Most pictures of Joan of Arc depict her in the midst of glorious battle or martyrdom, but here we witness the moment that set it all in motion, the very instant she heard the voices: you can see it in the flashing eyes, flushed cheek, clenched jaw, and outstretched arm. She looks outward at something beyond the frame, possessed by a vision as immense as her eyes are wide. Her loom is behind her and her chair overturned. She has abandoned her work—in haste, we presume?—to tremble in the painting’s foreground. She appears electrified, but there is also, in her concave spine and limp left arm, a profound sort of yielding.

I speak of a portrait of Joan of Arc completed in 1879 by Jules Bastien-Lepage and now an unforgettable fixture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. It stands around eight feet tall and nine feet wide in the Met’s hall of European paintings; in this crowded corridor one encounters a more or less life-size Joan. Its hues are more potent, and Joan’s eyes more frighteningly alive, than any reproduction or description could hope to capture. When the painting was first exhibited at the 1880 Paris Salon, critics found its inclusion of the natural world and floating saints’ faces in its background rather distracting. Why is Joan swamped by earth tones, her figure positioned off-center? Why the almost kitschy iconography? In theory, a peasant girl on the edge of divine inspiration was a good subject for a painting, but Bastien-Lepage’s execution seemed sloppy. Yet it’s striking that a painting so earthy and almost photorealistic should evoke the experience of sacred vision so vividly. In summoning up Joan’s embodied charisma, Bastien-Lepage undoubtedly triumphs. On this his critics and anyone who comes within a hundred feet of the painting would agree.

Jeanne d’Arc was born in 1412 and burned at the stake around age nineteen. She was not quite a woman but in point of fact a girl, as young as twelve or thirteen, when she first heard saints’ voices calling to her in the garden. These are the three saints featured in the portrait’s frame: St. Michael in armor, St. Margaret, and St. Catherine. Joan eventually talked her way into a meeting with the Dauphin Charles VII, during which she informed him that she’d been sent to fight on behalf of France. For this tête-à-tête she donned male garb, a habit she would maintain to the end of her life. She spoke to Charles with clarity and assurance, and he was swayed: in April 1429, he dispatched the banner-waving seventeen-year-old to the besieged Orléans.

Joan’s presence was said to have roused the exhausted French battalions who, nine days after her arrival, succeeded in defeating the English. She then took on a more active role: strategizing on behalf of the French, doling out military advice to the Duke of Alençon through the Loire Campaign, pushing for her desired policy objectives, and throwing herself into battle on more than one occasion. After seeing the French through a string of victories, Joan presided over Charles’s coronation as king. Rumors spread about a virgin girl coming to France’s rescue.

A portrait of an intensely lively personality emerges from the trial transcripts. Joan impressed everyone by her self-command and by the precision with which she wielded words. Asked whether she was in God’s grace, a cunning question meant to ensnare her—if she said “yes,” she’d be committing heresy; if she said “no,” she’d be admitting guilt—she answered that if she wasn’t yet in God’s grace then she hoped she one day would be, and if she was already in God’s grace then she hoped she would stay that way. Joan’s authority rested entirely on what she continually called the “voices,” in whom she placed total trust. When asked, “In what language do your voices speak to you?” she replied, “Better language than yours.” Even now her energy leaps off the page: one glimpses how her courage and nerve might have rallied people, might have jolted them like a shot of caffeine.

Anne Carson writes of how Joan’s judges “wanted her to name, embody and describe [the voices] in ways they could understand, with recognizable religious imagery and emotions, in a conventional narrative that would be susceptible to conventional disproof.” Joan rejected this procedure with every fiber of her being, continues Carson, for “the storytelling effort was clearly hateful to her and she threw white paint on it wherever she could, giving them responses like: You asked that before. Go look at the record.... Pass on to the next question, spare me.... I knew that well enough once but I forget.... That does not touch your process.... Ask me next Saturday.”

The case hinged on Joan’s repeated refusal to reject the voices or properly contextualize them. She was, in the end, charged with “relapse” into heresy—that is, in a moment of weakness, she’d desperately agreed to discredit the voices, then promptly backpedaled. There was also the matter of her cross-dressing. Marina Warner put it a little bluntly but not unfairly: “Joan of Arc was burned at the stake by the inquisition of the Catholic Church because she refused to stop dressing as a man.” Indeed, Joan’s abjuration had specified that she must give up male dress. She was entirely secure in her divinely mandated dress code, however, and would not budge. She held that God required her to wear masculine attire—after all, it entirely suited her vocation as warrior—and that male dress helped protect her from male guards. The Joan of Bastien-Lepage’s painting is soft and feminine, but we know that in fact she was not so. “For nothing in the world will I swear not to arm myself and put on a man’s dress,” she announced.

When, long after Joan’s execution, the verdict was finally overturned, the matter of her cross-dressing was taken up directly. At the trial, witnesses had again and again testified to the appropriateness of her clothing—in particular, to her habit of attaching aiguillettes (or cords) to closely fitted pants. Guillaume Manchon noted that she “fear[ed] lest in the night her guards would inflict some act of outrage upon her,” that her clothes were practical mechanisms of self-defense in the face of lechery. Why had such witness testimony been sidelined? Other aspects of the trial were found increasingly suspect. Falsified documents came to light, and accusations mounted: Joan hadn’t been adequately informed of her charges; she had been provided insufficient legal counsel or none at all. Some said she’d been blameless—that the Burgundians had been out to get her and had played dirty. Indeed, most of the clergy at her trial had backed the English and sought to undermine Charles’s authority (this in order to buttress their own claims to France). Undermining Joan—who, recall, had overseen Charles’s coronation—was an expedient way to undermine Charles himself. Viewed under this aspect, Joan’s guilt had been a foregone conclusion. Pope Pius II would overturn her verdict in 1456, but it wasn’t until centuries later, in 1920, that Joan would be canonized by the Roman Catholic Church. She was subsequently declared sainte patronne of France, having run the gamut of official spiritual rankings: from unrepentant heretic to saint.

Joan gripped the artistic imagination for centuries to follow. Schiller fashioned a Romantic vision of her in his 1801 play, the basis of Verdi and Tchaikovsky’s later operas. Most notable was the nineteenth-century French cult from which Bastien-Lepage emerged. The German Empire had annexed territory in Lorraine, St. Joan’s birthplace, after France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian War; her image then became a powerful symbol for those who wanted to reclaim the territory. Contrast Bastien-Lepage’s interpretation with others from the same era—for example, Emmanuel Frémiet’s bronze statue, completed in 1874 and displayed in the Place des Pyramides in Paris. There, a manly Joan, straddling a horse, is attired in the accoutrements of a knight. Peter Paul Rubens and Ingres had also painted Joan in uniform, while Rosetti would picture her with sword in hand. But in Bastien-Lepage’s rendering we find no armor, no sword, no metallic glint of any kind. Her garments are romantically rumpled, her skin is translucent. She is distinctly feminine and overlayed with the sensual gleam of the Pre-Raphaelites.

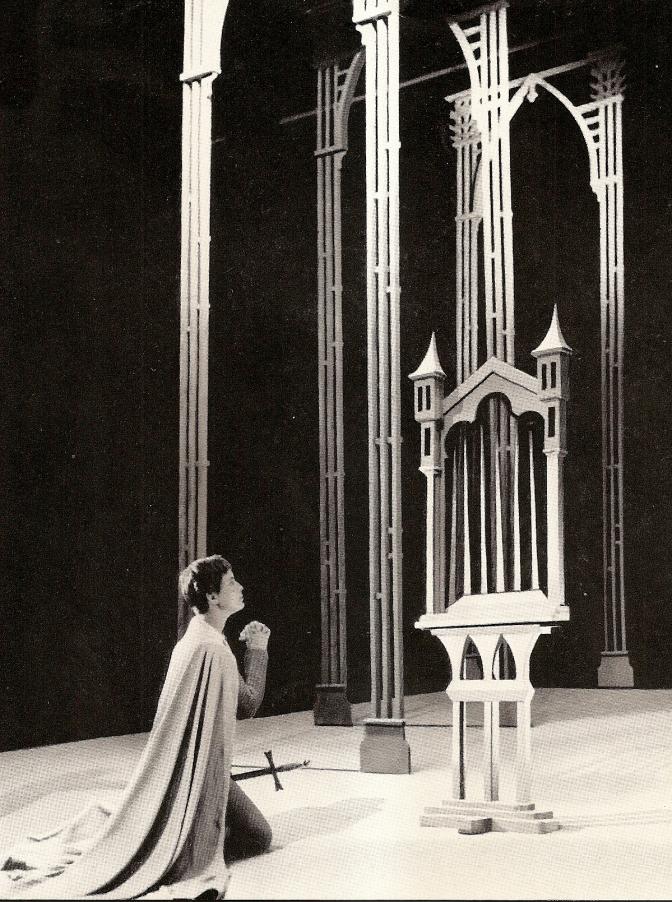

Another curious phenomenon emerged in the nineteenth century: Joan’s tendency to fascinate hardened atheists and those otherwise hostile to religion. Mark Twain devoted a book to her, a novelization of Joan’s life called Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc that took him the better part of fourteen years to complete and was his personal favorite of his own works. Twain deemed Joan “by far the most extraordinary person the human race has ever produced.” Bertolt Brecht produced a proletarian drama called Saint Joan of the Stockyards. But it was George Bernard Shaw’s 1923 play Saint Joan—a century old this year—that would achieve a sort of masterpiece status. These playwrights construct Joans after their own hearts: Brecht’s Joan is anti-capitalist and Shaw’s is proto-feminist (and proto-Protestant, but that’s another story).

Shaw wished to rescue Joan from her reputation as dreamy gamine—to dispense with the sighs and rosy cheeks and restore to her some severity and steel. Joan’s ideal biographer, he argues in his celebrated introduction, “must be capable of throwing off sex partialities and their romance, and [of] regarding woman as the female of the human species, and not as a different kind of animal with specific charms and specific imbecilities.” It’s a task he undertakes in defiance of the stock nineteenth-century attitude toward Joan, a sort of condescension he sums up as follows: Joan’s visions “were delusions, but...she was a pretty girl, and had been abominably ill-treated and finally done to death by a superstitious rabble of medieval priests.” Shaw takes shots at everyone. His verdict on The Maid of Orleans: “Schiller’s Joan has not a single point of contact with the real Joan, nor indeed with any mortal woman that ever walked this earth.” Andrew Lang and Mark Twain are “equally determined to make Joan a beautiful and most ladylike Victorian.”

What was the actual and substantive animus against Joan, the real reason she had been burned at the stake? Shaw’s diagnosis has a kind of brazen simplicity: “Essentially for what we call unwomanly and insufferable presumption.” He diligently studied the trial transcripts in an effort to recreate Joan’s human texture, zeroing in on her tendency to lecture and talk down to people, often to male statesmen twice her age. She was utterly helpless at the feminine art of smoothing things over. Joan was quick, harsh, and beguilingly self-assured. She had no spite or worldly cunning, but she refused to massage the egos of those around her or to conceal her overwhelming belief in the rightness of her vision. In this she did herself no favors: “If she had been old enough to know the effect she was producing on the men whom she humiliated by being right when they were wrong, and had learned to flatter and manage them, she might have lived as long as Queen Elizabeth,” observes Shaw. He dramatizes his interpretation to humorous effect:

CHARLES: Yes: she thinks she knows better than everyone else.

JOAN [distressed, but naïvely incapable of seeing the effect she is producing]: But I do know better than any of you seem to. And I am not proud: I never speak unless I know I am right.

Shaw goes on to present Joan in Nietzschean terms as a “superior being,” a great individual, indeed a genius: “A genius is a person who, seeing farther and probing deeper than other people, has a different set of ethical valuations from theirs, and has energy enough to give effort to this extra vision and its valuations in whatever manner best suits his or her talents.” Shaw sees something genuinely frightening in the seeming amorality of such visionaries:

Fear will drive men to any extreme; and the fear inspired by a superior being is a mystery which cannot be reasoned away. Being immeasurable it is unbearable when there is no presumption or guarantee of its benevolence and moral responsibility: in other words, when it has no official status.

Female genius, to be sure, had no “official status.” Like Simone Weil after her, Joan probably had a tendency to unsettle and deeply irritate those who were not altogether entranced or convinced. It’s true: there is something a touch inhuman and even infuriating about such strength of mind, such stubborn singularity of purpose, especially in an illiterate and apparently guileless teenage girl. Like Oscar Wilde, Shaw’s contemporary and sometime-friend, Shaw was interested in the genius or charismatic individual as a historical force. Joan embodied for him the “unaveraged individual representing life possibly at its highest actual human evolution and possibly at its lowest, but never at its merely mathematical average.” Such “unaveraged” and irrepressible life force must either be snuffed out through a verdict (heretic or witch, as the case may be) or kept in check by being elevated beyond reach (saint). For such devastating force of personality to go on burning unmeasurably and with no “official status” would be intolerable—would “drive men to any extreme.”

Shaw continually insists that Joan was not beautiful. “She was not a melodramatic heroine: that is, a physically beautiful lovelorn parasite on an equally beautiful hero, but a genius and a saint, about as completely the opposite of a melodramatic heroine as it is possible for a human being to be.” He elaborates with gusto:

Not one of Joan’s comrades, in village, court, or camp, even when they were straining themselves to please the king by praising her, ever claimed that she was pretty. All the men who alluded to the matter declared most emphatically that she was unattractive sexually to a degree that seemed to them miraculous, considering that she was in the bloom of youth, and neither ugly, awkward, deformed, nor unpleasant in her person…. [M]en were too much afraid of her to fall in love with her.

Shaw’s prose reaches a feverish pitch at such moments: one almost gets the impression that he regards beauty and genius as mutually exclusive, or at least that he undervalues beauty as a legitimate ingredient of genius. In any event, Shaw’s Joan has little in common with Bastien-Lepage’s. For the latter she is undoubtedly picturesque, but her flashing eyes, eyes that burn through canvas, do remind you of Shaw’s depiction: she is seeing you, is seeing beyond you, more than you’re seeing her. The idea that she’d be courting your approval is laughable. She is supremely indifferent to your regard; her sights are set altogether higher.

Praise for Saint Joan was not universal. T. S. Eliot griped that Shaw’s Joan was “perhaps the greatest sacrilege of all Joans: for instead of the saint or the strumpet of the legends to which he objects, he has turned her into a great middle-class reformer, and her place is a little higher than [British suffragette] Mrs. Pankhurst.” A prosaic and politicking Joan had not been Shaw’s intention, but that was nonetheless an overtone detected by some. (Eliot would admit that the epilogue of his own play Murder in the Cathedral may have drawn inspiration from Saint Joan.) Shaw’s friend and sparring partner G. K. Chesterton wrote that “he has a heroically large and generous heart; but not a heart in the right place.”

Through the twentieth century and beyond, Joans of every shade and stripe multiplied. A 1957 adaptation of Shaw’s play starring a pre-Breathless Jean Seberg was universally panned, causing the actress to lament that she’d been “burned at the stake by the critics”; she also suffered literal burns on set. Today we can nod along as Morrissey croons “and now I know how Joan of Arc felt.” Our world is steeped in Joan’s symbolism even as we grow further and further from the context in which her execution and canonization had immediate stakes. Every age will apply and misapply the fragments of her life to suit its needs. I do not propose to weigh in on ecclesiastical matters, though I have my instincts and allegiances, nor do I wish to consider questions of hysteria, schizophrenia, or anorexia. Joan is plainly a visionary and thus, to paraphrase Goethe, a mirror in which any subsequent age admires itself. Labels stick to enigmas and promptly fall right off.

As Joan’s body convulsed in flame, one onlooker allegedly cried: “We have burned a saint!” She was certainly not the only saint to live before his or her time had come. Such untimely people will later have their heretical insolence transposed into prophetic courage. Human vision is cloudy and ill-equipped to make such determinations without the benefit of retrospect, and even the deepest rot may look like orthodoxy if it bears the stamp of immemorial tradition. “Mortal eyes cannot distinguish the saint from the heretic,” murmurs Cauchon in Saint Joan. “Must then a Christ perish in torment in every age to save those that have no imagination?”