In the brief introduction to Distant Journeys, a new collection of photography assembled from trips undertaken over nearly five decades and across six continents, David Katzenstein tells us that his “passion for discovery” began early. Perhaps it was when he was only three years old, gripping his father’s back as their “frisky gray mare” galloped across a beach in Cuba, or when he visited Norway at age seven and watched a waterfall plunge half a kilometer into the sea below. It’s not surprising that he became a photographer: both memories, distant but visually and metaphorically precise, evoke the shifting perspectives that have defined his work throughout his career.

At first glance, the few images presented here, though taken in places as far-flung as Senegal, India, and Sicily, are neither exotic nor extraordinary. They show people going about their daily lives: milling around in a market, dancing in a sweaty living room, snapping photos at a festival with their phones. But there’s mystery here, too. In the mosaic-like array of human faces that comprises many of Katzenstein’s compositions, we can practically feel the curiosity of his lens, its desire not so much to penetrate and possess the inner lives of his subjects, but rather to simply abide in their presence, to bear respectful witness to their irreducible complexity and inalienable dignity. If each photo captures a single moment in time, it also conveys an entire arc of attentiveness: the photos only appear casual, masking the considerable preparation and effort Katzenstein completes beforehand. Shooting from a position of wonder, he can simply allow scenes to unfold.

One of the truisms of travel is that seeing new things can help us “expand our horizons” and escape the limits of the self. Katzenstein’s photography, the product of a gaze at ease and a mind at peace with itself, seems to suggest that this gets it exactly wrong. It’s in going out and discovering what we’re drawn to that our souls come home, and we begin to know ourselves.

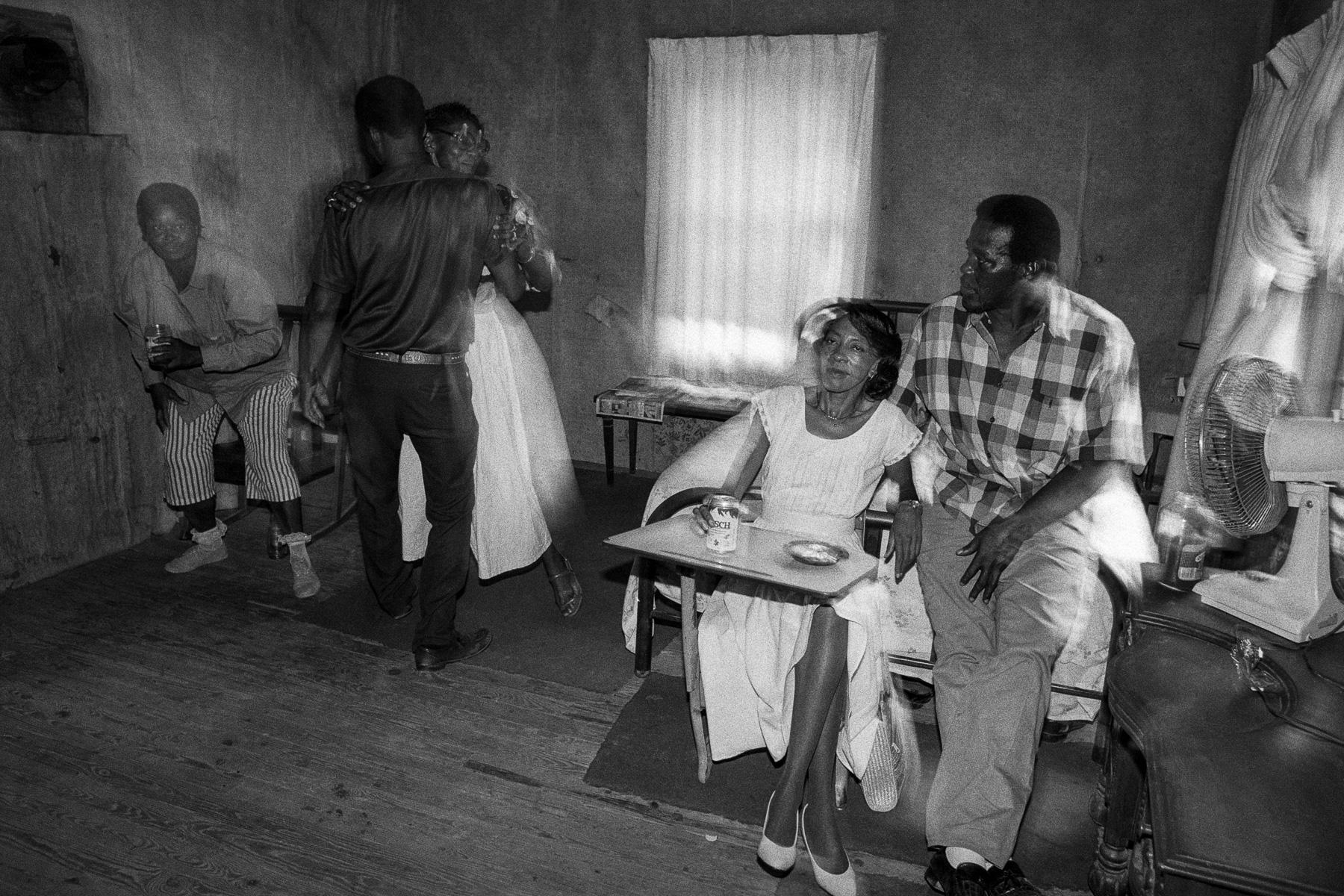

Above: House Party, Holly Springs, Mississippi, 1988

You can practically smell the sweat and hear the floorboards creak as one couple dances while another rests. The two women on either end of the composition—one about to crack a smile, the other more tactfully reserved—appear to be looking at and through Katzenstein’s lens.

Below: Untitled #10, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India, 1995

Though the market scene is bewildering, Katzenstein finds a pocket of stillness as he anchors himself in a corner just outside the flow of traffic. It’s a record of seeing, but also of being seen, not only by riders of Vespas and bicycles, who avoid running into him, but also by a curious woman who gazes at him directly from the back of her carriage.

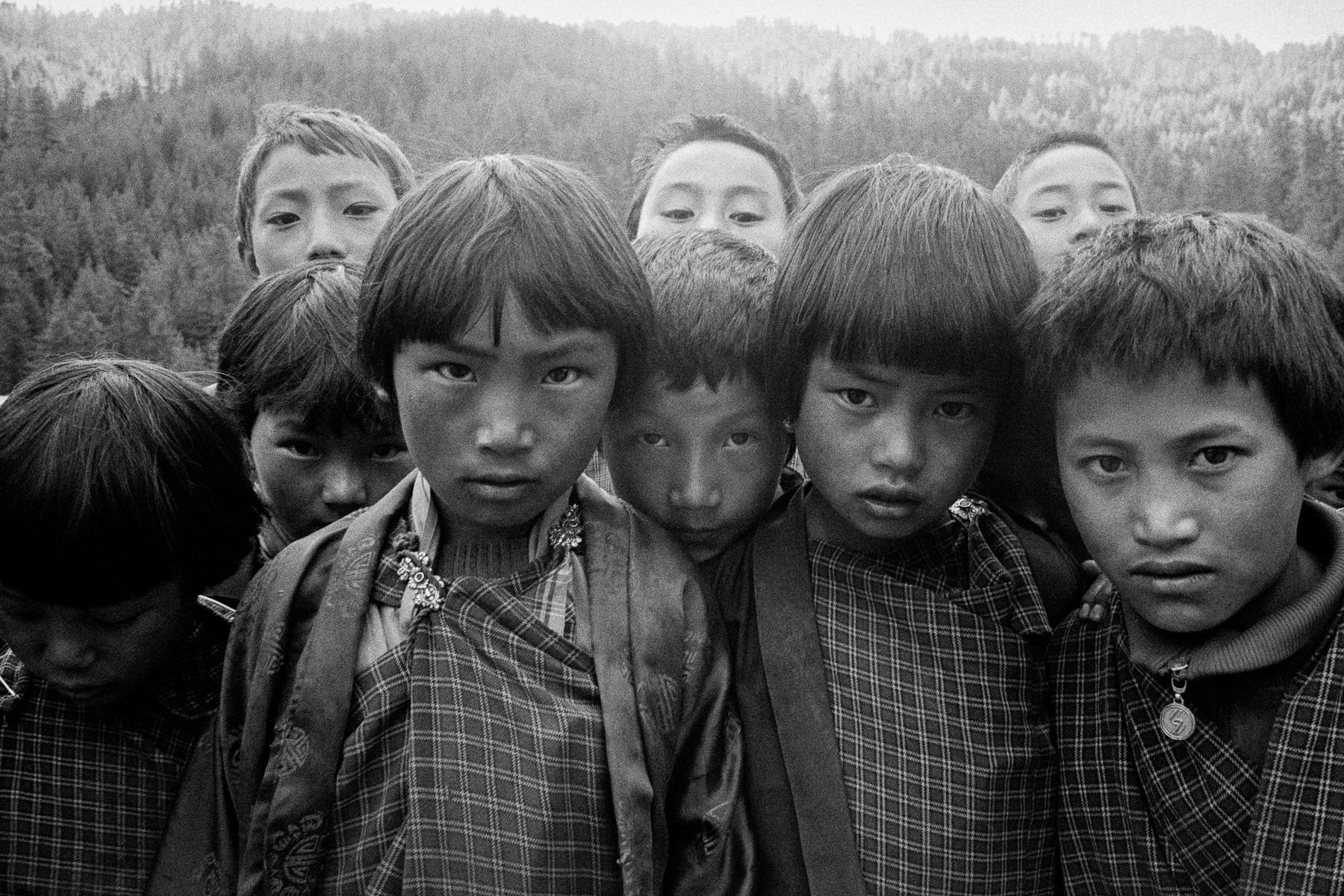

Above: Schoolchildren, Tang Valley, Bhutan, 1999

The shaggy heads in the foreground resemble the rolling hills in the background. The first row of children’s faces appear diffident and skeptical; the eyes of their peers in the two rows behind are more playful, even impishly inquisitive.

Below: Festa di Santa Lucia delle Quaglie, Ortigia, Syracuse, Sicily, 2023

Each May, the people of Syracuse commemorate the miraculous arrival of a fleet of ships laden with food, heralded by doves flying into the Duomo. The provisions saved the city’s starving citizens from famine in 1646. Here, we see the festivities reflected in the lenses—both sunglasses and cell phones—of their descendents as they witness the procession of the statue, or simulacro, of Santa Lucia. It’s a testament to the power that images still hold.

Below: Caribbean Seascape, 2023

Another landscape and another horizon, the sea’s relative calm heightened by the dramatic line of clouds blocking and filtering the sun’s rays. What is true of photography is also true of prayer, as the grandeur of what can be seen is dwarfed and exceeded by whatever lies beyond.