In an essay on the voluble New York intellectual Dwight Macdonald, George Scialabba cites Lionel Trilling’s assessment of Orwell, who, for Trilling, exemplified “the virtue of not being a genius, of fronting the world with nothing more than one’s simple, direct, undeceived intelligence, and a respect for the powers one does have, and the work one undertakes to do.”

Much the same could be said of George Scialabba. For forty-four years, he has made a gift of his “direct, undeceived intelligence”—I would not say “simple”—to those fortunate readers who, as Richard Rorty once recommended, “stay on the lookout for [his] byline.”

Scialabba’s new collection, Only a Voice, contains twenty-eight previously published essays, the earliest from 1984, the latest (from this magazine) in 2021. They’re gathered here with a new introduction that takes up a perennial question for Scialabba—“What are intellectuals good for?”—and an apposite epigraph from Auden’s “September 1, 1939.”

Rorty isn’t alone: Christopher Hitchens, Norman Rush, James Wood, and Vivian Gornick have all, at various times, proclaimed their membership in the informal Association of Scialabbians. Scialabba, it has been said, is a “critic’s critic,” which, like being called a “songwriter’s songwriter” or a “comic’s comic,” is a way for more successful peers to laud his singular talent—as another admirer described it, “skeptical without being cynical, earnest without being sanctimonious, and truthful without being a scold”—while thanking him for remaining courteously unfamous.

We love geniuses, Trilling says, but they are discouraging. “We feel that if we cannot be as they, we can be nothing. Beside them we are so plain, so hopelessly threadbare.” In the decade-and-a-half that I have been reading Scialabba, I have often envied a piquant turn of phrase, marveled at the economy of a synthesis, wished to be so well-read, to possess his daunting breadth of reference, his ease and unsentimental sincerity; and I have, at times, quailed at the plainness (or else, the needless flamboyance) of my own prose by comparison. But never, not once, has reading Scialabba made me feel discouraged.

What I have felt most consistently is gratitude. Scialabba toiled for thirty-five years at a desk job in the windowless basement of Harvard’s Center for Government and International Studies, writing book reviews in his spare time; he has much to say about the economic conditions that enable or disable the life of the mind. (A sufferer from chronic depression, Scialabba credits his union for enabling him to take several paid medical leaves. “This is one of many ways in which strong unions are a matter of life and death,” he writes in How To Be Depressed.) And yet, for Scialabba, the essence of intellectual and creative exchange remains a gift economy: “When we’re young, our souls are stirred, our spirits kindled, by a book or some other experience,” he once said, “and in time, when we’ve matured, we look to pay the debt, to pass the gift along.” Gratitude, deeply felt, enables generosity. And never has a writer of such enviable talents displayed such undiminishing patience for his reader, such evident and unpretentious pleasure in the pedagogical function of good prose.

In this way, Scialabba models another virtue: the virtue of not being scornful—or only sparingly so. (He permits himself a special dispensation when it comes to mendacious architects of war like Henry Kissinger, Dick Cheney, and Donald Rumsfeld.) In almost every other instance, Scialabba adheres to Matthew Arnold’s standard of disinterestedness, which Scialabba summarizes thus: “To perceive as readily and pursue as energetically the difficulties of one’s own position as those of one’s opponents; to take pains to discover, and present fully, the genuine problems that one’s opponent is, however futilely, addressing.”

It would not be wrong, exactly, to call this sensibility “liberal.” (Arnold certainly would.) Scialabba shares with figures like Trilling, Rorty, and Irving Howe the constitutive liberal trepidation: the fear that he might be mistaken. (In my experience, conservatives are much less afflicted by this anxiety.) Scialabba distinguishes himself, however, from the run of self-doubting liberals by refusing to allow such fear to paralyze his judgment or extinguish his passion. Political commitment, after all, cannot be ignited or sustained by skepticism alone. Of Howe’s Dissent magazine, Scialabba writes, “[it] aims to produce a refined and complicated political awareness among its readers. It’s a noble aim. But someone or something else must first have produced an elemental political awareness.” Quite so. As Scialabba insists in the introduction to Only a Voice, a man or woman of the Left must cultivate “discrimination” and “democratic passion” both. Without a comparable measure of each, one will starve the other.

One can imagine Scialabba, had he not abandoned his youthful theism, reciting in earnest John Stuart Mill’s prayer for his opponents: “Lord, enlighten our enemies…. Sharpen their wits, give acuteness to their perceptions, and consecutiveness and clearness to their reasoning powers. We are in danger from their folly, not from their wisdom: their weakness is what fills us with apprehension, not their strength.” When Scialabba encounters folly in the arguments of his interlocutors—whether they be agonized Cold War liberals like Isaiah Berlin, despairing conservatives like Leo Strauss and Eric Voegelin, or fellow travelers of the fretful, beleaguered Left, like Christopher Lasch, Howe, and Trilling—he does so with an air of disappointment rather than disdain. Put simply, he is fair. And to be treated fairly by George Scialabba, as, for example, Christopher Hitchens was in the pages of n+1 in 2005, can be a far more devastating fate than being treated shabbily by a thousand less scrupulous critics.

The only moments in Only a Voice where Scialabba failed to live up to his own fairness doctrine were in brief asides about “cancel culture” and “identity politics.” It isn’t that I disagree with all of his assertions (e.g., that Yeats was a great poet despite sympathizing with fascists; Lawrence a great novelist despite flirting with authoritarianism; that Flannery O’Connor’s use of the n-word and her “instinctive” sympathy for segregation shouldn’t distract from the richness of her Black characters nor her support for integration “in principle”; that Saul Bellow and Philip Roth could be pigs, but they were “master stylists and storytellers”). The problem is that these thrusts are directed at an absent and perhaps imaginary interlocutor: a caricature.

It doesn’t surprise me in the least that Scialabba—a man whose chief intellectual virtue is generosity, and whose chief personality trait is reflexive, practically clinical, self-effacement—would quarrel with the more sanctimonious and censorious tendencies of the contemporary Left. Indeed, I suspect he disdains the vogue for “cancellation” not out of fear or defensiveness, but because it strikes him as, frankly, shabby behavior enabled by imprecise thinking and often leading to disproportionate outcomes. We all might have profited from an essay by Scialabba on the subject. However, to meet his usual standards, such an essay would need to be engaged with by an actual proponent of “cancel culture,” or at least a steel-manned version of the argument in favor of, say, using socially networked crowds to mete out punishment against perceived moral deviants, or judging great writers’ creative output by their private behavior. Here Scialabba has failed to take pains to discover and present fully “the genuine problems” that his opponents are, “however futilely, addressing.” This brief round of shadowboxing in Only a Voice is beneath him.

While the essays in Only a Voice are not new, the collection is enlarged by a subtle maneuver of its structure: Scialabba divides his subjects into partisans and opponents of modernity. “In this volume,” Scialabba writes in the introduction, “I’ve lined up D. H. Lawrence, T. S. Eliot, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Christopher Lasch, Ivan Illich, and Wendell Berry for the prosecution; Vivian Gornick, Ellen Willis, and Richard Rorty (and in some cases, me) for the defense.”

Assessing the mixed blessings of modernity is an abiding aspiration of Scialabba’s work. The “supreme drama” of his life, he writes, was his own “mini-heroic auto-emancipation” from the rigid Catholicism of his youth (toward the end of which he joined Opus Dei) into what Peter Gay calls “the Party of Humanity,” or the Enlightenment project. With supreme Scialabbian coyness, he refers to his own preference for progress, science, and freedom over tradition, revelation, and hierarchy as a “prejudice”—that is, not solely attributable to reason, and partially the consequence of personal affections, disaffections, and happenstance. Likewise, his anxiety about modernity’s bitter fruits is personal, too: Scialabba’s loss of faith was accompanied by his first debilitating depression, one which kept him from intellectual labor for a decade.

Discovering how to live well in the light of reason, how to resist both the disenchanted despair of conservatism and the hollow decadence of liberalism, how to cultivate the virtues of trust, solidarity, and self-discipline without God, within mass democracy, and while defending liberty—this, it seems to me, has been the central project of Scialabba’s long career.

What the essays in Only a Voice demonstrate beyond doubt is that anxiety and ennui about the modern—about its tendency to flatten, diminish, and anesthetize; to trivialize what is Good and Great in civilization—is as essential a feature of modernity as utopianism, rationality, or skepticism. Modernity was barely underway before its most eloquent critics (most of all, Nietzsche) arrived to spell its ruin. Spake Zarathustra: “‘We have invented happiness,’ say the last men, and they blink.” Spake Tocqueville: “In modern society…all things threaten to become so much alike that the peculiar characteristics of each individual will be entirely lost in the uniformity of the general aspect.” Spake Ortega: “The characteristic of the hour is that the commonplace mind, knowing itself to be commonplace, has the assurance to proclaim the rights of the commonplace and to impose them wherever it will.” Even partisans of progress like Mill, Scialabba notes, lament that “the general tendency of things throughout the world is to render mediocrity the ascendant power among mankind…. [A]t present individuals are lost in the crowd.”

Scialabba sides (officially) with Rorty’s minimalist defense of modernity, which concedes “to Nietzsche that democratic societies have no higher aim than what he called ‘the last men’—the people who have ‘their little pleasures for the day and their little pleasures for the night.’” In other words, that we moderns will never be assured by anything larger than ourselves, anything other than our own rationality, and that those citizens of modern societies who have a “taste” for the sublime “will have to pursue it on their own time.” After all, affording the mass of humankind the time, resources, and opportunity to pursue their pleasures—little and large—for the first time in history is nothing to sniff at. But is it enough? And at what cost? Scialabba can’t resist working “the other side of the street for a while.”

If I were to attempt to synthesize where he winds up, it would be something like this: the Enlightenment trinity of reason, progress, and freedom is a precious inheritance, which should be defended against the predations of the authoritarian Right and the trepidations of the liberal center. But modernity has a dark side; highly technological, bureaucratic, and consumerist societies fail to cultivate the virtues necessary for human flourishing. What’s more, efforts to reassert the egalitarian dimensions of liberal progress—through, say, mass mobilization and class conflict—are also doomed by the waning of these virtues, which means the forms of political engagement imaginable by contemporary leftists are constrained by an increasingly enervated, mistrustful, and self-centered modern character.

For solutions, Scialabba tends to look to anti-modernist radicals like Lasch, Berry, and Illich, who lament the turn of our culture away from “the immediate, the instinctual, the face-to-face.” Here, I’ll quote Scialabba at his most prescriptive:

It is the practice of demanding skills, rather than fragmented and routinized drudgery, that disciplines us and makes mutual respect and sympathy possible. Work that provides scope for the exercise of virtues and talents; a physical, social, and political environment commensurate in scale with our authentic, non-manufactured needs and appetites; and a much greater degree of equality, with fewer status distinctions, and those resting on inner qualities rather than money—these are the requirements of psychic health at present. The alternative is infantilism and authoritarianism, compensated—at least until the earth’s ecology breaks down—by frantic consumption.

It strikes me, however, that Scialabba misses an essential defense of the modern, which arises from the pattern of his own thought. If anti-modern anxieties are an irreducible feature of modernity, then perhaps we should say that “the modern” man or woman is not necessarily a conformist, a face in the crowd, incapable of independent thought, or disinterested in the higher pursuits of being…rather, he or she is someone who detects these frailties in everyone else. These moderns are defined by their doubts about the individuality of others, whom they dismiss as so many blinking cattle satisfied with meaningless little pleasures. Perhaps one of the virtues that modernity corrodes—at least among intellectuals—is confidence in, and curiosity about, the other, the stranger, the neighbor. Conveniently for its enemies, mass democracy depends on precisely this imaginative sympathy.

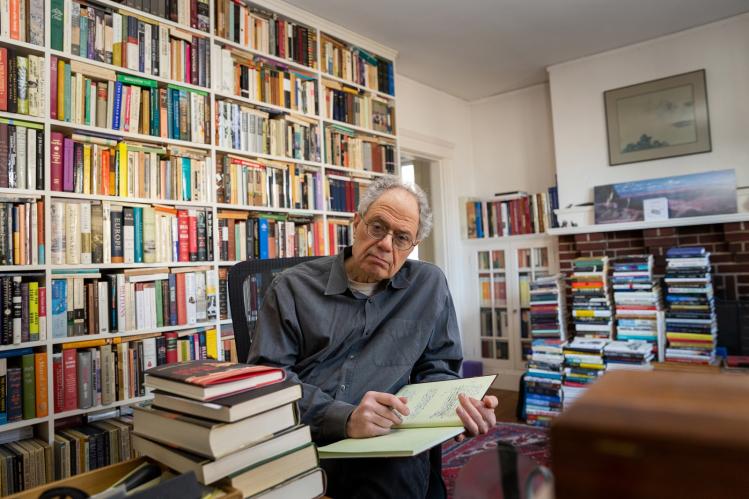

Commentary on Scialabba often makes much of his marginal status in relation to the more glamorous—or, at least, more lucrative—centers of intellectual life. As Christopher Lydon once put it, he has “no tenure…no tank to think in, no social circle, no genius grant (yet), no seat in the opinion industry or on cable TV—‘no province, no clique, no church,’ as Whitman said of Emerson—not even a blog.” In this, there was always a note of condescension: the working-class boy from Sicilian East Boston made good (but not good enough for the academy).

Today it feels not just anachronistic but superfluous to repeat this litany of faint praise. Who would still assume that “the best that has been said and thought” (to quote Arnold again) is being said or thought by academics, think tankers, TV personalities, or MacArthur grant awardees? Who, indeed, would be surprised to find that the most stylish, mature, adroit, and winsome thinkers are those entirely untainted by contact with the ideas industry?

When I started writing this review, I resolved to avoid the mawkish, almost elegiac tone that often seeps into essays about Scialabba. As you can see, I’ve failed. It can’t be helped. Like any great teacher, he inspires great loyalty in his pupils. As for the elegiac, if an aspect of mournfulness attaches to these sentences, it is because one feels, and fears, the disappearance of Scialabba’s type—the “exemplary amateur”—from the intellectual scene.

The amateur is a distinctly American type, a figure of both humility and hubris; he leads a learned revolt against titles, credentials, and expertise. As Scialabba writes of antiwar radicals like Randolph Bourne, Henry David Thoreau, Macdonald, and Noam Chomsky, “they asserted a kind of protestant principle of private judgment against the quasi-theological mystifications of the government and the policy intelligentsia.”

Only outside—or in Scialabba’s case, below—the halls of intellectual officialdom, where the edicts of American exceptionalism lack pontifical authority, does this heretical tradition flourish. The exemplary amateur has no patron, no stature, no sanction (besides his own integrity), and only a voice—a curious, bookish, humane, ironic voice—“to undo the folded lie.” The amateur cajoles, informs, punctures. He cannot declare from on high, because he isn’t up there. He’s down here with us, modeling Scialabba’s favored virtues: “Probity, fearlessness, tact.” Reading Scialabba, one feels hopeful that those could be our virtues too. As Trilling said of Orwell, “He is not a genius—what a relief! What an encouragement.”