Emmanuel gets up most mornings at four o’clock to make the two-hour trip by bus and subway to the Central de Abastos, Mexico City’s huge produce market. “When I arrive at the central, I ask at different places if there is work,” he told me. “I look and I look.” If he’s hired, he’ll spend the day unloading trucks or preparing produce. If he isn’t hired, then he heads home. I asked if it was possible for someone just to tell him on the phone if there was work. “No,” he said. “I must go and ask.”

On the days when there is work, Emmanuel—who had been studying in Haiti to be an attorney—puts in between ten and twelve hours, earning two hundred pesos (twelve dollars). “I must work,” he said. “I have to support four people here and five more back in Haiti.” At the end of his workday, he gets home at nine or ten at night.

“Home” for Emmanuel, his wife Daphnee, their two-year-old son Rood, and Daphnee’s mother is a tiny one-room shack in a migrant encampment in Mexico City’s Misterios neighborhood. The shack was built with plywood and tarps and is barely big enough for the two mattresses it holds. Most of the shacks are just a few feet from an active railroad track; trains pass by a couple of times a day.

Most of the people in this encampment left their home country because there was little work—and whatever work there was paid poorly—or because of violence, often involving gangs. Many of them had walked through the Darién Gap, a dangerous, sixty-mile stretch of jungle that borders Colombia and Panama. Like almost everyone in the encampment, Emmanuel plans to ask for asylum for his family in the United States.

To enter the United States legally, migrants have to be in the northern or central part of Mexico. There, they must fill out an online CBP One (Customs and Border Protection One) application and request an appointment. If their request is accepted, they must report to one of eight intake centers in northern Mexico twenty-one days after they are notified. No one knows how long it will take to get an appointment. Everyone I spoke with in the encampment had been waiting for at least two months; Emmanuel’s family has been waiting for seven. “It is luck,” he said with a shrug. “Some people have been waiting eight, nine months.”

Most of the people in the encampment had been staying at or near CAFEMIN, a shelter a few blocks away that usually houses around a hundred women and children. Men aren’t allowed to sleep inside. Beginning in August 2023, the number of migrants at CAFEMIN swelled to almost four hundred. “When we arrived [in Mexico], my family stayed inside in CAFEMIN and I stayed outside,” said Jesús. “This was for two months.”

Although some neighbors complained about the men sleeping in front of the shelter, they were mostly tolerated. But when CAFEMIN closed in late August 2023 after a bedbug infestation, the families set up tents in front of the shelter. That’s when the complaints from nearby local residents grew louder. “Neighbors were saying there was trash and noise,” said Leonila Romero González, who works for Cáritas Mexicana’s Dimensión Pastoral del Trabajo, a migrant-advocacy organization. Jesús, his wife, and two children, along with hundreds of other families, were forced to relocate. “There was no place else for them to go,” González explained. So people built shacks next to the railroad tracks in September and October of last year. González estimates that more than a thousand people, mostly from Venezuela and Haiti, now live by the tracks.

In the morning, the encampment hums with activity. Clothes and dishes are washed, kids eat breakfast, brush their teeth, bathe. Adults congregate for a cup of instant coffee. But it’s all done outside, on railbed gravel that digs into one’s shoes.

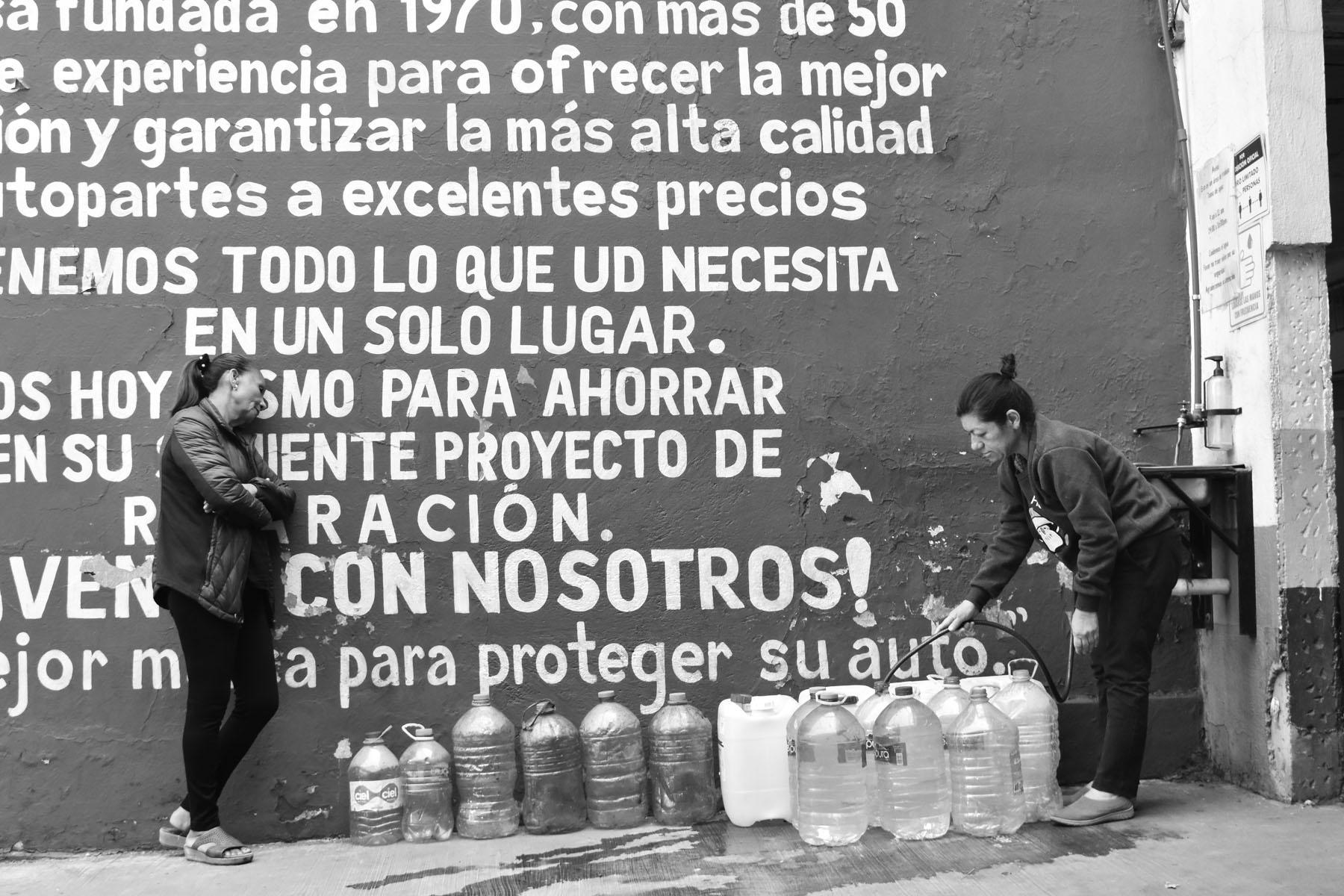

There’s no water available at the encampment itself. At Centro de Suspension, a nearby auto repair shop, people can get free water from 9:00 to 11:00 a.m. and from 3:00 to 4:00 p.m. Daniel Flores García, the manager there, told me the shop has been providing migrants with water for about a year. “The boss is a good person,” he said. “He wants to help people. Some neighbors do not want him to do this, but he continues.” People show up with as many as twenty large plastic containers, called garrafones. “We go for water every two days,” said Monica, an English teacher from Venezuela. “It is for twelve people. We arrive at 7:30. Some people show up at 5:30.” She and some friends waited for three hours one day, and were able to get only a little water before the tap was turned off. There’s also a local resident named Alejandro who provides water. When I asked why he did this when so many of his neighbors were opposed to having the encampment there, he answered: “We are all equal. There is no difference. They needed water so we let them have some.” If this free water weren’t available, the migrants would have to buy it. “Ten liters costs five pesos [twenty-seven cents],” said Monica. “Twenty liters costs ten pesos [fifty-four cents]. It would probably cost at least seventy-five pesos [four dollars] to get what we need for two days but we do not have the money.”

Once the garrafones have been filled, people carry them back to where they’re living. This can be a distance of several blocks, and a twenty-liter garrafone weighs forty-four pounds. “We use [water] to wash clothes, cook, and bathe,” Emmanuel said. There’s at least one place where migrants can bathe indoors, but it costs ten pesos a person. When families don’t have the money for that, the adults bathe inside their shacks and the kids outside.

Some local residents complained to me that migrants urinate and defecate in the street. I didn’t see any evidence of that, but it wouldn’t have surprised me. There are no toilets in the encampment, so the only options are places—usually small restaurants or homes—that charge people to use their bathrooms. “They cost five pesos, and there are twelve of us, so that is sixty pesos,” said Monica. “And they close at 10:00 at night. When we have to go [at night] we sometimes go in a bag and then put it in the trash.”

It’s not legal for undocumented migrants to work in Mexico. Those who do work in the “informal economy” are often exploited. Jesús worked in an ice-making plant earning 330 pesos (twenty dollars) for a ten-hour workday. That’s more than Mexico’s minimum wage, which is just 207 to 250 pesos (twelve to fifteen dollars) a day. But Jesús told me, “It is not fair. Mexicans [doing the same work] earned 450 to 500 pesos a day.” Jesús says his pay “is not enough to maintain a family.” Alberto, Monica’s husband, often finds work in print shops. One week, she told me, “He worked for four days, ten to twelve hours a day. They said they would pay him 2,000 pesos [$118] but they paid him only 1,500 pesos [$88].” But that wasn’t their worst experience. “One time, he worked and he did not get paid.”

At one end of the encampment is a traffic light where a few kids and a couple of adults gather every day, waiting for the light to turn red. When it does, the kids walk from car to car selling candy for a peso or two, and the adults offer to wash windshields for whatever people want to give. Nine-year-old Andismar is one of the kids selling candy. “She earns about one hundred pesos [six dollars] a day,” her father, Alexi, told me. “She wants to buy a phone.” Not to answer or make calls—she’s deaf—but to play games on it. Junior, a twenty-year-old Honduran, washes windshields. He left Honduras when a gang tried to force him to join. “If I didn’t join, they would kill me,” he told me. He had been living in the encampment for two months when I spoke with him. He usually worked for ten hours a day, earning about one hundred pesos. He was able to survive on that pittance because he’s single. Very few drivers buy the candy or agree to have their windshields washed. Most drivers will just wave the migrants away, but I observed a few who were quite nasty to them. The migrants didn’t respond to the insults; they just moved on to the next car or truck. When the light turned green, they gathered together, rested, and waited for the next red light.

Most of the money people earned went toward food. Monica told me that she ate well but added, “Sometimes we eat three meals a day, sometimes two and sometimes only one because we do not have the money.” When funds are scarce, people pool their money and buy food to share.

It is hard to overstate how poor the living conditions at the trackside encampment are. The shacks are all tiny. They have no windows, and when the tarp or plywood door is closed, the heat inside is stifling. In early May, temperatures in Mexico City were hovering around 90 degrees Fahrenheit. “It is hard because we are not accustomed to this,” said Yargalis. Back in Venezuela, she and her husband Jesús both worked and had an apartment. “We are accustomed to having privacy, a bathroom, a place to eat. For all the migrants here, it is a very difficult situation but we have to do it.”

Hostility from local residents sometimes boils over. “About three weeks ago, there was a fight between some young men in the camp and some Mexicans,” said Monica. “The Mexicans said they were going to come back and burn the camp. I could not sleep because I was afraid they would burn down the camp.” Two neighbors, Francisco Samuel Rosas Flores and his wife Leticia Melendez, saw me photographing the encampment and wanted to talk to me about it. “We as a community have nothing against migrants,” said Flores. “We worry about how they are living—it is very bad. We are trying to get the authorities to take them to a shelter with the intention that the children can eat well, that the migrants work.” (The migrant advocate Leonila Romero González reminded me that there are only four shelters in Mexico City, and all of them are packed beyond their normal capacity.) Flores told me that the migrants don’t want to work—“not in Mexico, not in the United States.” González doesn’t agree. “What migrants want is work and money to continue their journey.” She added that 90 percent of migrants want to go to the United States. None of the migrants I spoke with at the encampment planned to stay in Mexico. “I do not want to stay in Mexico because the economy is about the same as in Venezuela,” said Jesús. “We want to go to DC. My wife has a cousin there and he said there is work.”

¿Vale la pena? (“Is it worth it?”) is a phrase that’s often heard in Mexico. I asked several people in the encampment if it was worth it to have to live as they do, waiting months for an asylum appointment. Most said that it was. “This is what we have to do to go to the United States,” said Emmanuel. Marian was more emphatic. “It is worth it,” she said. “It is better here in this camp than in Venezuela. One can get work here.” But not everyone was so sure. Alexi had been living in the encampment with his wife, Digna, and their three daughters for at least a couple of months. “I cannot really tell,” he admitted. They completed the CBP One application over a month ago. He had worked in construction for a month, earning 2,500 pesos ($150) a week. “I cannot work right now because someone has to watch the children,” he explained. His wife and oldest daughter work in restaurants, earning about five hundred pesos a day (thirty dollars) between them. “It is possible to survive on this,” he said. “We want to go to Texas. I will work at anything. We do not have the American Dream. We just want to work and work.”