Bayard Rustin was a pacifist, a radical, black, and gay. Not exactly well positioned to influence mid-century America. Yet, from the 1940s through the ’60s, he marshaled his considerable talents—as an organizer, strategist, speaker, and writer—to challenge the economic and racial status quo. Always an outsider, he helped catalyze the civil-rights movement with courageous acts of resistance. Rustin was a key aide to Martin Luther King Jr. and the lead organizer of the 1963 March on Washington—a job he seemed to have prepared for his entire life.

A hundred years after his birth, and twenty-five years after his death, Rustin may finally be getting the recognition he deserves. A variety of civil-rights and gay-rights groups are honoring Rustin with conferences and other events. City Lights Books recently published I Must Resist: Bayard Rustin’s Life in Letters, edited by Michael G. Long. In his hometown of West Chester, Pennsylvania, the Chester County Historical Society recently launched an exhibit about Rustin.

The youngest of eight children, Rustin was raised by his grandparents. Although they attended his grandfather’s African Methodist Episcopal church, Rustin was strongly influenced by the Quaker faith of his grandmother, who was an early member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Some NAACP leaders, including W. E. B. DuBois, stayed with the Rustins when they were on speaking tours.

Rustin was a gifted student, an outstanding athlete, a skilled orator and poet, and an exceptional tenor. Early in his life he revealed a strong social conscience. In high school he was arrested for refusing to sit in the West Chester movie theater’s segregated balcony, nicknamed “Nigger Heaven.”

Rustin attended two black colleges (Wilberforce University and Cheyney State) before moving to New York City in 1937. He enrolled briefly at the City College of New York, where he got involved with the campus Young Communist League. He was attracted by their antiracist efforts—including their fight against segregation in the military—but he broke with the Communist Party after a few years.

Rustin sang in nightclubs to earn money, and once appeared with Paul Robeson in the Broadway musical John Henry, but he found other ways to channel his prodigious energy, his outrage against racism, and his growing talent as an organizer.

He found two mentors who shaped his philosophy and employed him as an organizer. One was A. Philip Randolph, a socialist who founded of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first African-American labor union. Randolph was the nation’s most militant civil-rights leader. The other mentor, A. J. Muste, was a radical minister and former union organizer. Time magazine called him the “No. 1 U.S. pacifist.” He introduced Rustin to the teachings of Gandhi. Rustin’s commitment to Gandhi’s principles, along with his Quaker beliefs (he officially joined the church in 1935), shaped his activism for the rest of his life.

Randolph hired Rustin in 1941 to lead the youth wing of the March on Washington, designed to push President Franklin Roosevelt to open up defense jobs to black workers as the United States geared up for World War II. After FDR agreed to issue an executive order forbidding racial discrimination in defense industries, Randolph called off the protest, angering Rustin and opening a temporary breach between them.

Then, under Muste’s guidance, Rustin began a series of organizing jobs with the Fellowship of Reconciliation (a Christian pacifist group), the American Friends Service Committee, and the War Resisters League. These were small, mostly white organizations that provided Rustin with a home base, a title, a newsletter, and a network of activists around the country. A charismatic speaker, Rustin kept up a hectic travel schedule, preaching the gospel of nonviolence and civil disobedience on campuses, in churches, and at meetings of fellow pacifists. Rustin viewed nonviolent resistance as a “way of life”—not just a policy. Wherever he spoke, Rustin inspired at least a handful of students to join his cause; that is how he recruited the next generation of civil-rights and antiwar activists.

As a Quaker and conscientious objector, Rustin was legally entitled to do alternative service rather than military service during World War II. But on principle, objecting to war in general and the segregation of the armed forces in particular, he refused to serve even in the Civilian Public Service. “War is wrong,” he wrote to his draft board in 1943. “Conscription for war is inconsistent with freedom of conscience, which is not merely the right to believe but to act on the degree of truth that one receives, to follow a vocation which is God-inspired and God-directed.”

In 1944 Rustin was convicted of violating the Selective Service Act and served two years in federal prisons in Kentucky and Pennsylvania. In Kentucky he protested the pervasive segregation within prisons, facing violence from prison guards and white prisoners. In Pennsylvania, prison officials kept Rustin away from other inmates so he wouldn’t influence them with his radical ideas. As Rustin wrote after his release in June 1946:

We were there by virtue of a commitment we had made to a moral position; and that gave us a psychological attitude the average prisoner did not have.... We had the feeling of being morally important, and that made us respond to prison conditions without fear, with considerable sensitivity to human rights.... It was by going to jail that we called the people’s attention to the horrors of war.

After leaving prison, Rustin rejoined the Fellowship of Reconciliation (the Christian pacifist group he’d previously worked for) and resumed his career as a peripatetic organizer. In April 1947 he led the group’s interracial Journey of Reconciliation, engaging in nonviolent acts of civil disobedience through four southern and border states. These demonstrations served as a precursor to the Freedom Rides of the early 1960s. He and others were arrested in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, and Rustin spent twenty-two days on a chain gang.

The Journey of Reconciliation was not without controversy, even among civil-rights groups. Thurgood Marshall, who led the NAACP’s legal division, warned that the “disobedience movement on the part of Negroes and their white allies, if employed in the South, would result in wholesale slaughter with no good achieved.”

In 1948 Rustin went back to work for Randolph in order to push President Harry S. Truman to enforce and expand FDR’s antidiscrimination order. They organized protests in several cities and at the 1948 Democratic National Convention. Their work paid off: Truman desegregated the military and outlawed racial discrimination in the federal civil service later that year.

In the late 1940s and early ’50s, while still working for the Fellowship of Reconciliation, Rustin visited India, Africa, and Europe, where he made contact with activists in various independence and peace movements. Increasingly, he viewed the struggle for civil rights in the United States as part of a worldwide movement against war and colonialism.

It was at this time that Rustin’s homosexuality became a public problem for him. In 1953 he was found having sex with a man in a parked car in Pasadena, California, and was arrested for “public indecency.” Although Rustin was unusually open with his friends about his homosexuality, this was the first time it had become public. Gay sex was a crime in every state. Muste fired him for jeopardizing the Fellowship of Reconciliation’s already controversial reputation. But Randolph got him a similar job with the War Resisters League, a pacifist group founded in 1923, where Rustin worked for the next twelve years.

Over the next decade, Rustin receded from public view. He continued to play a critical behind-the-scenes role as an organizer within the civil-rights movement. At Randolph’s behest, he went to Montgomery, Alabama, in 1955 to help local leaders organize a large-scale bus boycott.

During this period, Rustin began advising Martin Luther King Jr., who had no organizing experience, on the philosophy and tactics of civil disobedience. Rustin was “the perfect mentor for King at this stage in the young minister’s career,” observes John D’Emilio, author of Lost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard Rustin. Over “the ensuing months and years,” D’Emilio writes, “Rustin left a profound mark on the evolution of King’s role as national leader.”

Much of Rustin’s advice would be given from a distance, in phone calls, memos, and drafts of articles and book chapters he wrote for King. He had to cut short his first visit to Montgomery because, as a gay man and a former Communist, he was a political liability. Just at the moment when Rustin might have helped lead the mass movement for which he’d been working his entire adult life, he had to retreat to the shadows.

At the end of 1956, the Supreme Court ruled that Montgomery’s segregated bus system was unlawful. The victory could have remained a local triumph rather than a national bellwether, but Rustin, along with Ella Baker and Stanley Levinson (another King adviser), had an idea for building a “mass movement across the South” with “disciplined groups prepared to act as ‘nonviolent shock troops,’” as Rustin put it. This was the genesis of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference—conceived by Rustin and founded with King as its first president—which would catapult King to the national stage. Baker was hired to build the organization, and Rustin became King’s strategist, ghostwriter, and link to northern liberals and unions.

To many Americans, the civil-rights movement was a confusing mosaic of organizations—NAACP, SNCC, CORE, the Urban League, SCLC—all competing for attention, each with a different approach. But in 1963, Randolph, as the elder statesman of the movement, pulled together the leaders of the major civil-rights, labor, and liberal religious organizations and laid out his plan for a march on Washington. Randolph envisioned a march that would push for federal legislation, particularly for the Civil Rights Act. President John F. Kennedy had proposed that law, but it had stalled in Congress. The event would emphasize jobs as well as civil rights, which reflected Randolph’s long history as a union organizer and champion of racial justice. Its name would be the March for Jobs and Freedom. And Randolph wanted Rustin to run it.

The leaders Randolph gathered endorsed the plan. But NAACP president Roy Wilkins objected to putting Rustin in charge of the march, because of his radicalism and his homosexuality. Randolph outmaneuvered Wilkins by announcing that he would be its director and choose his own deputy: Rustin, of course.

Kennedy tried to dissuade them from holding the march, contending that it would undermine support for the Civil Rights Act. But Randolph would not be cowed. Nor would he be bullied by other civil-rights leaders who voiced objections to Rustin’s role.

Three weeks before the August 28 march, Sen. Strom Thurmond, a South Carolina segregationist, publicly attacked Rustin on the floor of the Senate by reading reports of his Pasadena arrest for homosexual behavior a decade earlier—documents he probably got from FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. Randolph bravely defended Rustin’s integrity and his role in the march, but, as biographer John D’Emilio noted, thanks to Thurmond, “Rustin had become perhaps the most visible homosexual in America.”

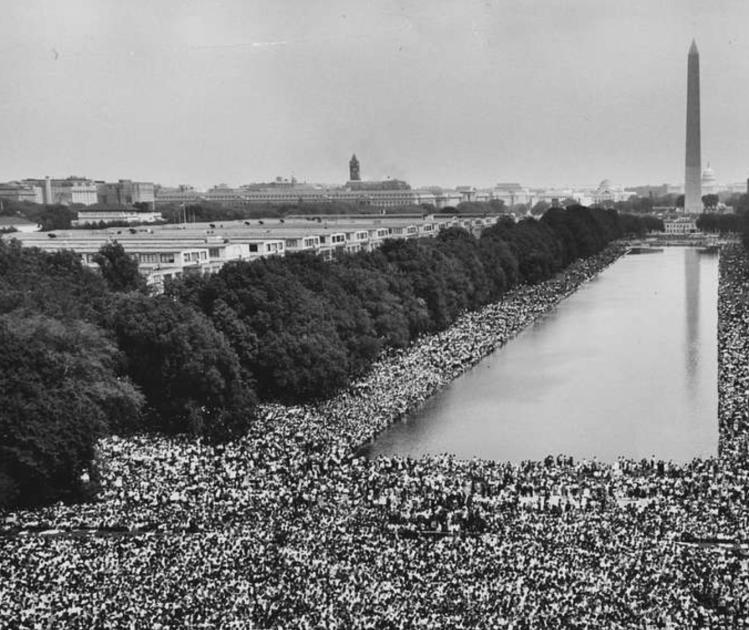

The march was a huge success. It was not only the highlight of Rustin’s career but perhaps the high point of the movement itself. More than 250,000 people attended. King delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech. Ten months later, in the aftermath of Kennedy’s assassination, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act.

The final twenty-four years of Rustin’s life was something of an anti-climax. He continued his organizing work within the civil-rights, peace, and labor movements. He was still in demand as a public speaker, and he was still valued for his strategic brilliance. But he never again had the same influence he did when organizing the Washington march. King—whose opponents were planting stories that he was under the influence of Communists—continued to rely on Rustin’s advice, but always at a safe distance, fearful the movement would be tarnished by Rustin’s liabilities.

After Congress passed the Voting Rights Act in 1965, Rustin wrote a controversial article, “From Protest to Politics,” in the then-liberal magazine Commentary. In that piece he argued that the coalition that had come together for the March on Washington needed to place less emphasis on protest and focus on electing liberal Democrats who could enact a progressive policy agenda centered on employment, housing, and civil rights. Rustin drafted a “Freedom Budget,” released in 1967, that advocated “redistribution of wealth.” His ideas influenced King, who increasingly began to talk about the importance of jobs and wealth redistribution.

Rustin’s ideas, however, were controversial among the young Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) radicals. They did not trust the unions or the Democratic Party. The group had become a major advocate of “black power,” an idea Rustin opposed because it undermined his commitment to coalition politics and racial integration.

But the two biggest obstacles to Rustin’s program were the war in Vietnam, which drained resources and attention away from LBJ’s Great Society and War on Poverty, and the urban riots that began in 1965 in Los Angeles and triggered a backlash against the civil-rights movement. Rustin was among the first public figures to call for the withdrawal of all American forces from South Vietnam, but as LBJ escalated the war, Rustin muted his criticisms. He wanted to avoid alienating LBJ, key Democrats, and union leaders who supported the war—and who funded the A. Philip Randolph Institute, which had been created in 1964 to provide Rustin with an organizational home. When King announced his opposition to the war in 1967, it caused a rift between the two men. As a result, Rustin—who had for decades been one of the nation’s most important pacifists—was absent from the antiwar movement, which cost him credibility among New Left student activists.

Ironically, Rustin’s homosexuality became a centerpiece of his final few years. He had been wary of the burgeoning gay-rights movement, which exploded after the Stonewall riot in New York City in 1969. But at the end of his life, when he was involved in a stable relationship, he began speaking publicly about the importance of civil rights for gays and lesbians. Thanks in part to a 2002 documentary, Brother Outsider, Rustin has become an icon for gay-rights activists.

In 1986, a year before he died of a burst appendix, Rustin was asked by Joseph Beam, a writer and gay-rights activist, to contribute an essay to a volume on the experience of gay black men. Rustin declined. But his reply to Beam provides an eloquent summary of the foundation of his life’s work.

My activism did not spring from my being gay, or, for that matter, from my being black. Rather, it is rooted fundamentally in my Quaker upbringing and the values that were instilled in me by my grandparents who reared me. Those values are based on the concept of a single human family and the belief that all members of that family are equal.... The racial injustice that was present in this country during my youth was a challenge to my belief in the oneness of the human family. It demanded my involvement in the struggle to achieve interracial democracy, but it is very likely that I would have been involved had I been a white person with the same philosophy. Needless to say, I worked side-by-side with many white people who held these same values, some of whom gave as much, if not more, to the struggle than myself.