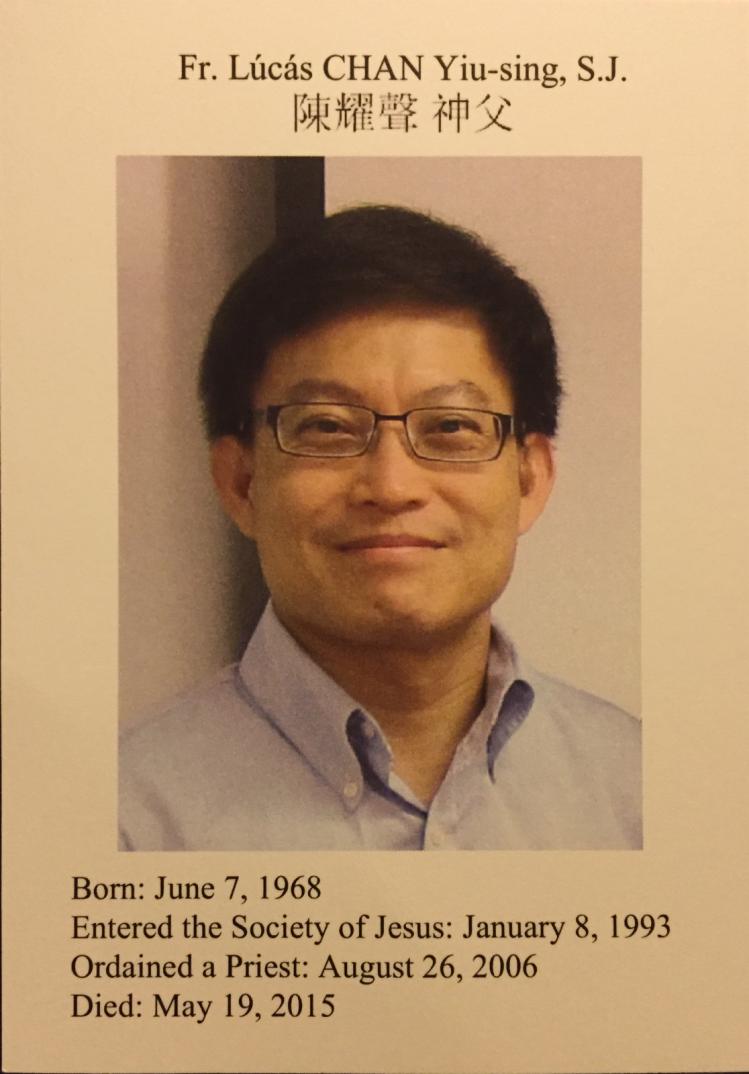

Last Sunday, I wrote “Grieving at Pentecost.” Now I would like to share with you a part of the homily I gave at Lúcás’ funeral. It’s the first section where I consider his foundational contributions to Biblical ethics. Later I spoke about ways he was a bridge-builder among friends.

In the beginning of each of his two books, Lúcás (Yiu Sing Luke) Chan, S.J. refers to building bridges. He begins his first book, The Ten Commandments and the Beatitudes: Biblical Studies and Ethics for Real Life, with “A schema for bridging biblical studies and Christian ethics” and he introduces his second book, Biblical Ethics in the Twenty-first Century: Developments, Emerging Consensus, and Future Directions, with the overarching notion of “building bridges.”

Lúcás wrote about building bridges because he was a bridge builder. The man whose spiritual and intellectual formation, began in Hong Kong and ended in Milwaukee, had built bridges as he moved to England, Singapore, Cambodia, Macau, the Philippines, the U.S., Ireland, as well as Italy and Germany.

As a moral theologian Lúcás built the bridge between biblical theology and Christian Ethics. Lúcás’ argument was clear and critical: if someone wants to do biblical ethics they need to have the competency of a biblical theologian who can tell us what the scriptural text means and the competency of a moral theologian who knows how to think through the contemporary ethical application of the meaning of the text. As Dan Harrington noted in Lúcás’ first book on the ten commandments and the beatitudes, Lúcás makes the argument, but what is more remarkable, he “performs it.” He takes each of the ten commandments and the eight beatitudes, tells us what each means and how each can be applied by a virtue. For instance, on the second beatitude, “Blessed are they who mourn, for they shall be comforted,” Lúcás shows us that the grief Jesus is addressing is not over what one person has lost, but rather whether one empathizes for another’s loss. The second beatitude follows from and is deeply connected to the first beatitude: the blessed are those mourning for those who are poor in spirit, that is, for those in the community who are struggling. Lúcás writes, “Such is the lot of the disciples of Christ- when our brothers and sisters suffer, we cannot help but mourn.” (171) Then, after describing the meaning of the text, Lúcás proffers solidarity as the contemporary virtuous application of the second beatitude. For this reason, Harrington called Lúcás’ book, “a manifesto for the double competencies of a biblically based ethics.” In America magazine, Harrington called Lúcás’s work, “a milestone.”

Lúcás not only built the bridges between Christian ethics and biblical theology, he became recognized as its bridge builder par excellence. Just this month, the editors of the forthcoming Jerome Biblical Commentary, arguably the most relevant and revered commentary in the English language, invited Lúcás to write a 26,000 word essay, “The Bible and Ethics.” It was for this reason too that David Schultenover, the editor of Theological Studies, invited Lúcás to write this year his Moral Note on “The Bible and Theological Ethics” and that Catholic Theological Ethics in the World Church commissioned him to edit an international collection entitled, the “Bible and Catholic Theological Ethics.” It is hard to think of any other theologian who dedicated himself so completely these past ten years to building the bridge between moral theology and the bible: he pioneered the field.

Lúcás built other bridges. He wrote and spoke around the world on the bridge between Christian and Confucian ethics. For instance, he concluded his first book precisely by comparing the Fourth commandment with the Confucian honoring of elders. Elsewhere, he and I wrote an essay on it for the Jesuit, Macau-based Chinese Cross Currents. On every occasion, he constructed this bridge out of the virtues and he knew how important these bridges were. For instance, at Berkley when he gave a major lecture on Christian and Confucian ethics, he concluded his power point lecture with a series of photos of bridges, the last being the Golden Gate Bridge.

He also built bridges in ethics between the Old and New Testaments, by emphasizing that the ten commandments and the eight beatitudes are the two moral pillars of our religious tradition. For this reason we chose these two readings for his funeral today in Milwaukee and for his memorial mass in Hong Kong.

He also bridged those scriptures together on concrete urgent issues by focusing, for instance, on the Gospel command to welcome the stranger, today, the immigrant, and by proposing a biblical male role model, the Old Testament figure, Boaz, who welcomed Ruth and Naomi, as a hospitable role model. That study of Boaz appeared in his first published article nearly ten years ago, entitled, “A Model of Hospitality for Our Times.” Only last month he revisited Boaz for a contribution to an essay on migration today.

Most of all he built bridges among us. In this congregation today, there are his Irish friends, his Cantonese friends, his Boston friends, his California friends and, most importantly, his new found Milwaukee friends. He has friends everywhere: consider the memorial services. While we are here today in Milwaukee at this funeral, Boston College friends celebrated their memorial mass last week, the Irish Jesuits and Trinity College had its memorial mass earlier today in Dublin, the Boston Cantonese parish has their memorial mass on June 6th, and the community in Hong Kong will celebrate their memorial with Cardinal Tong on June 8, all remembering Lúcás Chan, S.J., Bridge-Builder.