For the most part the boy’s recreations were limited to those things which were free: walks in the mountains, a swim in the Danube, a free band concert. He read extensively and was particularly fascinated by stories about American Indians. He devoured the books of James Fenimore Cooper, and the German writer Karl May—who never visited America and never saw an Indian.

—Doctor Eduard Bloch

“My Patient Hitler”

Collier’s, March 15, 1941

Elisabeth felt pleasantly lightheaded, and was enjoying, especially, the acute physical awareness she had of her tongue: the feathery ways it touched her teeth when she spoke—the soothing ways it pressed against the soft upper palate behind her teeth.

The tongue, she reminded herself, consisted of symmetrical halves separated by a fibrous septum, each half composed of muscular fibers arranged in non-symmetrical patterns, the fibers containing masses of interposed fat that were fed by a large number of vessels and nerves. The tongue also contained mucous and serous glands, and the mucous glands, she remembered, were uniquely similar to the labial glands. Could this, she mused, be yet another proof of what doctors often referred to as “the wisdom of the body”?

She was seated across from Doctor Bloch near a window in Manfred’s Tavern. The tavern was full—waiters in tuxedos and serving girls in brightly colored peasant dresses moved about busily—and Elisabeth looked away from the room and through the window where, across Long Island Sound, faint pinpoints of light flickered on City Island.

Manfred’s Tavern was situated along a coast road in the Throggs Neck section of the Bronx, and City Island, a fishing village with a large Italian population, was closest to land. She knew that Bellevue Hospital, acting as a depot for several city hospitals, shipped some two hundred corpses a week, along with wooden boxes filled with amputated arms and legs, to Hart’s Island, which lay a few miles north of City Island. There, the plain pine coffins were laid three deep in the ground. Nearer to shore, a half-mile east of City Island, was Rat Island, which had become a resort for vacationers.

How misnamed these places were, she thought: City Island was not physically part of the city; Rat Island was too rocky to house rats; and Hart Island, where the dead had no one to mourn for them, was a place without heart. Still, it felt wonderful to be here with Doctor Bloch, and to feel hopeful. Professor Max Brödel, the man for whom Elisabeth worked as a medical illustrator at the Johns Hopkins Hospital and School of Medicine—Brödel was a German émigré who had introduced the discipline of medical illustration into the United States—had suggested that Bloch, recently arrived from Austria, might be of assistance to Elisabeth in securing a visa for Elisabeth’s father. Her father, a widower, lived by himself in Vienna, where, as for all Jews there, life was becoming more difficult each day.

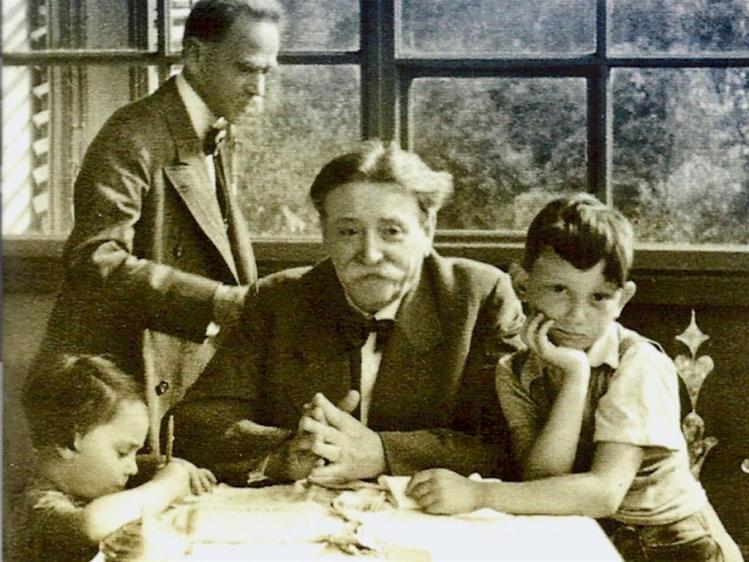

Bloch had been Adolf Hitler’s doctor when Hitler was a boy, had attended to Hitler’s family during the boy’s growing up, and to Hitler’s mother during her illness and death from breast cancer. According to Brödel—the professor was friends with Bloch’s nephew John, a physician who worked in Washington, D.C.—Bloch had been able to get out of Austria due to an unprecedented act: the intervention of Hitler himself, the only Jew for whom the German dictator had thus far performed such a service.

“I can only repeat what I have previously told you,” Bloch was saying, “which is that I did nothing to solicit the privilege that has made possible the personal liberty I enjoy on these shores, along with—equally important—the good fortune that has enabled me to meet you, though I sense that when I make such a remark, you are determined not to acknowledge its sentiment.”

“Au contraire, my dear doctor,” Elisabeth said, and she leaned forward, beckoning with her index finger for him to come closer. When he did, she kissed him, letting her mouth linger on his, letting her tongue touch his teeth through the narrow opening between his lips. He tasted of wine, potatoes, tobacco.

“Tell me, Doctor Bloch,” she said. “Wouldn’t you like to take me away from all this?”

“I would.”

“I thought so. But where might we go, do you think—Vienna? Paris? Rome?”

“I hardly think we can visit such places at this time.”

“Warsaw then? Prague? Amsterdam? Berlin?”

“Baltimore seems more inviting, and more possible.”

Elisabeth sighed. “Well, wherever we went, we would hope to have my father join us. That’s understood, of course.”

“Of course.”

She saw herself walking arm in arm with Bloch in Baltimore, along Broadway, from the hospital to her apartment, then inviting him in, serving him wine, taking him into her bedroom. His touch, she imagined, would be gentle, and it occurred to her, and in a way that was not unpleasant, that the hands that might soon be caressing her were the same hands that had once touched Adolf Hitler’s private parts.

In the restroom, an elderly woman in a black-and-white maid’s uniform stood, curtsied, and handed Elisabeth a warm towel. She spoke to Elisabeth in German, telling her that her name was Frau Giesler, and that she wished Elisabeth all good things for the holidays. Elisabeth noticed several photographs propped against the wall at one end of the marble countertop, and, thinking it would please Frau Giesler, she asked about them.

Frau Giesler said they were photographs of her children and grandchildren: three sons, two daughters, seven grandchildren. Elisabeth pointed to a photograph of a man in military uniform. Your son? she asked, and Frau Giesler laughed and said that this was a photograph of her husband, Otto, who had died in Germany nine years before. They had grown up together in the city of Mannheim, and had been childhood sweethearts. Had Elisabeth been to Manfred’s Tavern before? Frau Giesler asked. Elisabeth replied that she was familiar with the area, but that this was her first time at Manfred’s Tavern. She was having dinner with a friend, an Austrian physician recently arrived in America, she said, after which she excused herself, and entered one of the stalls.

When she emerged, Frau Giesler curtsied again, turned on a faucet, and gave Elisabeth a fresh, warm towel. Wasn’t it wonderful, Frau Giesler said, to be able to celebrate the Christmas season in an authentic German atmosphere? It was, Elisabeth replied, and added that it must be gratifying for Frau Giesler to see that most of the ways in which Americans celebrated Christmas derived from German traditions. Oh yes! Frau Giesler responded while she brushed Elisabeth’s dress lightly. Elisabeth considered the hours Frau Giesler, mother of five and grandmother of seven, spent by herself in a narrow room that smelled, with excessive sweetness, of lavender, and she wondered: Was this what she had come across the ocean for?

Frau Giesler asked if Elisabeth would like to try some of the tavern’s eau de cologne, which, she said, really did come from Cologne. “Please,” Elisabeth said, and closed her eyes while Frau Giesler gently lifted Elisabeth’s hair and sprayed cool mist on the back of her neck. Would Elisabeth like to try some of the tavern’s hand cream, which came from Müllheim, a city in the Black Forest not far from Freiburg?

Elisabeth spread her palms upwards so that Frau Giesler could dispense cream onto her hands. She smelled violets now, and something more pungent—verbena? thyme? lily-of-the-valley? She enjoyed being pampered, and she wondered: Was Frau Giesler going to offer her a massage? A bath in black mud? A manicure? A pedicure? Was she going to invite her home for the holidays?

“You have been most kind,” Elisabeth said, and she set a dollar bill on the counter beside the photographs. Without looking at the dollar bill or thanking her for it, Frau Giesler asked if Elisabeth lived in New York City, or was she merely visiting, and did she intend to return to Germany when that became possible? Only Frau Giesler’s eldest son, his wife, and their two children were here in America, she said. The others had stayed in Germany, where her two other sons and three of her grandchildren were now serving in the Army.

Elisabeth was about to tell Frau Giesler that she was Austrian, not German, when Frau Giesler whispered words Elisabeth was not sure she wanted to understand. She asked Frau Giesler to repeat what she said. Frau Giesler came closer and, her hand on Elisabeth’s hand, said again that what made things so special at this time of year—something, as two German women, they could appreciate—was that although they were in America, here at Manfred’s Tavern they could celebrate the holiday in the old way and in a place where they would not encounter Jews.

“But I’m Jewish,” Elisabeth said.

Frau Giesler said that clearly, in addition to being gracious and beautiful, Elisabeth was also possessed of a distinctive sense of humor—a kind of German humor Americans did not often understand.

“Otto—my husband, not my son—had that kind of humor,” Frau Giesler said. “Still, it is good to be here now—to have this work—but it will be better still, I think, when we can return home.”

Elisabeth felt momentarily confused. If she insisted to Frau Giesler that she was a Jew, what, other than hostility and resentment, would be gained? Should she reach into her handbag and give Frau Giesler even more money? And if she did, would such a gesture be seen as profligate—would it prove to Frau Giesler that she was, or that she was not, a Jew? And were this woman to be persuaded that she had been deceived about Elisabeth’s identity, what in her, or in Elisabeth—or in the world!—would change? Elisabeth considered saying that although her mother and father were Jewish, she of course was not, but she feared that such irony—any irony—would be lost on the woman.

More: she sensed that what she was most upset about was not the woman’s anti-Semitism, which seemed common enough, but the fact that what had been a nearly perfect evening, and what, if in a woman’s restroom, had just been a few moments in time that were blissfully out of time—simple, luxurious, and meaningless—had been sullied by the woman’s stupidity.

For a brief instant, she imagined that her father, overhearing the conversation from the other side of a wall—from the men’s restroom—was standing in the doorway, glaring at Frau Giesler. In her mind, she saw her father bow to Frau Giesler, then slap her hard across the cheek. The imagined sound, like that of a sapling being snapped in two, made Elisabeth wince.

“I have had too much to drink,” Elisabeth said. “But you have made me sober, Frau Giesler, and for that I thank you. I am a Jew—a Jewess, yes?—and I am spending a romantic evening here tonight with a dear friend—a physician of Austrian descent who, like me, is also a Jew.”

Without waiting to see or hear Frau Giesler’s reaction, Elisabeth left the restroom. There was no response, she knew, that would satisfy, though the scene in which she had imagined her father taking part had been accompanied by a fleeting desire to tell Frau Giesler who Doctor Bloch’s most famous patient had been, and she wondered if, later that evening, she would tell Bloch what it was that she had imagined.