Paul Celan’s poetry is, by most accounts, among the great postwar European literary achievements. George Steiner appeals to it as the best, and perhaps only convincing, answer to Theodor Adorno’s claim that poetry is no longer possible after the Shoah. He’s right to do so. Celan’s work is indeed paradigmatic of what poetry ought to look like in that long shadow, and it has prompted an enormous and often reverential critical response. But his poetry is always difficult and sometimes agonizing; reading it provides no easy pleasures. It has therefore been more admired than read, especially in the anglophone world.

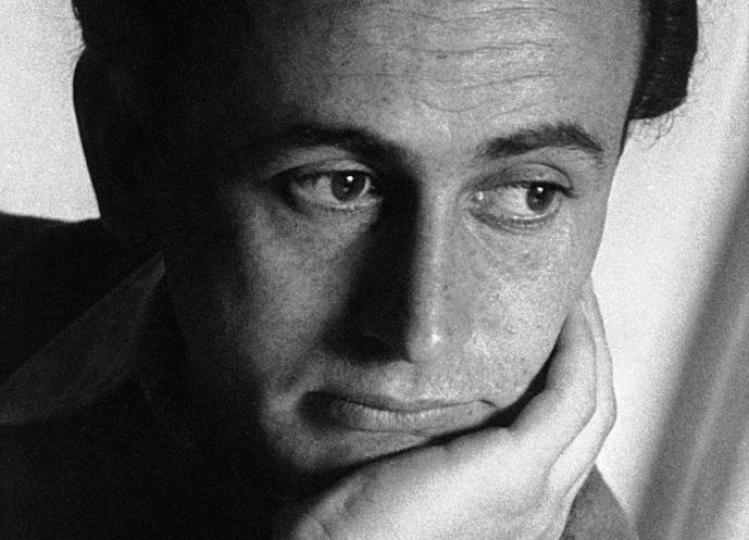

I myself came late to Paul Celan’s poetry. I was in my teens when he died in 1970 (he was forty-nine), and I remember the obituaries in the English papers and the sense that someone important had gone. I tried to read him then, but could make nothing of his condensed intensities. I was infatuated with Eliot and Yeats and Auden, and Celan was too different and too hard. I set him aside, for decades. Then, about five years ago, a friend pointed me to an audio recording, available on YouTube, of Celan reading his early poem “Todesfuge” (Deathfugue). It’s hypnotic, whether or not you can understand German. “Der Tod ist ein Meister aus Deutschland” is one of its refrains and, like most of the poem, it needs no translation. Listening to this several times prompted me to return to Celan’s poetry, hoping, now that I was older than he was when he died, that I might be able to find some way into it.

I read it, at first, in the English versions provided by Michael Hamburger, and then, more recently, in the translations of Pierre Joris. Both seem to me excellent (though in different ways), and both are usually published in facing-page German-English editions, which provide English-speakers with a window into the German. My own German is good enough for ordinary academic prose and the less colloquial newpapers, but it’s not good enough for Celan. Perhaps no one’s is. Celan’s German is about as distant from the prosaic as it’s possible to get, and while reading him in English removes some surface lexical difficulties for me, the translations make the real difficulties more evident, which is just what they should do. Those difficulties are both semantic and emotional. The words of Celan’s late poems are shattered fragments. They resist attempts to squeeze meaning out of them or to fit them together neatly, and they provoke in the reader (in this reader, anyway) a combination of admiration, frustration, and despair, together with the occasional epiphany.

That may not sound like much of a recommendation, but it is. I’ve kept returning to Celan these past five years, and, although he’s certainly no Catholic poet, I’ve found that reading him has nurtured, deepened, and partly reformed my Catholic faith.

CELAN WAS BORN in 1920 in Cernăuți in Bukovina, which was then just about to become part of Romania. It is now called Chernivitsi, and is, for the moment at least, in Ukraine. He grew up Jewish and was multi-lingual, able to speak German, Romanian, Ukrainian, Yiddish, Hebrew, French, and Russian. After experiencing, as a young man, the bloodfields of Eastern Europe and the Nazi attempt to eradicate Europe’s Jews (both his parents were killed by the SS, and he was put to forced labor), he finally left Romania in 1945 and lived in Paris from 1948 until his death. He committed suicide there by drowning himself in the Seine in April 1970.

Celan wrote some early poems in Romanian, but from 1947 on he wrote poetry only in German. He began to become known as a poet in 1952, with the publication of the volume Mohn und Gedächtnis (Poppy and Memory). This contained “Todesfuge,” which was widely read, celebrated, and anthologized in the 1950s and ’60s. The early poetry, from the late 1940s through the early ’60s, is incantatory and sometimes surrealistic, its tropes piled one on top of another. It seems designed to overwhelm the reader.

Consider, for example, the opening of “Assisi” (1955), as translated by Hamburger: “Umbrian night. / Umbrian night with the silver of churchbell and olive leaf. / Umbrian night with the stone that you carried here. / Umbrian night with the stone.” The poem ends with an explicit invocation of St. Francis, whose life has shed “brightness that will not comfort,” even though comfort is exactly what the dead beg for from Francis. There’s not much comfort in Celan’s work, and “Assisi” is a poem about death, despite its affecting evocation of the life of a place. Here death and absence frame and explain life and presence: Assisi’s shrines and olive trees and churches are given their meaning by the absence of the man they celebrate. “Assisi” has to be read several times before it achieves its effect—which is to lull readers with its incantation, so that they are, like it or not, placed in the comfortless and moon-shadowed Umbrian night. The Celan of “Assisi,” and of many of the other early poems, is a lyrical litanist.

The later poetry is very different. Between 1967 and 1976, almost six years after his death, five brief volumes appeared under Celan’s name, beginning with Atemwende (Breathturn) and ending with Zeitgehöft (Timestead). There is, in addition, a brief cycle of eleven poems collected by Celan in 1968 for publication in an anthology of work by several different poets called Aus aufgegebenen Werken (From Abandoned Works). Celan gave this cycle the lovely (and difficult) title Eingedunkelt, which Joris renders Tenebrae’d. All this has now been translated by Joris in Breathturn to Timestead: The Collected Later Poetry, published last year in a beautiful bilingual edition by Farrar, Straus & Giroux. This is the book to read if you’re new to Celan, though it should be supplemented by Michael Hamburger’s Poems of Paul Celan (2002), which contains selections from the earlier poetry as well.

The late poems are short and mostly untitled. They often appear as parts of a cycle, each part typically between twenty and a hundred words long, and each cycle including about a dozen parts. Themes and tropes run through the cycles, so that readers can build up a sense of continuity—of resonances and echoes and currents of thought. But there’s also plenty of discontinuity: scenes shift frequently, and no explicit connection links one scene to the next. The overall effect is of looking at a series of half-completed sketches of a devastated landscape, each drawn from a different point of view.

An example. In April 1968 Celan visited London briefly, staying with his aunt on Mapesbury Road. He wrote a poem there on the fourteenth of the month, which that year was both Easter Sunday and the second day of Passover. The poem begins by sketching a scene: a black woman walks down a quiet street; there’s a magnolia tree blooming and a sense of disquiet: “By her side / the / magnolia-houred half-watch / of a red, / that also searches for meaning elsewhere— / or maybe nowhere.” Meaning is perhaps available, perhaps not, but it doesn’t yield itself: it has to be sought, “elsewhere.” The obscure reference to time—“magnolia-houred half-watch”—is picked up in the next lines:

The full

timehalo around

a lodged bullet, next to it, brainish.

“Timehalo” is Joris’s translation of Zeithof—a word about as uncommon in German as “timehalo” is in English. Celan may have borrowed it from the philosopher Edmund Husserl, for whom the word identified the copresence of the past and the future in a moment of memory. Suppose you’re remembering hearing a piece of music: in the musical tone present in each memory-moment there’s a “halo,” or nimbus, provided by the tone that preceded it and the one that follows. The woman, the street, the magnolia, the silence—all are linked together in time, or by time, to a bullet in someone’s brain. Joris notes that Celan may have had in mind the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., which had happened ten days before the poem was written. Perhaps he was also thinking of the assassination attempt on the activist Rudi Dutschke in Berlin three days before. Both events involved bullets to the head. But the poem itself doesn’t say so. What it says is that violence and silence are somehow present together, proleptically and retrospectively, in a single moment of memory.

This poem is typical of Celan’s late poetry. It resists paraphrase just as it resists understanding, and for the same reason: it shows you something that can barely be seen. The words of the poem bring past and future into the present and lodge the reader, addressed as “you,” in the middle of that temporal knot. It’s not a comfortable place to be. That the poem was composed on Easter and during Passover adds to the “timehalo.” Those are days when violence, blood, and death are temporally knotted with life—the lodged bullet, brainish, with the blooming magnolia.

“Mapesbury Road” isn’t without its difficulties, but it’s almost transparent compared to some of Celan’s shorter lyrics. Here’s an untitled piece, composed in January 1968 and published as part of the sequence that begins the volume Schneepart/Snow Part (1971). It contains twenty-two words in German, and twenty-six in Joris’s translation:

Unreadability of this

world. Everything doubles.

The strong clocks

agree with the fissure-hour,

hoarsely.

You, wedged into your deepest,

climb out of yourself

forever.

“This world” is illegible: it resists our efforts to construe it. “Everything doubles” (Alles doppelt). A better translation might be “Everything repeats,” which would anticipate the shift to time language in the second verse. This doubling, or repeating, may be an element in the world’s unreadability. Whatever you, the reader, look at won’t be singular; it will already have happened and will happen again. The second verse has an air of violence. The “strong clocks,” those unavoidable time measurers, agree with, or justify, or yield the right to (all possible readings of “geben...recht”) the “fissure-hour,” the time at which a crevasse opens up. But opens between what and what? And into what? We’re not told. The “fissure-hour” (Spaltstunde), a moment of division, is part of the doubling announced in the first verse. The strong clocks announce it again, unpleasantly: their voice is hoarse.

A poem about the world’s unreadability should not be easy to read, and this one isn’t. The poem thematizes its own difficulty, as much of Celan’s late poetry does. If you read it together with the other eleven short pieces that make up the first section of Schneepart, and if you read all twelve pieces several times, Celan’s preferred images and contorted syntax begin to feel familiar. You still cannot easily say what the poems mean; after all, they are by their own account illegible. But their very difficulty begins to change the way you read not only them but also the world they describe. Once acknowledged, illegibility becomes an interpretive lens, through which absence and lack declare themselves. That, for this reader, is one of the principal results of reading Celan.

I’M A CATHOLIC reader. Not only that, but a Catholic theologian, someone whose profession and vocation it is to read, teach, and write Catholic theology. Celan was none of these things. He was a poet who was also a Jew (“Jewish poet” isn’t quite right), whose vision of the world’s resistance to meaning and its blood-bathed disorder was unusually intense, and who was himself damaged by the disorders about which he wrote.

What am I doing, then, when I read him? I don’t baptize him, or read him as if he were a Catholic manqué. Those are indefensible, indeed revolting, ways of reading Celan. But as a Catholic reader, I feel the need of a Catholic poetics, a Catholic understanding of what it is to read poetry—and not just poetry, but also other kinds of literature—made by those external to Catholicism and therefore without Catholic doctrinal and liturgical formation. I don’t read Celan, or at least not the late poetry, for beauty—the well-wrought urn, the verbal icon that participates in the world’s ordered beauty. There’s none of that in his late work. There’s intensity, flashes of light and loveliness; but the deep tones humming through it all are those of incomprehensibility and damage. The word stutters, as Celan puts it in another of his poems, and that stuttering places the fabric of speech under so much strain that almost nothing can be said, and what is said can’t be understood.

What I see when I read Celan is a series of verbal icons of the devastation in which we live. The world, for Catholics, has been devastated by the Fall. It’s full of fissures opening into incomprehensible violence and apparently random death. That’s not all it is, but it is at least that. Representation of this is a difficult trick because the nature of devastation is to resist representation. The poet must somehow find words to participate in lack and absence, and that’s exactly what Celan’s poetry does. Its difficulty is a proper part of its response to what can’t be seen.

We Catholics too often move quickly in our literature and our art toward representations of beauty, and refuse to look seriously at devastation. For some, it seems, art cannot be properly Catholic unless it is beautiful and attends to beauty. That can’t be right, and it may be worth noting that it’s mostly non-Catholics, and especially Jews, who know that it’s not right and show something else, something from which we Catholics would rather avert our gaze. When Catholic poets and painters do attempt something like what Celan does—Goya’s black paintings, for example, or O’Connor’s grotesqueries—we’re likely to exclude such work from the Catholic canon. We shouldn’t. A fully Catholic poetics would seek models for the artist’s response to the devastation. Celan is essential for this. When I read him I am deepened in my appreciation of, and given real instruction in, a doctrinal position I already hold, which is that the world is damaged, and myself along with it. When I read him I am shown something of the extent and depth of that damage, and can more easily find words to indicate what cannot be shown. Those are great gifts.