey. Ryckmans’s father was a publisher; his uncles were Belgian colonial governors, professors, and priests, and his family hoped he would follow in one of these paths. But Ryckmans wanted to travel, and he wanted to write. When he was twenty, he went to China as part of a delegation of young Belgians. While there, he got to meet and speak with Zhou Enlai, the first Premier of the People’s Republic of China. He returned from this trip with a passion for China and a sympathy for Maoism. The former would last for the rest of his life; the latter would not. Having finished his studies in art history back in Belgium, he enrolled at National Taiwan Normal University, where he studied under exiled leaders of the Chinese intellectual world. From there he moved to Singapore and then to Hong Kong, researching and teaching art history in relative obscurity.

That changed in 1971 with the publication of The Chairman’s New Clothes, in which Ryckmans exposed the violent factional struggles of the Cultural Revolution. The book shook the French-speaking literary world, where Maoist illusions were still very much in vogue. The political stakes were so high that Ryckmans thought it wise to adopt a pen name, Simon Leys. He would go on to become the cultural attaché for the Belgian embassy in China, publishing numerous books in both English and French, and getting into public scrapes with Roland Barthes and Edward Said, among others. But Leys had other interests, other talents, and over time his work as a literary critic, essayist, and all-around man of letters overshadowed his reputation as a polemicist and academic.

Despite the triumphal arch of Paquet’s narrative, Leys is still not as well known as one might expect. His attacks on Said and Barthes did not leave a mark, and the Maoist intellectuals he vanquished in public controversies (notably Michelle Loi and Maria-Antonietta Macciocchi) are now mostly forgotten. Few now remember the debates that first brought Leys to public attention in France and Belgium. Paquet does his best to depict these as high drama, but one gets the sense that Leys himself regarded them as tedious distractions from his real work. In any case, he was not concerned with parlaying controversy into celebrity. He slyly invoked the words of Jacques Chardonne: “Any truly good book will always find three thousand readers, no more, no less.”

The man that emerges from Paquet’s biography is more complex than the legend; if his journey was in some ways heroic, Leys was not a conventional hero. His greatness was thrust upon him, and he often seemed to dodge it. During the Cultural Revolution, while he was still living in Hong Kong, Ryckmans was invited to a meeting at the Intercontinental Hotel in Kowloon. At the time, he had a young family to provide for on a meager teacher’s salary. For extra income he was writing reports on the Cultural Revolution for the Belgian consulate that would form the basis of The Chairman’s New Clothes. The meeting was set up by a friend from the Yale-in-China organization to encourage Ryckmans to work for the CIA, and the offer included control of his own brief, encompassing intelligence and operations. He was told “money would not be a problem.” Ryckmans declined the offer, explaining that “to successfully conduct such missions, you needed to be rock solid, intelligent and honest: any person who had those qualities could only naturally reject such a proposition.”

The episode is characteristic in a number of ways. It shows Ryckmans’s wit, his wariness of political entanglements, and above all his allergy to crass ambition. He knew that comfort and conventional success often came at the expense of intellectual independence. Because of his disposition, not to speak of his honor, this was not a price he was willing to pay. This story—along with Paquet’s revelation that Leys was “greatly outraged” by the Vietnam War and sympathetic to the Vietnamese Communists—demonstrates that Leys was not the crypto-rightwinger some suspect, and others wish, he was.

Leys’s political writings excluded him from an academic post in Paris. After his brief sojourn as a cultural attaché at the Belgian embassy, he spent the rest of his life as a quiet academic in Canberra, Australia. Quiet but productive. If he was opposed to careerism, he was ambitious enough in his own way. He followed another of Chardonne’s precepts: “Only shoot at big game.” Ambition was evident in his choice of translation projects, from the Analects of Confucius to writings by the father of modern Chinese literature, Lu Xun. Leys also liked to cite a line by Arthur Koestler: “A writer’s ambition should be to trade a hundred contemporary readers for ten readers in ten years, and for one reader in a hundred years.”

Mortality was the flipside of Leys’s fascination with monumentality, and death was a recurring theme of his writing. He concluded his Boyer Lectures of 1996, “Aspects of Culture,” by reflecting on dying as both a returning home and a going abroad. The final essay in The Hall of Uselessness, a collection published a few years before his death, is titled “Memento Mori.” His one novel, a tragicomedy in which Napoleon returns from exile only to perish in anonymity, is titled The Death of Napoleon.

But no one who has read Leys’s work would describe it as morbid. It is attentive to beauty (Chinese calligraphy was a lifelong interest), to moments of grace, and, most importantly, to the power of the imagination. That power could be dangerous of course, as in the case of the self-deluding Western Maoists against whom Leys positioned himself as a sober truth-teller. But in one of his best essays, Leys praises Don Quixote precisely for his “refusal to adjust the hugeness of his desire to the smallness of reality.” Leys himself struck a delicate balance between hope and resignation. He tried to live without illusions, but he also knew that reality is often larger and more mysterious than it looks to the naked eye.

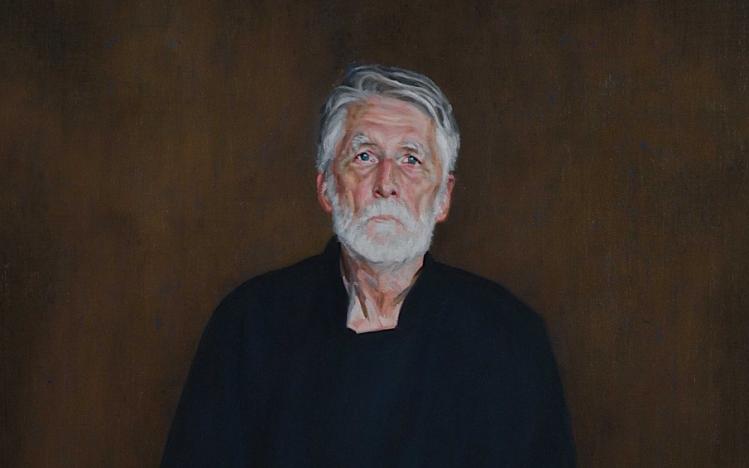

Simon Leys

Navigator between Worlds

Philippe Paquet

Translated by Julie Rose

La Trobe University Press, $59.99, 692 pp.