Acedia is Walker Percy’s great theme, and there is no place for it in America precisely because we have always been puzzled or embarrassed by lives of contemplation.

—Mary Gordon

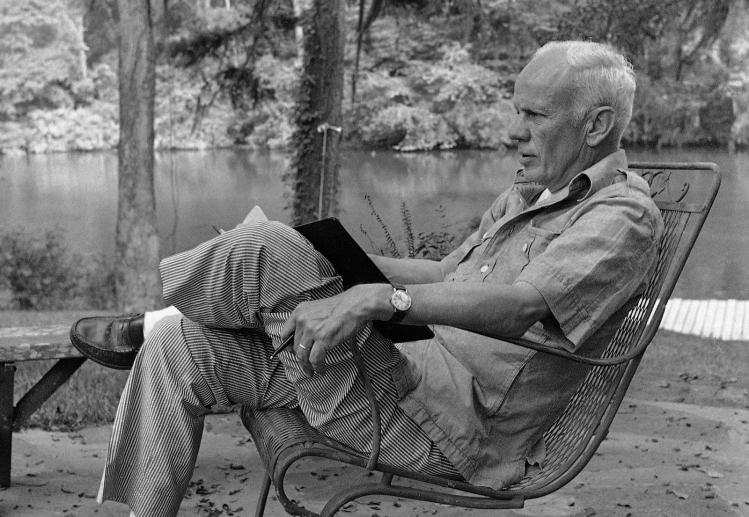

In 1972, Lancelot wasn’t coming off as cleanly as Walker Percy would have liked. He was under intense, self-imposed pressure to produce another critically successful novel. A relatively new empty-nester, he was also drinking more heavily than usual, and was in something of a crisis of faith. Writing to his friend Shelby Foote, he said, “I’ve been in a long spell of acedia, anomie and aridity in which, unlike the saints who write under the assaults of devils, I simply get sleepy and doze off.” Percy being Percy, he inserts a wry, self-deprecating note into his reportage, but his travail with the affliction was very real.

Two years later, he was still struggling. His novel was a little closer to being finished, but then he contracted hepatitis. He became depressed. Writing to Caroline Gordon in June of 1974, he told her,

My hepatitis and depression are better. Maybe one caused the other. Truthfully I don’t know whether I’ve been overtaken by a virus or male menopause or the devil—who I am quite willing to believe does indeed roam about the world seeking whom he may devour. Anyhow it takes the form in my case of disinterest, accidie, little or no use for the things of God and the old virtues. I’d rather chase women (not that I do, but how strange to have come to this pass). I think it has something to do with laziness or the inability to give birth to a 2-year-old fetus of a novel. I don’t like it at all and keep tearing it up. I feel like a Borgia Pope, I still believe the whole thing, but oh you Italian girls!

Acedia made its way into modern parlance as sloth, a word we now associate with the supposedly benign vices of laziness or idleness. Percy knew better. In these couple of instances, he does indeed mention laziness and sleepiness, but he does so in the context of acedia’s more classic associations: as a complex, subtle, destructive habit of the soul—with a possibly demonic origin—that neglects the weightier matters of love of God and neighbor for more immediately gratifying pleasures. Moreover, he interprets acedia not just as an arcane spiritual malady of early monastics. Rather, it is a widespread, distinctly modern phenomenon that “has settled like a fallout,” as he says in The Moviegoer, and it is capable of imposing itself upon the modern person regardless of his or her affiliation with the religious life.

A wily demon, acedia is difficult to pin down. It’s a trickster, a shapeshifter, a boggart. It goes out of focus when you try to look directly at it. The term itself defies translation: despondency, sloth, lassitude, ennui, melancholy—each displays an aspect, none the full image.

The desert monks who first wrestled the demon acedia to the ground did so by grinding through their prayers in the pitiless heat of the Egyptian wilderness. In doing so they became superbly intimate with their failures. Evagrius had a theoretical bent and began cataloging the modes and patterns of failure he and his fellow monks encountered. Eventually he placed acedia at the center of a spectrum comprising the “eight thoughts,” the fountainhead of the seven-deadly-sins tradition. On the one side of the spectrum, he said, lie our animal or material vices; on the other, the vices of the intellect. Acedia, he said, is “the complex thought” because it stands at the center of the spectrum and thus assimilates aspects of both the material and the intellectual into itself.

Acedia causes the soul, hovering between a person’s animal nature and rational intellect, to shrink from contemplation or the possibility of contemplation. Reluctant to ascend to pure intellection, it becomes possessed of lethargy and stupefaction. Aridity and ennui take hold, giving rise to restlessness, mania, indolence, somnolence, discouragement—whatever will do to turn the face away from the fire of God’s love. The habit of acedia terminates in the failure of all hope. Acedia in extremis eventuates in despair and in some cases suicide. Thomas Aquinas says acedia pulls apart the constituent parts of the human being and then causes us to mistake the physical, transitory part of human existence for the whole. He calls this mistake “animal beatitude.”

The fundamental paradox of acedia lies in the fact that contemplation must be a possibility in order to experience it. Acedia is so dangerous because it involves a denial of the possibility that God has in fact saved us in the Incarnation. And it is so subtle because it manifests not as rebellion but by sedimenting into the habit of despair. Aquinas’s animal beatitude is not defiance of God but a loss of concern for salvation, a kind of spiritual disintegration. One might even notice one no longer cares about one’s salvation, but one doesn’t care that one doesn’t care.

Earlier in his career, Percy had written about a related phenomenon, what he called “the malaise”—a sense of spiritual illness and alienation. It emerges in The Moviegoer as one part of a larger moral taxonomy of the modern world: awareness of everydayness gives rise to the malaise, and the malaise in turn gives rise to “the search.”

“The search,” says Jack “Binx” Bolling, in some of the most famous lines Percy ever wrote, “is what anyone would undertake if he were not sunk in the everydayness of his own life.” Binx goes on, “To become aware of the possibility of the search is to be onto something. Not to be onto something is to be in despair.” The malaise, by contrast, occurs when one becomes aware of everydayness and finds it unbearable. Hence the book’s epigraph, from Kierkegaard’s The Sickness Unto Death: “The specific character of despair is this: it is unaware of being despair.” And despair, says Thomas Aquinas, “is the first and most terrible daughter of acedia.”

So the malaise, which is no picnic, at least indicates that something is off, like a moral “check engine” light, alerting us to the distance between our desires and the world indifferent to them. Binx, by giving everydayness a name, has unmasked the demon of acedia. “Losing hope is not so bad,” he says. “There’s something worse: losing hope and hiding it from yourself.” The search in turn becomes a mode of contemplation.

Binx tells the reader early on in The Moviegoer that he used to read only “fundamental” books, such as War and Peace and Schrödinger’s What Is Life?—books that he thought would give him mastery over the world. Percy identifies two types of modern people: the theorist and the consumer. Theorists master the world according to abstract generalizations, eliminating the individual person. Consumers, Percy says, participate in “the goods and services of scientific theory”; but as passive, second-tier actors with regard to the ascendant philosopher-kings of modern science, they remain latently dissatisfied. Binx might be said to have renounced the life of the theorist only to have taken up the life of the consumer. Having been involved in scientific research on kidney stones in pigs, he instead became enchanted by the wonder of the world around him, gazing at dust motes in shafts of late-afternoon sunlight. Binx’s renunciation of the life of a theorist resulted from his encounter with something that was calling him beyond everydayness. But he failed to heed the summons of the search and instead slouched into the life of the consumer, pursuing money and women and hiding his despair from himself. Only years later does he notice the failure. The novel turns on his waking himself up from acedia, from the death-in-life of everydayness, and embarking on the search.

The product of both theory and consumption, Percy says, is “sadness and anxiety.” Aquinas says in reference to acedia that “no one can remain in sadness”; we can’t bear it, so we resolve it in some other action. One route we take away from sadness and anxiety is harm—of ourselves and others. Percy says that the denizen of the modern world, whether theorist or consumer, “can become so frustrated, bored, and enraged that he resorts to violence, violence upon himself (drugs, suicide) or upon others (murder, war).” But acedia, or everydayness, presents an opportunity not only for violence but also for real contemplation. Those cast out from both theory and consumerism have the opportunity to open themselves to the risk of something more. “In the old Christendom,” Percy says, “everyone was a Christian and hardly anyone thought twice about it. But in the present age the survivor of theory and consumption becomes a wayfarer in the desert, like St. Anthony; which is to say, open to signs.”

Acedia, once overcome, gives way to prayer. “Prayer,” Evagrius says, “is the elimination of sorrow and dejection.” In a way, then, acedia is the threshold of contemplation, provided one is willing to sit with it rather than flee from it. Spending the night at his mother’s cabin, Binx says he is “locked in a death grip with everydayness, sworn not to move a muscle until I advance another inch in my search.” When he does advance, it is by overcoming his “invincible apathy”—another daughter of acedia.

Though The Moviegoer focuses on Binx’s interior life, there are scattered notices throughout that the everydayness of acedia is the generalized condition of the modern world. Binx clearly believes that his own battle with everydayness and malaise is emblematic of a larger spiritual death at work. “For some time now,” Binx says, “the impression has been growing on me that everyone is dead.” While a cousin talks to him earnestly of her “enduring values” and how she loves reading Kahlil Gibran in front of the fire, Binx wonders to himself, “Why does she talk as if she were dead?” Their brief exchange having ended, she and Binx part ways, “laughing and dead.”

Percy’s gaze turned outward in his subsequent work. In 1971, he said that Love in the Ruins “deals, not with the takeover of a society by tyrants or computers or whatever, but rather with the increasing malaise and finally the falling apart of a society which remains, on the surface at least, democratic and pluralistic.” By 1986, in fact, when asked by an interviewer, “Is there any concrete issue that engages your attention most in connection with what is going on in America at the moment?” he could answer, “Probably the fear of seeing America, with all its great strength and beauty and freedom...gradually subside into decay through default and be defeated, not by the Communist movement, demonstrably a bankrupt system, but from within by weariness, boredom, cynicism, greed, and in the end helplessness before its great problems.” The interviewer follows up: “In connection with what is going on in the world?” Percy’s response: “Ditto: the West losing by spiritual acedia.”

If Binx Bolling is set apart by his awareness—and ultimate overcoming—of everydayness, Tom More in Love in the Ruins is emblematic of a generalized modern malaise, as much a victim of the dystopian American landscape as an observer of it. More, a psychiatrist in Paradise, Louisiana, suffers from acedia and has settled for animal beatitude. Here is how he introduces himself:

I, for example, am a Roman Catholic, albeit a bad one. I believe in the Holy Catholic Apostolic and Roman Church, in God the Father, in the election of the Jews, in Jesus Christ His Son our Lord, who founded the Church on Peter his first vicar, which will last until the end of the world. Some years ago, however, I stopped eating Christ in Communion, stopped going to mass, and have since fallen into a disorderly life. I believe in God and the whole business but I love women best, music and science next, whiskey next, God fourth, and my fellowman hardly at all. Generally I do as I please. A man, wrote John, who says he believes in God and does not keep his commandments is a liar. If John is right, then I am a liar. Nevertheless, I still believe.

This passage—which strongly echoes Percy’s description of his own experience of acedia—presents the central issue of Tom More’s moral development in the book. Most interpreters of Percy’s novels identify pride as More’s besetting vice, which is true as far as it goes, but the Christian moral tradition places pride at the root of all sins, and the seven deadly sins in particular. More’s flippant little hierarchy of loves, however, bears all the hallmarks of acedia, particularly the indifference toward the things that make for one’s salvation. More tells his colleague Max Gottlieb, for instance, that he is troublingly untroubled by his own fornication. Max, a behaviorist, assumes that Tom is troubled by feelings of guilt. But More insists it is precisely the “not feeling guilty” that troubles him.

At the end of the novel, when More has mostly overcome his acedia, he has a similar, in fact almost exactly parallel, conversation with a priest named Fr. Smith. Although the spiritual progress he has made has gotten him as far as the confessional, More still can’t drum up enough contrition to make an adequate confession. He apologizes for not feeling sorry for his sins. While Max was concerned for Tom but didn’t understand his predicament, Fr. Smith understands it but isn’t much concerned, offering stock moral advice that Tom doesn’t find helpful. When they’ve just about had enough of each other—Tom frustrated with Fr. Smith’s formulaic answers and Fr. Smith exasperated and bored with this troublesome, self-centered parishioner—the priest finally snaps at Tom:

Meanwhile, forgive me but there are other things we must think about: like doing our jobs, you being a better doctor, I being a better priest, showing a bit of ordinary kindness to people, particularly our own families—unkindness to those close to us is such a pitiful thing—doing what we can for our poor unhappy country—things which, please forgive me, sometimes seem more important than dwelling on a few middle-aged daydreams.

This little tirade, which could have come out of the mouth of a desert father, scalds Tom and shames him, and he and Fr. Smith are both surprised and delighted to find that it has produced a true sense of contrition in Tom—not simply for his lust but for the root failure to love his neighbor. Hard work and service to others, moreover, are classic remedies for acedia.

Equipped with his “ontological lapsometer,” More believes he can overcome the Cartesian split between body and soul. But a scientific instrument designed to address spiritual-metaphysical problems is something of a category error. Imagining in his hubris that he can address humanity’s spiritual problems by means of a technology, More is—literally, as it will turn out—of the devil’s party without knowing it.

More’s repeated references to angelism and bestialism, or to the compound problem of angelism-bestialism, correspond to the literal disintegration of the human person wrought by Cartesian modernism. The two aspects of human nature, animal and spiritual, have been split like Jekyll and Hyde, then ungracefully stitched back together. Because the two parts are not actually integrated, man is alienated from himself. “How can a man spend forty-five years as a stranger to himself?” More asks. “No animal would, for he is pure organism. No angel would, for he is pure spirit.” This is what More calls “Lucifer syndrome,” which results from the abstracted, angelic self’s “envy of the incarnate condition and a resulting caricature of the bodily appetites.”

More hopes his lapsometer will be able to reintegrate these two parts of human nature: “What if man could reenter paradise, so to speak, and live there both as man and spirit, whole and intact man-spirit, as solid flesh as a speckled trout, a dappled thing, yet aware of itself as itself!” Such a man would not thrash destructively between his angelic and animal nature but would be perfectly integrated, perfectly himself. He would be a “sovereign wanderer, lordly exile, worker and waiter and watcher.”

It’s possible Tom More understands the problem with his plan better than he is willing to admit, even to himself. Prior to the events of the novel proper, More slashed his wrists on Christmas Eve and was saved by Max Gottlieb. His suicide attempt followed a tragic series of events—events that give the novel a deep undercurrent of pathos beneath the frothy surface of dystopian farce. First, More’s daughter, Samantha, died slowly from a brain tumor. Then his wife left him for a New Age spiritual guru. In the psych ward recovering from his wounds, More comes on to his nurse, but later repents:

Lust gave way to sorrow and I prayed.... Dear God, I can see it now, why can’t I see it other times, that it is you I love in the beauty of the world and in all the lovely girls and dear good friends, and it is pilgrims we are, wayfarers on a journey, and not pigs, nor angels. Why can I not be merry and loving like my ancestor, a gentle pure-hearted knight for our Lady and our blessed Lord and Savior? Pray for me Sir Thomas More.

While More himself dismisses this insight with an ironic “etcetera etcetera,” it is exactly what Percy wants the reader to see: all our loves are coded signs for the presence of God in creation. Or, as Percy puts it in an essay, More catches a “glimpse of the goodness and gratuitousness of created being”—even if he is incapable of fully recognizing it as such.

What does all this have to do with acedia? As the ultimate antidote to acedia, Thomas Aquinas recommends nothing less than the Incarnation itself. Acedia is a malady that pulls apart the animal and rational parts of our nature and pits them against each other. As the archetype of humanity, the incarnate Christ, fully God and fully man, not only perfectly joins body and mind and thus heals our deformed, schizoid human nature but also bears in himself the fullness of God’s sacramental presence in creation.

More’s daughter is repeatedly associated with his lost happiness and ability to love. In remembering going to Mass with Samantha, More speaks of the Eucharist in the very terms he uses to describe the intended effects of his lapsometer, the reconciling and reintegration of the angelic and bestial tendencies of sinful humanity: “It took religion to save me from the spirit world, from orbiting the earth like Lucifer and the angels,” he says. “It took nothing less than...eating Christ himself to make me mortal again and let me inhabit my own flesh.” The healing of acedia is mediated primarily through Christ’s perfect humanity in the Eucharist.

More is finally able to overcome acedia by confronting the latent pain of loss that he has been unwilling to address. Thrashing around for scientific solutions to metaphysical problems, devoting most of his idle thoughts to sexual liaisons, drinking Early Times, having it out with the diabolical Faustian interloper Art Immelmann (has More conjured the demon of acedia?)—all of this is the avoidance of despair caused by acedia, a failure to rise to the demands of love of God and neighbor.

Nicole Roccas, who has written perceptively on acedia, connects the vice with pain. Those who experience deep pain avoid probing the memories, just as one hesitates to touch a tender wound. Remember Aquinas: no one can remain in sadness. Just before he “exorcises” Art Immelmann, More is interrupted by his memory of Samantha, and he admits that it broke his heart when Samantha died. What’s more, he recognizes that he has used her suffering and death as a pathetic justification for his destructive desires, and he apologizes to her. Then he asks: “Is it possible to live without feasting on death?”

Five years later Tom More is breaking up the dirt in his garden. He has learned one of the desert fathers’ primary remedies for staving off acedia: work. Though all is not perfect—he is still occasionally visited by morning terrors, and liaisons with women are still a temptation—things are better. He wakes up early in the morning, hunts, runs a trotline, hoes the ground, and raises a family. He describes his new routine as “watching and waiting and thinking and working.” These are the earthy things that keep a person from spinning off into a pseudo-angelic orbit or sinking into the malaise of despair, things any desert father would endorse.

Percy would eventually overcome his own acedia and finish writing Lancelot, the darkest of his novels and to this day the least read. Although written under the influence of acedia, so to speak, Lancelot describes not so much the affliction’s own ambivalences as the nihilism to which it can lead. In the novel’s protagonist, Lance Lamar, acedia’s lethargy has given way to a blinding rage at the decadence of the modern world.

Percy maintained throughout his life that, “to the degree that a society has been overtaken by a sense of malaise, the vocation of the artist...can perhaps be said to come that much closer to that of the diagnostician.” The artist’s work, in other words, is not an autopsy but a diagnosis made in the hope of recovery—an attempt, he says, to “give the sickness a name, to render the unspeakable speakable.” Even when he is at his bleakest, Percy manages to counter despair with the possibility, however elusive, of hope. The fact that Lamar is speaking about—even confessing—his vengefulness and violence indicates as much; and the novel closes on the possibility of dialogical counterpoint, maybe even absolution. What will Percival the psychiatrist-priest say in response to Lancelot’s confession? The novel doesn’t tell us. But there are signs, even amid the darkness of Lancelot’s infernal vision, that Lamar could still move into the realm of contemplation. The question is whether we, the readers Percy is ultimately addressing, are able to recognize those signs.

Percy believed that the world is strewn with such signs, if only we are looking for them, and know where to look. It is all too easy to miss—or even blind ourselves to—the signs of the transcendent shot through the world of the everyday, and therefore to miss everything. But it is exactly in that world that we find Walker Percy, a voice in the wilderness crying out like a prophet, “He that hath ears to hear let him hear.”