From the beginning we know the end; The Road to Jonestown shows its cards immediately. In the book’s prologue, officials discover more than nine hundred of Jim Jones’s followers dead in the Guyanese jungle. They are decomposed in piles, faces melting in the tropical heat. Some of the bodies have bruises, marks of resistance. The tragedy is deemed a murder-suicide. Some took their poison willingly; others, children included, had it squirted into their mouths. The year is 1978.

Jeff Guinn’s new biography-cum-history is a study of persuasion and power in Peoples Temple, the twentieth-century socialist cult led by preacher Jim Jones. Many readers, like me, come to the story aware of its associated quip: “Don’t drink the Kool-Aid.” (Morbid party fact: the poison was actually mixed with generic Flavor Aid, not the pricier Kool-Aid powder.)

But Guinn’s steady, removed prose can make us forget what we know. The book is a slow reveal of sensationalist material, methodically tracing Temple’s history. In 1954, Jones established a multi-racial, charismatic Indianapolis congregation. In 1965, he and many of his followers relocated to Redwood Valley, California, establishing a powerful megachurch with campuses in San Francisco and Los Angeles. Finally, in 1973, work began on Jonestown, a clearing in the midst of the Guyana jungle. Moving from inspiring Indianapolis sermons to wild Guyananese rants, Guinn demonstrates why so many found Jones’s message of a people set apart to be compelling, inspiring, worth moving and dying for. When tragedy strikes, we are startled; we, like his followers, didn’t think Jim would really do it.

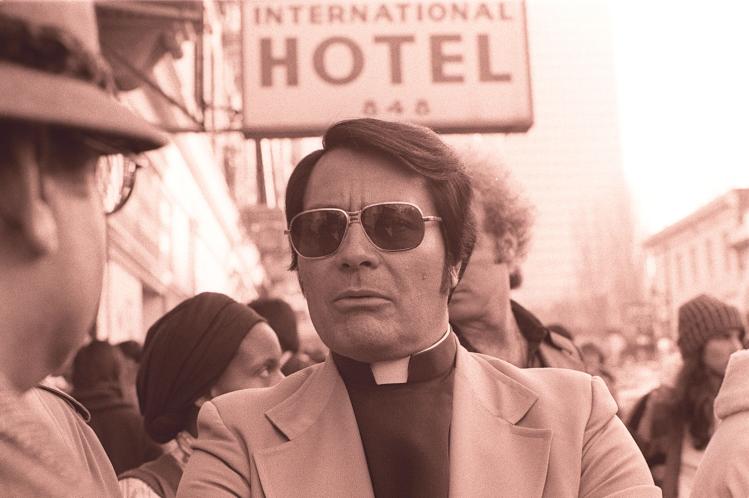

Jones possessed typical dictatorial traits. He was magnetic, preaching hour-long stints on the revival circuit, peeing behind the pulpit to keep from taking breaks. He was charming; he learned names quickly, curried favor with San Francisco politicians like George Moscone and Joseph Alioto, and gained official, legitimizing recognition from the Disciples of Christ. He was cunning. His famous healings were performed with sleight-of-hand and chicken offal disguised as tumors. His prophecies were fueled by audience spies; they gathered intimate information from guests before services, then reported the details to their leader. He smuggled money overseas in tampon boxes. Jones was cruel. He flaunted affairs with both genders in front of his wife Marceline, and openly fathered children by other women. In ceremonies called White Nights, he pretended to initiate mass suicides, noting who was willing to die for him. Jones was hypocritical. He used church coffers for his family’s lavish vacations, even as his followers donated their cars, homes, and heirlooms. He relied on drug cocktails, although his followers were held to strict sobriety. As a child, Jones admired the Nazis, goose-stepping in his Lynn, Indiana, backyard. He was paranoid. He forbade outside friendships, censored mail, feared the media, drugged dissenters, and threatened defectors. He was egomaniacal, certain that his church was the primary concern of governments everywhere, and determined to be remembered. He practiced “situational ethics.” People loved Jones because he seemed to love them; people followed him because he led convincingly.

But as Guinn makes clear, Jones was no garden-variety tyrant. “Jim Jones would frequently be compared to murderous demagogues such as Adolf Hitler and Charles Manson,” Guinn writes. “These comparisons completely misinterpret, and historically misrepresent, the initial appeal of Jim Jones to members of Peoples Temple. Jones attracted followers by appealing to their better instincts.” Although Jones did use fear—of nuclear fallout, of government interference—he also motivated followers with calls for compassion and justice. His was a cult of personality, but also a cult of action and ideas. Peoples Temple operated a system of clean, affordable nursing homes, as well as a successful drug-rehabilitation program for teens. It funded college for low-income students. Members volunteered for community cleanups; they ran soup kitchens and clothing drives. The sick and poor were cared for; jobs were found for the unemployed. Jim preached racial equality; in Indianapolis, he integrated many local restaurants by paying for black members to dine with him. He adopted multi-racial children to prove his commitment to unity. In light of Jones’s radical social mission, it’s easier to understand why thinking people stayed in the Temple—they believed they were doing good work, and they were.

What the book doesn’t do (and doesn’t because it can’t) is establish what Jones really believed. Was he a genuine socialist? Did he care about racial equality? Was he merely a power-hungry maniac, who saw the equality message as a way to manipulate and rule over others? Did he fear nuclear fallout, or simply use it as an excuse to keep moving? Was he a Christian? Jones imbued his sermons with vague Gospel language, appealing to older, orthodox followers without actually quoting Scripture. He operated within the black-church tradition, performing healings and invoking the Promised Land. But Jones also publicly ranted against an invisible “Sky God.” He increasingly defined himself as a divine, as a reincarnated spirit, even as an alien. Those closest to him, including Marceline, didn’t buy this. But did Jones?

And what did Jones’s followers think? Although the book is built on interviews with defectors, survivors, and family members, the nine hundred dead are voiceless. What of Marceline, who kept her vows but resisted the mass suicide? What of Jones’s mother, Lynetta, who always believed her son was special? What of Sharon, the mother who urged on the murder of her own children? How much of this devotion was delusion? Pretended? Genuine? Partial? “What you thought Jones said depended on who you were,” Guinn quotes. Each congregant focused on what appealed to him or her—the hodgepodge religion, the utopian politics, the man himself—and downplayed what didn’t. Overworked, exhausted, and penniless, they had no time to think. “Keep them poor and keep them tired, and they’ll never leave,” Jones said.

After finishing Jonestown, I wondered if I could understand Jones by watching him. Guinn avoids individual scenes, preferring general descriptions. I wanted to see the preacher in action. Curious, I found a video online. It shows a huge crowd of congregants dancing, clapping, singing, wailing. Jones speaks in a buttery tenor; he stands handsome in a dark suit, a crisp part in his hair. He calls people “honey” and “baby.” He heals a woman from the pulpit. “Sister Ingram, you’re concerned about the losing of your sight,” he intones. “Look at my face. I’m going to hold up some fingers. Concentrate hard. I love you. The people love you. Most importantly, Christ loves you. What do you see? How many fingers?” “Three,” whispers the woman, and the crowd explodes. She is weeping. Even knowing how Jim did it—the woman was probably a plant—the scene is still weird, wild, disturbingly moving. I watch Jones’s face. His brow is furrowed. He licks his lips, and smiles without showing his teeth. What is he thinking—most likely, probably? A whole book behind me, the question can’t be answered.

‘The Road to Jonestown’

Jim Jones and the Peoples Temple

Jeff Guinn

Simon & Schuster, $28, 468 pp.