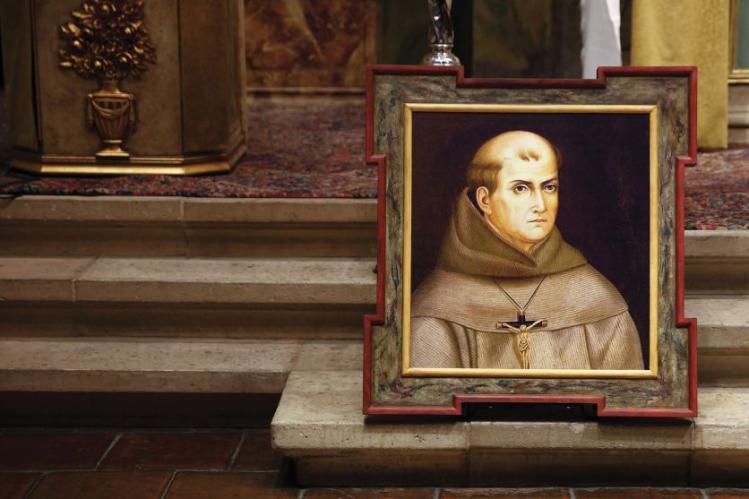

In 1988, John Paul II beatified Junípero Serra (1713–1784), the Franciscan friar who founded California. Given the treatment of Native Americans under colonialism, some have questioned Serra’s prospective sainthood. On an episode of Firing Line in 1989, William F. Buckley Jr. hosted a discussion of the merits of the case. The exchange was predictably lively. One guest was Edward Castillo, a Cahuilla-Luiseño professor of Native American Studies at Sonoma State University, and a Serra critic. The other, Fr. Noel Moholy, was vice-postulator for the Serra cause. Buckley began by asking Castillo if he was “protesting the canonization of Junípero Serra in your capacity as a Christian or merely in your capacity as a Californian, or both?” Castillo, who had participated in the Indian occupation of Alcatraz Island in 1969, declared himself “a pagan.” To which Buckley responded, “But as the lawyers put it, you really have no standing, do you? That is to say, it’s none of your business who the church canonizes.”

Noel Moholy, who must have watched that exchange with a mixture of apprehension and bemusement, put it succinctly: “Now, the question before the house is not canonizing the mission system. The question is about this individual: What kind of life did he lead?”

To some, that complicated and arduous life seems beside the point. Last January, shortly after Pope Francis’s surprising announcement that he would canonize Serra during his visit to the United States this month, a statue of Christ in a cemetery at Mission San Gabriel in Los Angeles was toppled, its head and arms removed, and a cross smashed at another grave. A MoveOn.org petition, which is supposedly signed by “descendants of California mission Indians,” seeks to “enlighten” the pope about “the deception, exploitation, oppression, enslavement, and genocide” of California natives. And that’s just for starters.

Yet José Gómez, the archbishop of Los Angeles, sees Serra as an ally of those who defended the indigenous peoples against Spain’s early violence, but with a difference. “Fr. Serra never delivered fiery sermons like [Antonio] de Montesinos,” Gómez says. “He never engaged in theological and moral debates in the royal courts, as [Bartolomé] las Casas did. One way to think about him is that he was kind of a ‘working class’ missionary—a guy who tried to get things done.”

So who, exactly, was Fr. Junípero Serra? Why are some people angry about his canonization? And finally, why did Pope Francis take a stalled sainthood case, dispense with the need for a second miracle, and not only make Serra the first Hispanic saint in the United States (and the first who worked primarily in the American West), but make himself the first pope to canonize a saint on U.S. soil? (The canonization will take place on September 23 at the Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C.).

Serra is virtually a household name in California, where all fourth-graders are required to study him and the missions. Mention his name in the East, however, and people usually draw a blank. This may have something to do with the Anglocentric narrative told about the birth of this country. But the Spaniards were here first, by almost a century.

Junípero was born Miguel José Serre on the island of Mallorca off the northeast coast of Spain. Taking the name of St. Francis’s sidekick, Miguel became a Franciscan priest as Junípero. Like many Franciscans, he was a disciplinarian and a vigorous practitioner of self-mortification. He was also an accomplished academic, rising to a chair in theology at Mallorca’s Llullian University. Discerning a vocation to missionary work in middle age, he arrived in the New World in 1749. On a legendary first walk—from Veracruz to Mexico City—he was bitten by a venomous spider that caused him leg pain for the rest of his life. Before being sent to California, he spent eighteen years toiling with the Pames Indians in the Sierra Gorda of Mexico, and on missionary trips almost as far south as the Yucatan. Then in 1768 he was sent to Baja California, and the following year into what is now the state of California. The Spanish monarchy was eager to protect its trade routes between the Philippines and Mexico by securing California’s harbors from the encroaching Russians in the north. But Serra was eager for souls. Over the next fifteen years, he founded nine of twenty-one missions along the Pacific coast. He baptized or confirmed six thousand Indians himself (over eighty thousand California Indians were ultimately baptized by the early Franciscans), dying at Carmel, his home mission, in 1784.

Six hundred Indians were said to have wept at Serra’s funeral, piling his bier high with wildflowers. Perhaps this is not surprising, for Serra could be a fierce critic of the Spanish colonists and a staunch defender of the Indians. Writing to the Spanish viceroy in Mexico City demanding the removal of a military commander, he was graphic in his outrage: “The soldiers, clever as they are at lassoing cows and mules, catch an Indian with their lassos to become prey for their unbridled lust. At times some Indian men would try and defend their wives, only to be shot down with bullets.”

Contrary to some contemporary claims, the testimonies gathered sixty-six years ago in making the case for Serra’s sainthood give unmistakable, consistent, and concrete evidence of Indian reverence toward the Franciscan. The current debate, suggests Fr. Henry Sands, a Native American and director of the U.S. bishops’ Secretariat for Cultural Diversity, is filled with “overblown and incorrect” information about Serra’s character and life. To be sure, given the tragedy that engulfed the native population after the arrival of the Spaniards and then the Anglos, skepticism about the motives and actions of missionaries like Serra is warranted. “There is so much that has been done in the past, and to the present day, that is wrong,” said Sands at a 2015 conference on America’s “Founding Padres.” But Serra, although implicated in that tragedy, was never an advocate or a perpetrator of those crimes.

PERHAPS A BRIEF summary of what happened to the Indians of the Americas is in order. What one historian has called the first “world war” is also certainly the original sin of the nation. No Catholic, no Christian, can explain it away.

During the French and Indian War of the 1760s, the British officer Sir Jeffrey Amherst suggested to his officers that they “Inoculate the Indians [with smallpox] by means of Blankets, as well as to Try Every Other Method, that can serve to Extirpate this Execrable Race.” In 1763, at Ft. Pitt (today’s Pittsburgh), a fellow named William Trent gave “two Blankets and a Handkerchief out of the Smallpox Hospital” to two Delaware Indians. Soon the Delaware were overwhelmed by smallpox. In the following century at least forty smallpox and measles epidemics would ravage the native population.

Although disease was responsible for the vast majority of Indian deaths, American violence was pervasive as well. Some of the most egregious incidents are well known, often tied to prospecting for gold. At Sand Creek during the Colorado gold rush of 1859, Col. John Chivington bragged of killing five hundred Cheyenne Indians. At Wounded Knee in 1889, three hundred Indians, mostly women and children, were massacred by U.S. troops and dumped into a ditch. During the Modoc War of 1872, the last stand for California’s native peoples after the gold rush, white Americans briskly pursued the goal announced by Peter Burnett, the state’s first governor: “It is inevitable the Indian must go.”

By the time Nez Perce Chief Joseph (“I will fight no more forever”) died in 1904 of what the reservation doctor called “a broken heart,” the population of Indians in the United States was about 250,000. If we accept historian William E. Denevan’s estimate that there were 3.8 million natives in what is now the United States and Canada when the Europeans arrived on the continent, that makes a decline of 93 percent (see Denevan’s The Native American Population of the Americas in 1492).

There is no evidence that Serra was complicit in any such crimes. Quite the contrary. The Kumeyaay attacked the San Diego mission in 1775, killing three Spaniards, including one of Serra’s closest associates. As the imprisoned rebels waited to be hanged, Serra called for pardon: “As to the killer, let him live so that he can be saved, for that is the purpose of our coming here and its sole justification.” (In fact, Serra said that even if he himself were killed, no one should be arrested.)

Indeed, Serra seemed to sense the inevitability, if not the justice, of the Kumeyaay’s revolt. He often spoke of the Indians being en su tierra (in their country). Yet isolating the Spanish colonists was not the answer. When the local military commander had the Tongva of San Gabriel erect the very stockade walls that would shut them out, Serra asked, “If we are not allowed to be in touch with these gentiles, what business have we…in such a place?”

Beyond this missionary imperative, there is another distinction to be made between the Spanish and the Anglo colonists. As historian David Weber has noted, by the 1790s in Spanish America, “numerous indigenous peoples had been incorporated rather than eliminated.” Spanish and Indian intermarriage was commonplace, whereas such mingling was anathema to most Anglos. Moreover, in California under Spain there were no large-scale massacres—nothing like Wounded Knee or the slaughter of the Modocs. True, the pre-contact population of California (225,000) had been reduced by 33 percent during Spanish and Mexican rule, but that was caused mostly by epidemics. Under American rule (from 1848 on), when most of the twenty-one missions were in ruins, the loss of indigenous lives was catastrophic—80 percent died, leaving just 30,000 in 1870. And nearly half of those losses were due not to disease, but to murder.

Despite this exculpatory history, three accusations have been made against Serra and the missions that need to be answered: that they perpetrated genocide; that they enslaved Indians; and that their treatment of Indians was cruel.

What the Americans did in all but extirpating Indians from the continent was genocide. What the Spanish did, at least in California, was not. This important distinction was acknowledged by two distinguished historians at a California Indian Conference in 2010. The Spanish had no intention of expelling the Indian population, according to James Sandos (Converting California) and George Harwood Philips (Vineyards and Vaqueros). The missions were designed to attract Indians, not destroy them.

The slavery accusation has its roots in misunderstanding or ignorance of how the missions worked. No Indian was forced to enter a mission, at least in Serra’s time. For a native population undergoing a disorienting invasion, the missions offered considerable enticements: food, clothing, shelter, the beauty of the churches, and the transfixing (sometimes fearful) display of Spanish power. Fr. Pedro Font, diarist of the second settler expedition into Upper California (1775–1776), observed, “The method of which the fathers observe in the conversion [of the Indians] is not to oblige anyone to become Christian, admitting only those who voluntarily offer themselves for baptism.” Historians confirm the accuracy of Font’s statement.

But there was a catch. Once one entered the mission, one was forbidden to leave without permission, and those who did—unless they voluntarily returned—were punished. (Indians typically were given leave for weeks or months to visit their villages, and in some instances, such as at Mission San Luis Rey, Indians stayed in their villages and the mission served as a kind of parish church.) But the survival of the missions was never a sure thing, and Indian labor (“spiritual debt peonage,” as Sandos puts it) was depended on by all. Indians were hunted down and lashed for leaving. It is estimated that the desertion rate was about 10 percent. Yet it is also important to keep in mind that the majority of California Indians never came into the missions in the first place, nor were they forced to—a fact critics often forget.

Of course, if 10 percent were fleeing, 90 percent were staying. Was it from fear? From a sense of defeat or disorientation? Or did those who stayed do so because the missions provided what seemed a stable community in a frequently perilous world? Serra may have felt himself to have landed in Eden at first, but perhaps not all Indians did. True, California tribes had their own sustaining faith systems, mastery in art, pottery, and canoe-building, and great skills in hunting, fishing, and gathering. Still, just as it is today, eighteenth-century California was subject to severe drought. Outside the missions, tribal rivalries could result in bloodshed. Women were bought and sold. A shaman could target you with vengeance. Life in the missions with its food and shelter, its art and music and gospel of love, may have appealed to a not insignificant number of native peoples, despite onerous punishment.

Were Indians flogged? Yes, for theft, assault, concubinage, and desertion. Corporal punishment was of course routine at the time in European and most other cultures, though strange to California Indians (some tribes subjected prisoners-of-war to a gauntlet of thrashings). Did that make it right? Of course not. It was wrong. However, nothing in the record suggests that Serra was a cruel or vindictive overlord. “We have all come here and remained here for the sole purpose of [the Indians’] well-being and salvation,” he wrote. “And I believe everyone realizes we love them.” Unlike many of his co-religionists, Serra almost never referred to Indians as savages or barbarians; though at times he’d say infieles, most often he called them gentiles or pobres or simply indios. He boldly questioned the Spanish governor’s application of the phrase gente de razón (people of reason) solely to Spaniards. Clearly, Serra thought he was bringing salvation to people of equal dignity.

Part of the current puzzlement and anger over the Serra canonization is motivated by an entirely justified revulsion over the historic crimes committed against the Indians. Until the past few decades, American culture was largely indifferent to those crimes, and portrayed the victims as savages. Serra figured as a character in the 1955 film Seven Cities of Gold, which, according the New York Times, involved “acrobatic Indians as painted and feathered demons.” Good riddance to all that. We must put away the caricatures of Hollywood, and come to terms with the real history—the near extermination—of Native Americans at the hands of white Americans. But if that is the case, I think an understanding of the real Serra is just as essential.

The historical record tells us that Serra was neither the perfect man the pious long for nor the vicious conquistador others imagine him to have been. In seeking reconciliation, can a real Serra and real Native Americans speak to each other across the centuries? Isn’t this what Pope Francis called for in his remarks about the sins of Spanish colonialism during his visit to Bolivia in July? “I also would like us to recognize the priests and bishops who strongly opposed the logic of the sword with the strength of the cross,” he said. “There was sin. There was sin, and in abundance, and for this we ask forgiveness. But…where there was sin, where there was abundant sin, grace abounded, through these men who defended the justice of the native peoples.”

THERE HAVE BEEN have been moments of real grace in the battle over Serra’s canonization. Consider two protest moments at Carmel, separated by thirty years. In 1987, Sr. Boniface, the nun whose cure had elevated Serra to beatification, “greeted and embraced” protesting Native Americans at Mission Carmel. Her fellow sisters were welcomed into the prayer circle of the protesters. Chumash leader Cheqweesh Auh-Ho-Oh was sitting off to the side with her eyes closed. Sr. Carolyn Mruz recalls touching her on the shoulder and saying, “Peace, sister.” At first, the Indian woman did not respond, but then her eyes fluttered open, and she said, “You are the first member of the church to approach me in peace. I knew it was a woman. And I knew it would be a religious sister.”

This year, during an Easter protest over Serra’s canonization, Fr. Paul Murphy emerged after saying Mass to welcome the protesters to Mission Carmel. He asked them to come at any time and state their needs. “I see Mission Carmel as a place of healing,” he said. “We all need healing.” Former Esselen tribal chief Rudy Rosales, who had attended the Mass, also spoke to the protesters. Though some local Indians grumbled that their cemetery was being violated by outside tribes participating in the protest, the fifty protesters dispersed peacefully—partly, some thought, because of the presence of so many children at Easter.

Archaeologist Ruben Mendoza—of both Yaqui Indian and Hispanic descent—was impressed by the peacefulness of the demonstration. His father had hated the church and the missions. When in fourth grade, Mendoza refused to do his required history project on the Franciscans (instead he built a model of a dinosaur). In high school, he fashioned Aztec pyramids out of stone and took an Aztec name: Tezcatlipoca. “I became obsessed with ‘pure’ Indian cultures,” he remembered. He carried this obsession into graduate school at the University of Arizona, where he studied under Vine Deloria Jr., the celebrated author of Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto.

Three “transformative” experiences, however, brought Mendoza to a new understanding of California history. The first was an invitation from the Mexican government to excavate a sixteenth-century convent in Puebla. There Christian and Spanish artifacts were mixed with Aztec ceramics and mosaics that showed “an incredibly diverse mass of humanity,” Mendoza said. The idea of a “pure” culture—Indian or otherwise—came to seem illusory. Mendoza himself is a mixture. A second revelatory moment occurred when, excavating at the San Carlos Cathedral in Monterey, he discovered the earliest chapel used by Serra in 1770. “After years of rejecting the California mission era, I felt a powerful personal connection with it,” he said. “I’m Iberian, indigenous, and Mexican. It took years to reconcile those differences.”

Finally, during the 2000 winter solstice, Mendoza witnessed the dawn sunlight flood into Mission San Juan Bautista. Investigating other missions, he identified thirteen “precisely oriented…to capture illuminations, some on days that would have been sacred to Native Americans.” Might the Franciscans have gone out of their way to show respect for Indian traditions?

What is happening now, one hopes, is the complementary emergence of an ethic of apology in the church over the sins of colonialism and of Indian representatives who are willing to take another look at the complexity of the encounter between the Franciscans and native peoples. This gradual convergence, demonstrating good faith on both sides of the issue, has been underway for some time. “If you take a look at the accomplishments of Serra, there has to be recognition,” Jerry Nieblas, an Acjachemen leader at San Juan Capistrano told me in 2010. “But I don’t want Franciscans to be too proud.” The Ohlone-Patwin Andrew Galvan, the only Indian curator of a California mission (San Francisco Dolores), puts it well: “The bottom line is my belief that Junípero Serra was a very good person in a very bad situation.” California Indian leader Galvan and his Mexican Indian counterpart Mendoza agree on sainthood. Says Mendoza, “I’ve always felt the canonization process was stymied through misinformation and politicization, and laying blame and onus on one individual who was actually in constant conflict with governors and military commanders in New Spain over how they were treating Indians.” On August 11, 2013, Ernestine de Soto—a Chumash shaman and registered nurse—prayed to a relic of Serra from Mission Santa Barbara and witnessed the apparently miraculous recovery of her daughter from a deathbed case of cryptogenic pneumonia. It was the first contemporary miracle attributed to Serra by a Native American. But now, because of Pope Francis, another miracle is no longer necessary.

WHY DID POPE FRANCIS pick Serra? Why did he dust off an old candidacy lost in centuries of controversy, and put it in the spotlight? And why would he choose to celebrate Serra in the seat of American power—Washington, D.C.?

I think there are several reasons. First, Francis finds in Serra a powerful kindred soul, an echo of his own love of the simple, the humble, and service to the poor. He sees Serra as a saint for our anxious times, and canonizing him in Washington rather than California implicitly marks him as a national, and even transnational, saint of the Americas. Francis dispensed with the need for a second miracle in part because he felt Serra’s spiritual qualifications and missionary work were so compelling.

I suspect that Francis also admires Junípero’s courage to speak truth to power. After all, the pope himself has taken on the Curia, the Vatican Bank, Wall Street, as well as those who would deny global warming or the injustice of abortion.

In a one-day Vatican conference on the Californian Franciscan in May, Francis cited “missionary zeal” as the first of the three “key aspects” of Serra’s life (the others are his devotion to Mary and “witness of holiness”). “What made Friar Junípero leave his home and country, his family, university chair, and Franciscan community in Mallorca to go to the ends of the earth?” Francis asked during Mass at the Pontifical North American College. “Certainly it was the desire to proclaim the Gospel ad gentes, that heartfelt impulse which seeks to share with those farthest away the gift of encountering Christ.”

Notice that Francis identifies Serra’s faith with the heart. Faith is a function of the heart as far as this pope is concerned. “Such zeal excites us, it challenges us!” the pope proclaimed. Admitting that it’s important to “thoughtfully examine [the missionaries’] strengths and, above all, their weaknesses and shortcomings,” Francis still found Serra to be a saintly man and true disciple of Christ. “I wonder if today we are able to respond with the same generosity and courage to the call of God,” especially to those “who have not known Christ and, therefore, have not experienced the embrace of his mercy,” the pope said.

Of his “shortcomings” over public silence concerning the depredations of the Argentine junta in the 1970s, Francis has spoken eloquently of his own need for mercy; he may see a mirror of his attempt to do good in extraordinarily difficult, dangerous times in Serra’s own life.

Finally, Serra’s attention to, and reverence for, the natural world resonates with Francis’s new environmental encyclical, Laudato si’. The title of that encyclical is borrowed from St. Francis’s “Canticle of the Sun,” with its refrain of “praised be” (“Praised be You, my Lord, through Brother Wind…. Praised be You, My Lord, for Sister Water.”) Serra’s detailed observations about the trees and plants he found in California end with the same praise for their Creator: “I have in front of me a cutting from a rose-tree with three roses in bloom, others opening out, and more than six unpetaled: blessed be He who created them!” Serra also demonstrated great respect—remarkable at the time—for Indian watering holes. Coming across “good, sweet water,” he insisted that the Spaniards and their animals not drink it: “We do not want to spoil the watering site for the poor gentiles.” In short, Serra was a Franciscan who truly lived up to the spirit of St. Francis, a spirit also embodied by the first pope to use that name.

In canonizing Serra, Francis “seizes the day” of the Hispanic ascension in North America. Many Americans think of this demographic change as an “invasion.” Francis has come to remind Americans who was here first—and not just physically, but spiritually. And who, indeed, is here now. This is not an attempt to erase original Indian life from the church’s memory, but a deeply respectful acknowledgement of it, because it was that life that Serra served up to the moment of his death. As the essayist Richard Rodriguez has suggested, the Mestizo—the melding of the Hispanic and the Indian—is the key to both North America’s mostly hidden past and its future. Which group of Americans will likely determine the result of the next presidential election? Who plants, fertilizes, and harvests the crops that feed this country? Who cleans American homes? Who, indeed, builds them? Who fixes the roads? Who tends to the gardens? And who leads the way to Mass? The children of Junípero Serra, that’s who.