Sociologists once took it for granted that religion would eventually disappear. According to sociologist of religion José Casanova, the so-called “secularization thesis”—that industrialization and advances in modern science were driving religion away—dominated the social sciences in the nineteenth century. The world was going through a process of “disenchantment,” as Max Weber put it; “God is dead,” Friedrich Nietzsche announced, “and we have killed him!”

The secularization thesis remained largely untested until sociologists like Peter L. Berger and Andrew Greeley began to scrutinize it in the 1960s. The data showed that religion was not so clearly in retreat after all—if anything, it was resurgent around the world. Berger thus began to speak of “desecularization” in the 1990s, and other sociologists began to refer to our society as “post-secular.”

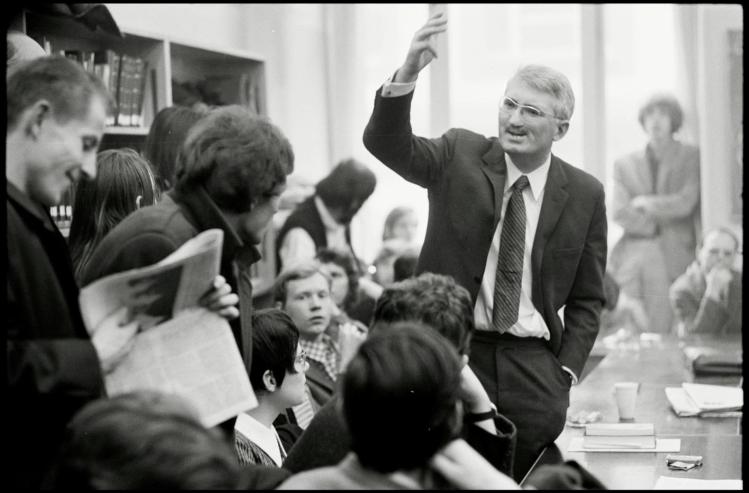

Many philosophers had also assumed that religion would eventually die out, including the prominent German social theorist Jürgen Habermas. That can hardly surprise readers who remember Habermas as the revisionary Marxist of the 1960s or who think of him, more recently, as a philosopher of communication and secular champion of rationalization. It’s striking, then, that such a thinker would eventually engage then-cardinal Joseph Ratzinger himself in dialogue, as Habermas did in 2004. It’s even more striking that he would come to emphasize the contemporary importance of a living Christian faith, grounded in the Eucharist. Habermas’s evolving thought on religion culminated in a massive 2019 monograph titled Auch eine Geschichte der Philosophie (the first two volumes of a three-volume English translation, Also a History of Philosophy, are now available).

Why this apparent reversal? How did Habermas come to his earnest interest in religion? And what might he have to offer to Catholics, with our long tradition of engaging the insights of philosophy in the service of articulating the faith?

Habermas ranks among the master philosophers of the twentieth century. Born in Düsseldorf in 1929, he came of age as the Second World War came to an end. As he explains in a short autobiographical essay, two experiences stoked his intellectual passions. As a child, he endured multiple surgeries to correct a cleft palate. The misunderstanding and rejection he experienced because of his impaired speech gave him a keen appreciation of the importance of communication in human life. The role of mutual understanding in society and political life would become the central theme of his life’s work.

The second influential experience occurred after the war, when, at age sixteen, Habermas followed the Nuremberg Trials and learned that the Nazi regime under which he grew up was “pathological and criminal.” After he took up university studies, he saw how badly German intellectuals had failed, many of them having supported National Socialism. Habermas was deeply disappointed with both German academic philosophy and the regime of West German chancellor Konrad Adenauer. Philosophers hadn’t developed the resources to effectively resist authoritarian ideology, while Adenauer failed to grasp the deep need in Germany for moral and political renewal.

In response to those deficits, Habermas, along with other philosophers of his generation, looked beyond Germany for conceptual resources and democratic models. He would eventually find what he was looking for in the American pragmatists Charles Sanders Peirce, John Dewey, and George Herbert Mead—with their communicative model of inquiry, emphasis on public deliberation, and interaction-centered analysis of the self.

The young Habermas also stuck his neck out, taking professional risks. Perhaps the most daring came in 1953, while he was still a graduate student but working on the side as a freelance journalist. In the prominent newspaper the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, he publicly challenged philosopher Martin Heidegger over his lack of repentance for his Nazi past. In a new publication of prewar lectures on metaphysics, Heidegger had retained, without comment or apology, a passage that praised National Socialism for its “inner truth and greatness.” In response, Habermas asked, “Is it not the foremost duty of thoughtful people to clarify the accountable deeds of the past and keep the knowledge of them awake?” Thus began his long record as a public intellectual in Germany—with a bang.

From the start, Habermas’s interests were insatiable. As a budding public intellectual, he wrote reviews and critical essays on subjects ranging from art, theater, and culture to philosophy, politics, sociology, bureaucracy, and technological society. As a student, he engaged the full gamut of German philosophy and beyond—including German Idealism, Marxism, phenomenology, existentialism, and philosophical anthropology. His circle of interlocutors would only continue to expand over the years.

It should therefore not surprise us that Habermas’s interests extended to religious thought early on, even though he lacked faith himself. Though raised Protestant, he often describes himself, using a phrase of Max Weber’s, as “religiously tone-deaf.” Still, even as a doctoral student, he grasped the significance of religious thought in the history of Western philosophy. He had a keen eye for philosophical “translations” of religious ideas—a motif that would assume considerable importance in his later thought.

In his 1954 dissertation on the German idealist philosopher Friedrich Schelling, Habermas traced Schelling’s treatment of creation as a “divine contraction” to Christian and Kabbalist sources. Schelling’s understanding of creation and the Fall would have lasting significance for Habermas, in particular for his conception of moral freedom. As he explained in an interview, divine self-limitation opens the space for an unconditionally free creature in whose eyes God’s own freedom is confirmed: “[The creation] myth—and it is more than just a myth—illuminates two aspects of human freedom: the intersubjective constitution of autonomy and the meaning of the self-binding of the will’s arbitrary freedom to unconditionally valid norms.” Habermas has moral autonomy in mind here: only through relationships of mutual recognition and care can we acquire the capacity to act on moral obligations—not as impositions from outside but as freely chosen dictates of our own conscience.

Habermas sees the influence of Christian and Jewish mysticism running through Schelling and Marx and into the nuanced, historically sensitive philosophy practiced by Jewish philosophers Ernst Bloch and Walter Benjamin. Bloch and Benjamin had influenced the circle of Jewish theorists working at the Institute for Social Research (Institut für Sozialforschung, IFS), a think tank affiliated with Goethe University Frankfurt and dedicated to rethinking Marxism. It was thus fortuitous that in 1956 Habermas accepted a position at the IFS as Theodor Adorno’s assistant, beginning his association with the “Frankfurt School,” as it would later be called. Its leading members all exhibited a strong interest in religion, colored by traces of Jewish messianism.

Habermas, however, focused on sociological research at IFS. His habilitation (a second major work required to gain a professorship in German academia), completed at the University of Marburg in 1961, continued in that vein, offering a social history of the public sphere as it emerged in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. That book, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, gained considerable attention in Germany, establishing him as an up-and-coming social theorist, well equipped for the interdisciplinary style of Frankfurt School critical theory when he returned there in 1964 as a full professor at the university.

The following decades would establish Habermas as a leading social philosopher and critical theorist. In his theoretical work, Habermas aimed above all to overcome deficits he saw in the humanistic Marxism of the Frankfurt School. Adorno and Max Horkheimer (IFS’s director) had worked themselves into a corner, according to Habermas. Having associated a destructive modern instrumentalist mindset with human reason itself, they could offer no convincing path forward for social theory. Habermas saw the source of their embarrassment in overly narrow conceptions of both reason and truth.

His attempts to overcome those deficits eventually led to his two-volume The Theory of Communicative Action (1981). In that work, Habermas analyzes communication as a kind of social action. Through successful communication, we build relationships based on forms of shared knowledge, which vary according to the kind of “validity claim” at stake. Besides factual knowledge of the external world, there is moral knowledge of what is right and wrong, reasonable trust in the sincerity of others as demonstrated by behavior, and self-knowledge or authenticity. In each of these dimensions, we can distinguish between claims that are based on good reasons or evidence and those that are not.

Habermas deployed this theory to construct a more robust model of democracy that went beyond Frankfurt School pessimism. Horkheimer and Adorno realized that Marx’s confidence in the proletariat as an agent of revolutionary change was no longer credible, but they were unable to credit democracy and the public as a whole as potential agents of change. Habermas definitively shifted the addressee of social critique from the working class to the democratic public. His insight into the connections between the ideals of reason (freedom, equality, justice, etc.) and language itself provided him with a basis for hope that constitutional democracy could drive positive social change.

During the 1970s, Habermas approached religion primarily through the sociological lens crafted by Émile Durkheim and Weber, two influential sources of the secularization paradigm. Drawing on Durkheim, Habermas essentially affirmed that paradigm in positing a modern “linguistification of the sacred,” according to which other discourses, in particular in law and secular morality, were gradually replacing religious rituals as the bond that holds society together.

But the secularism of Habermas’s systematic works clashes with other remarks on religion he made around the same time. In a 1978 talk honoring Gershom Scholem on his eightieth birthday, Habermas praised Scholem for his deep studies of Jewish mysticism. The conclusion of that talk anticipates Habermas’s later work: “Among modern societies,” he said, “only those who can bring essential elements of their religious tradition, which points beyond the merely human, into the spheres of the profane will be able to save the substance of the human as well.”

Habermas’s work on religion from 1988 onward essentially boils down to an explication of that thesis. That year, speaking at a conference on public theology at the University of Chicago Divinity School, he responded to Christian theologians who confronted him with the ongoing relevance of religious-theological contributions to public discourse. Later published under the title “Transcendence from Within, Transcendence in this World,” the talk reveals a significant evolution in Habermas’s thought on religion.

First of all, Habermas grants that his sociological treatment of religion had too hastily affirmed the secularization thesis. He had given an overly “one-sided, functionalistic description” that assumed religion would fade away to be replaced by other sources of value. Instead, social scientists and philosophers must leave open the question of the future prospects of religion and its ongoing relevance in secular society.

Secondly, Habermas now considers religious thought a form of discourse in its own right, oriented by claims about a transcendent reality. Though religious discourse “bases itself on the specifically religious experiences of the individual,” it takes place within a believing community of practice and, as he would later point out, cannot be reduced to matters of personal authenticity. At the level of religious practice, dogmas of faith are protected from critical questioning. But theological discourse—a distinct form of inquiry, alongside philosophy and the sciences—opens ritual practice and belief to interpretive inquiry and the demand for justification.

Finally, what counts as justification can differ among theologians and traditions. Habermas distinguishes three main strands. One path is exemplified by fideistic Protestant theologians, who rely on Scripture and faith as the privileged source of insight, independent of reason. A second, favored strand—exemplified by “enlightened Catholicism”—engages with secular thought and the sciences, albeit without invalidating the religious experiences articulated in the tradition, which form the basis for theological reflection. The third strand, a radically demythologizing theology close to secular philosophy, adopts a “methodological atheism” that detaches inquiry from any religious faith commitment.

Demythologization harbors a danger, Habermas warns. Theology “loses its identity” if it adopts scientific skepticism and merely “cites religious experiences” rather than acknowledging them as theology’s own authoritative basis. Here lies a challenge to theologians: they must remain faithful to the experiential and communal sources that feed their discourse and make it distinctive. Coming from a nonbeliever like Habermas, this admonition is surprising: Why would a thinker who once placidly accepted the secularization thesis now insist on the religious authenticity of theological discourse?

The answer lies in Habermas’s understanding of the hermeneutical task of theology and philosophy. Just as philosophy aims to interpret the common sense that underlies our everyday practices, so theology, as “faith seeking understanding,” interprets religious discourse as found in scriptures, rituals, and other practices. But the religious language on which theologians rely loses its vitality—and theology loses its distinctive contribution to public life—if it is not sustained by a living, communal practice of faith.

In subsequent decades, Habermas’s thoughts on religion developed further, reaching full fruition in Also a History of Philosophy, which recounts the discourse between faith and knowledge over three millennia. He presents that history as a genealogy, a reconstruction of the “collective learning processes” that led to the secular, “postmetaphysical” style of thinking so dominant today.

The first volume focuses primarily on the so-called “Axial Age,” a period between 800 and 300 BC when civilizations from the Far East to Greece gave birth to the great religions and systems of cosmological thought. In those cultures, narrative myths gave way to comprehensive world-views that explained everyday appearances in terms of deeper essences and abstract theories of being. Particularly important for Habermas was the spread of universalistic conceptions of humanity and morality, expressed, for example, in forms of the Golden Rule found across all major religions. It is in the Axial Age that Western philosophy and theology are born together, sisters springing from the union of “Athens and Jerusalem,” Greek philosophy and the Judaic tradition.

In general, ancient and medieval metaphysical systems of thought like Aquinas’s elaborated comprehensive theories of being from a God’s-eye point of view, presuming that the categories of everyday thought must align with ultimate structures of being as such. But with the Copernican Revolution and rise of the empirical, mathematical sciences, those worldviews gradually lost their plausibility. They were also discredited by technological developments, growing societal complexity, and religious and political conflicts. Philosophy instead began to see itself as historically conditioned, fallible, and subordinate, in many cases, to the special expertise of other disciplines.

Yet philosophy still has an important contribution to make. Habermas regards David Hume and Immanuel Kant as key figures here, offering two different visions for philosophy in the modern age. In Hume, Habermas sees the progenitor of a philosophy prone to scientism: it looks at human existence from the outside, as it were, reducing human experience to objective physical and psychological processes. Kant, by contrast, remains committed to humanism and the enduring questions about the meaning of human life that trouble our self-understanding: What can I know? How ought I to act? What may I hope? What is a human being?

Moreover, rather than skeptically dismissing religion as irrational, Kant sees it as a rich source of philosophical ideas such as human dignity, moral autonomy, and universal solidarity. Hegel develops Kant’s method by grounding these concepts in their history, but at the same time reduces history to the preordained unfolding of absolute reason or spirit (Geist), thereby negating the genuine contingency of historical development. According to Habermas, it is only with post-Hegelian thinkers such as Søren Kierkegaard, Marx, and Peirce that postmetaphysical thought fully emerges. Habermas regards his own philosophy as another step on this humanistic path.

Philosopher Amy Allen has described Habermas’s genealogy as “vindicatory” insofar as it defends Enlightenment values as the outcome of collective learning processes. It thus stands in sharp contrast to the “nostalgic” histories of decline that one finds in thinkers like Heidegger. Rather, Habermas’s positive view of modernity is closer to that of Charles Taylor, who affirms the modern emphasis on human rights, equality, and freedom. To be sure, modernity has its dark side and its inconsistencies, as critics of Habermas have pointed out. But to defend modernity as one stage in an ongoing learning process is not to affirm these imperfections—for example, Kant’s disparagement of women and non-Europeans. Indeed, his genealogy provides a basis for hope for further moral progress.

In framing the learning process as the result of a discourse between faith and knowledge, Habermas does not mean that faith is not a kind of knowledge. His 1988 talk implies just the opposite: religious beliefs qualify as a kind of knowledge that has authority for a specific community and is fed by their religious experiences and practices. Collective learning processes, by contrast, yield a wider public knowledge.

The natural sciences offer the clearest examples of public knowledge, but moral and practical life also produce public knowledge in the form, for example, of democratic institutions and constitutional rights. Because these result from collective learning in governance over complex societies, they deserve acceptance, with a proviso for their ongoing improvement. Postmetaphysical philosophy does not exactly figure in this picture as public knowledge. Rather, it offers publicly understandable, but contestable, interpretations of the implications of public knowledge for human life and experience, without relying on the religious commitments particular to individual communities.

Though Habermas defends secular modernity, his book also marks a crucial corrective against a tendency toward self-deception in modern thought. “The blinkered enlightenment...unenlightened about itself” too often dismisses religion as a relic of a supposedly unenlightened past. Contrary to the secularization thesis, religion remains an active participant in secular societies—for better and worse. Secular rationalists will understand themselves only if they clarify the relationship between reason and religion through open dialogue with believers, in which both sides work together to identify yet-untapped resources in religion that can be translated into a postmetaphysical, secular idiom.

Naturally, Habermas does not expect such translations to preserve the full meaning of religious convictions. Rather, he seems to have in mind translations that can expand the moral sensibility of secular citizens. Such translations become especially important in pluralistic constitutional democracies. Democratic outcomes will be broadly legitimate only if citizens, religious and nonreligious, can construct a common language that can serve as the idiom of public legal justification. Without being overtly religious, this language would offer a universal way of talking about the moral consequences of politics and policy.

Behind Habermas’s entire philosophy lies a central “motivating thought.” As he explained in a 1981 interview, his work concerns the reconciliation of a modernity that has fallen apart, the idea that without surrendering the differentiation that modernity has made possible in the cultural, social and economic spheres, one can find forms of living together in which autonomy and dependency can truly enter into a non-antagonistic relation, that one can walk tall in a collectivity that does not have the dubious quality of backward-looking substantial forms of community.

Habermas’s genealogy reveals a growing concern that secular modernity, which is “threatening to spin out of control,” still needs its sister religion, perhaps now more than ever.

To understand why, we must look to the role of hope, both secular and religious, in Habermas’s model of reconciliation. Habermas envisions a cosmopolitan legal order—not a total world government but rather a structure similar to the United Nations, only with a deeper commitment to human rights, stronger powers of conflict resolution, and more effective venues for international cooperation. The crises we confront today—environmental, financial, technological, humanitarian—are global in scope and cannot be mastered at the national level. Running through Habermas’s genealogy is the hope that such a cosmopolitan constitutional order will someday arise, based on principles of international justice which all nations freely adopt.

Enacting that vision depends on dialogue and social movements that cut across cultures. But how to build such movements, which involve significant costs for their participants? Secular morality, separated from religious belief and communal practices, loses much of its motivating power. Focused on individual conscience, it “does not foster any impulse towards solidarity, that is, towards morally guided, collective action.” The consequent lack of solidarity, Habermas fears, breeds a “defeatism lurking within” reason—specifically, a lack of the hope and courage necessary to motivate risky collective action for a more just society.

Habermas offers his genealogy in response to that defeatism. By reconstructing the learning processes that produced democratic institutions and human-rights charters, he aims to provide grounds for secular hope based on the recognition that change is possible because it is already underway.

But secular hope may not be enough. Religion enjoys a motivational advantage: “Religious consciousness...preserves an essential connection to the ongoing practice of life within a community.” Thus, “the religious consciousness of the individual can derive stronger impulses towards action in solidarity, even from a purely moral point of view, from this universalistic communitarianism.” But religions, of course, come with their own baggage. Especially in their fundamentalist versions, they have a checkered historical track record and have been a source of conflict as much as solidarity. Habermas believes that the prospects for a cosmopolitan order of law depend on world religions mastering the demands of dialogue and cooperation based on mutual respect for other religions and for nonbelievers.

The discourse between faith and reason in the West already shows that Christianity can take up that challenge. Can non-Western religions do so? Only an analogous discourse in those cultures can answer that question. Habermas thinks that his overview of Axial Age cultures provides at least some grounds for a positive answer.

What Habermas has to offer Christians, then—and Catholics in particular—is first of all a challenge. We must take up the task of translating our religious beliefs into an idiom that clarifies for nonbelievers the secular moral and political import of those beliefs. In that challenge lies a call to discernment: In light of today’s global challenges, what religious sources of motivating hope will, once translated, best move nonbelievers to solidarity and action? We can understand that task, I propose, as a kind of evangelization in pluralistic, secular societies. In The Joy of the Gospel, Pope Francis is quite clear that cross-cultural dialogues—not unlike the kind Habermas describes—qualify as works of evangelization for Catholics.

The gospels of Matthew and Luke offer an apt image of this form of evangelization: they compare the Kingdom of God to a woman working leaven into a mound of dough, causing it to rise. The leaven of dialogue aims first of all at creating the mutual understanding and trust that can link believers and nonbelievers in the joint service of a good and just society.

Using a different metaphor, Habermas refers to religious faith as a “thorn in the flesh of modernity,” prodding it, through dialogue and translation, to look beyond itself. But believers can serve as effective agitators only on the basis of their communal ritual practices, such as the Eucharistic Meal, which concretely embody the Christian claim to strong transcendence. Without such rituals, Christianity would lose its distinctively religious character and social relevance. The concern that Habermas expressed in 1988 for the authenticity of theology here reveals a deeper basis—the need for authentic Christian witness as an element of a fruitful dialogue between faith and reason.

Of course, this requires that nonbelievers abandon a hostile attitude that dismisses religious belief. They must instead grant “that religious convictions have an epistemological status that is not purely and simply irrational,” as Habermas put it in his exchange with Cardinal Ratzinger.

Believers bear significant burdens, too. Some Christians complain about the work of translation, but if translation is conceived of as evangelizing, these complaints are unbecoming. After all, our faith calls on us to spend ourselves in spreading the Good News. Today that task surely includes building mutual trust with nonbelievers and working together for a world of peace and justice.

Moreover, believers must accept public dialogue as authoritative in certifying principles of international justice. This demand is surely a difficult one for many Christians and their leaders. Within the Catholic Church, popes and bishops have long turned to natural law as an accessible language for addressing the public beyond the Church. But do they grasp the full implications of using natural law as a means of translating religious beliefs into secular terms? If its moral truths are accessible to “natural reason,” then they are open to contestation by reasonable audiences—many of which, today, are committed to postmetaphysical thinking. Are Church leaders willing to engage in dialogue on these terms? It remains an open question.

Even if the Catholic Church is unable to cede this much ground, participation in such dialogue remains important and potentially fruitful. We cannot predict on the basis of present social mores how coming changes in the social, political, and ecological context may shift the contours of discussion. Nor can we predict how the contributions of non-Western cultures and religions might affect the terms of the dialogue. For that dialogue to succeed, Christians must be willing to work their leaven through the dough—no matter how messy it may be—in the hope that it will rise.