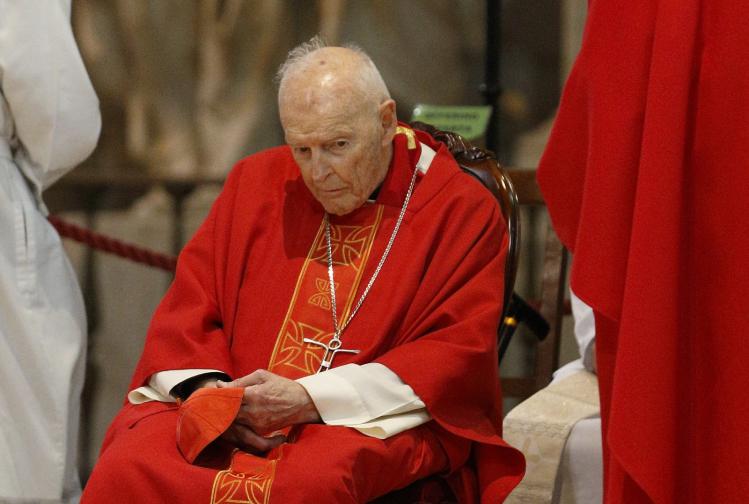

In the weeks since reports of Cardinal Theodore McCarrick’s sexual abuse of seminarians and minors began to appear, there has been a chorus of cries for an investigation—not just into how the incidents of abuse took place, but also into how McCarrick advanced in the hierarchy despite them. The investigation must find the culprits who, knowing McCarrick’s misdeeds, were responsible for his ecclesiastical advancement.

USCCB president Archbishop Daniel DiNardo raised the prospect of an investigation in a statement immediately after the scandal broke, saying “We are determined to find the truth of this matter.” Cardinal Donald Wuerl of Washington DC recommended a church probe staffed by bishops. Bishop Edward Scharfenberger of Albany called for “an independent commission led by well-respected, faithful lay leaders.” Bishop Robert Barron of Los Angeles took up the cry at his Word on Fire blog, saying that we must learn “what the responsible parties know, and when did they know it” even as he put the ultimate blame on the devil. A group of young conservative Catholic academics and writers, in an open letter published at First Things, angrily insisted on an investigation as well.

The scope of such an investigation is sometimes described in narrow terms, focusing solely on how McCarrick got promoted. In other instances, a broader inquiry is envisioned, including a probe into why his successors in Metuchen and Newark kept payouts to adult survivors of McCarrick’s abuse a secret. But in every case the demand is to identify the people who failed to stop him. The expected result is a return to a state of justice, once these individuals are named and censured (though who would censure them and in what way is unclear). Permit me to observe that these responses are typical of American confidence in legal and penal solutions to injustice. They are also likely to fail.

There are several reasons why. First of all, what will the people calling for these investigations do if Pope Saint John Paul II is implicated? He is likely implicated, after all. He gave McCarrick the red hat. He signed off on his advancement. John Paul knew that Marcial Maciel Degollado, founder of the Legionaries of Christ, had numerous accusations against him, yet he supported him to the end. He may well have known about McCarrick too. Yet the Polish pope, who many call “great,” is now canonized and has a place in the calendar of saints. How much do you want to bet that any official church investigation—no matter who conducts it—will be circumscribed in such a way that it cannot impugn his memory? Yet if it cannot reach the top, it cannot satisfy the demand for truth.

Second, in order to discover who is responsible for the McCarrick mess, an investigation would have to find out and make public the workings of the Congregation of Bishops that were responsible for his advancement. It would need to report on the machinations that went on behind the scenes at that curial institution. This is plainly impossible. No American committee, even one comprised of bishops, can conduct a forensic investigation into that body. It is out of our reach.

Third, to be fair, any investigation of how the McCarrick scandal came about would also have to acknowledge the widespread practice of “winking” at the misdeeds of the ordained—a practice so common that it may fairly be said to be a feature of clerical culture. Winking means looking the other way, or passing off with a joke, anything that uncomfortably hints at malfeasance. Truth demands that we take this phenomenon into account. But can winking even be investigated? Once you start lining up everybody who laughed something off, or didn’t want to get involved, or looked the other way rather than confronting a powerful man who did unethical things, you certainly do “find the truth of this matter”—but unfortunately it’s this: the flourishing of McCarrick’s career despite his crimes is the result of a systemic problem.

Systemic problems cannot be cured by finding culprits. They require systemic solutions. This fact should sharpen our wits rather than discourage or defeat us. The cover up of abuse and the concomitant enabling of abusers, after all, is a phenomenon we already understand fairly well in the church. It arises from a confluence of factors: the insularity of clerical culture, the willingness of clerics to lie to protect one another, and the corrosion of moral integrity when motives of faith and mission give way to concerns about advancement, power, privilege, and maintaining insider status.

So what can be done? The good news is that there is an alternative to a convict-and-punish response to the scandal. Rather than embarking on a lengthy, frustrating, and probably fruitless search for justice through identifying culprits in the McCarrick case, the American bishops can immediately begin to address the systemic issues embodied in that scandal. The first thing the American church must do—and probably the only effective thing it can do—is to put its own house in order.

In order to do this, the bishops will need to work together with all the members of the church. They cannot address the problem alone. But it’s altogether possible that clergy and laity can do it together by recognizing the crisis for what it is and applying remedies with rigorous care.

Just as the American church established training in how to maintain safe environments for children and youth, it can start in on the work of putting everyone on notice concerning the problem of winking at illicit clerical sexual activity with adults, as well as financial malfeasance, misuse of power, corruption of conscience, and all the rest. Protocols can be put in place to protect whistleblowers and to see that accusations are taken seriously. Training in seminaries and houses of religious studies can support these initiatives. Efforts that have already been made to safeguard minors can be enlarged to include adult victims. Our national and local guidelines to prevent abuse can and must be rewritten to apply also to bishops. Prospective bishops should be locally screened for credible abuse allegations before their names are sent to Rome. Ultimately, the insularity of the clerical system, an insularity currently fostered in seminaries, needs to give way to a greater imperative: the good of the Catholic community as a whole.

There is also a spiritual dimension to this crisis that is waiting to be addressed. We need to renew a humble, Christ-like sense of mission in the American church across the board. I haven’t always been happy with how Pope Francis handled the problem of sex abuse in Chile, which is the case that he has dealt with most closely. He was slow to accept facts on the ground that seemed obvious to the public (96 percent of Chileans believe that the church hid and protected priests accused of sexual abuse, according to a recent survey), and to date he has not censured a number of bishops who seem implicated in the scandal. But he did get at least one thing right. When he met with the Chilean bishops, he called on them to rediscover their mission by remembering their calling “not to be served but to serve.” He told them that the church thrives by renouncing privileges, not by cultivating elitism. He recalled that the church in Chile used to be prophetic, and asked them to return to their roots. In other words, he saw with laser clarity that the only way out of this crisis is to follow Christ’s example and take on the gentle yoke of his humility.

We could use a dose of that insight in the American church right now. For better or worse, most of our bishops are canon lawyers; it will be easy for them to assume that the most effective means at their disposal for dealing with this crisis are investigative tools and legal remedies. They aren’t. Just as the church can’t restore trust and credibility through a forensic investigation of McCarrick’s misdeeds, it can’t cure the systemic problems of clerical abuse by anything less than a conversion.