It is regrettable, though perhaps not entirely surprising, that the Black artist Elizabeth Catlett is not better known: unsurprising because Catlett came of age in a time when women of color were marginalized as a matter of course, regrettable because of the power of her work, in which theme and medium are so closely aligned as to suggest destiny. Her subjects, mostly women, appear to have awaited not only Catlett herself, but also the particular tools and materials she chose, to bring them into being. Thankfully, a major new retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum, mounted in partnership with the National Gallery of Art in Washington, offers a necessary and fascinating corrective. In the more than two hundred works on view through January 19, 2025—be it linocut, painting, or, especially, sculpture—the side of life Catlett portrays informs her method of creation, lending each piece a feeling of inevitability.

In a lifetime that encompassed events from the First World War to the election of the first Black American president, Catlett (1915–2012) witnessed not only decades of racism but also the resilience with which it was met, a theme uniting her works across media and across time. A feminist, activist, and artist, she embodied that resilience in her own life. Catlett was born in Washington D.C. and studied at that city’s famed Howard University. In the mid-1940s, in a life-defining move, she spent the second year of her Julius Rosenwald Foundation grant working in Mexico as a resident at the Taller de Gráfica Popular (TGP), a center for collaboration among artists from around the world. With its focus on printmaking projects and political consciousness, the TGP worked to create art—in the form of prints, posters, and pamphlets—that was affordable and accessible for all.

Catlett’s political views were aligned with those of the other artists, many of whom belonged to Mexico’s Communist Party. During that period, Catlett was also influenced by the work of figures including her journalist friend Marvel Cooke and the civil-rights leader Ella Baker. Both wrote about the plight of Black women domestic workers in New York City, whose intolerable working conditions included not only unconscionably long hours but the threat of sexual violation.

Catlett’s feminism and concern for Black women workers informed some of her most powerful work. The exhibition includes pieces from her series The Negro Woman (which she later renamed The Black Woman). Many of these pieces are linocuts, a medium in which designs are etched into linoleum blocks and transferred to paper, mostly in black and white. Indeed, in her work as in life more broadly, blackness informs white space. If a nation is defined by the experiences of its least-well-off citizens, then the lives of the Black women depicted here amount to a critical comment on the predominantly white society in which they toil.

Among the most striking features of Catlett’s female subjects are their extra-long arms and extra-big hands, perhaps symbolizing the resources they bring to jobs that demand too much of them. In I Have Always Worked Hard in America, a linocut from 1946, three different women—or perhaps three versions of the same woman—work with a rag and bucket, scrub the floor on hands and knees, and wring out water. The figures are rendered in mostly vertical black lines, while the floor and nearby stairs are defined horizontally, creating—or reflecting—a tension between worker and workplace. A different kind of tension pervades I Have Given the World My Songs (1947). Here, Catlett renders a large-bodied woman in black lines who plays a guitar; behind her, in lighter tones, we see the subject of the woman’s songs: a hooded white figure assaults a Black man.

Perhaps nowhere is Catlett’s use of the vertical and the horizontal and of augmented body parts employed more powerfully than in her 1946 work portraying the iconic Harriet Tubman, who helped hundreds escape slavery. In this work, Tubman towers above the men and women she is leading, her extra-long arm pointing to a destination she can see, but we cannot: freedom. Catlett achieves similar effects in her 1947 linocut depicting the abolitionist and women’s-rights activist Sojourner Truth, who is shown alone, her emphatically upright figure filling the entire frame, a finger of one enormous hand pointing skyward, the other hand a steadying presence, holding the edge of a table where a Bible lies open. That and some of Catlett’s other linocut works feature a subtle interplay between white areas defined by black lines and darker spaces given shape by white lines. Insert your own metaphor here.

If the stark contrasts of Catlett’s linocuts are effective in portraying the public personas of these women—the work they perform, their obvious strength—her sculptures seem more capable of capturing something of who these women were inside. An inherent feature of sculpture is that it can be viewed from many angles, a fitting medium for depicting subjects in their full humanity. The stunningly beautiful terracotta Young Girl (1946) consists of the girl’s head and (very long) neck. Her wide-set eyes and slightly furrowed brow lend the work a haunted, and haunting, quality. Another sculpture, Tired (1946), one of the most affecting works in the exhibition, shows a seated woman with her hair in a bun. Her skirt acts as a kind of hammock for her clasped hands, which rest between her knees. She slumps just slightly, her head held at a forlorn angle. Our impulse is to comfort her, if we could possibly find the words. But maybe she wouldn’t need them. Tired and Young Girl both reveal the strength of Black women, powerful even when the world is not

watching.

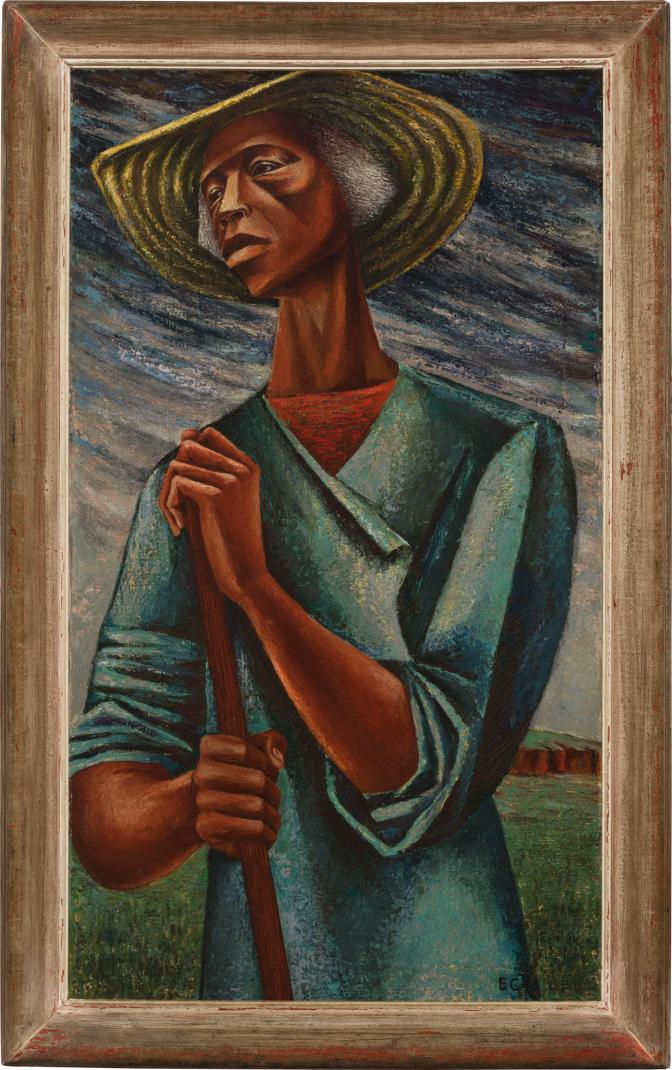

The paintings in the exhibition are relatively few, but suggest a happy meeting ground between Catlett’s linocuts and her sculpture. Sharecropper (1946) portrays a white-haired woman standing in a field, wearing a hat to protect her from the sun. She holds the handle of a hoe or rake and gazes into the distance. As with Catlett’s linocut of Sojourner Truth, here the woman’s body fills the frame; her neck, too, is very long, with prominent muscles forming a V. But Sharecropper doesn’t just show a woman performing her role in the world. The painting is also sculptural, both in the way it suggests the planes of this aging woman’s face and in the way it captures her inner life. We cannot see what she is gazing at, because she is looking inward. The sky and clouds behind her reflect the gray and white of her hair, while the clouds’ slanting lines meet resistance in the curving lines of the ridges in her sun hat. Perhaps the hat, yellow, is the sun, with any brightness in this landscape coming from the woman herself. Her dress is green like the grass behind her. She is of this world but also stands above it.

By contrast, the figure in the painting Working Woman (1947) is shown indoors, but she, too, has outsized body parts—large hands, long neck—and holds the handle of a tool, perhaps a broom or mop. She has also paused in her work and is gazing at something beyond the frame. She is younger, her dark hair in a bun; whereas the sharecropper may be looking at what has passed, perhaps this young woman is looking at what is ahead of her. What does her future hold? The large piece of furniture behind her, a different shade of brown from her skin, suggests domesticity (or domestic service), even as its drawers hold things that neither the woman nor the viewer can see. In one beautifully rendered hand, she clutches a cleaning cloth that is the same white as the garment she wears under her sleeveless blue housedress; in the eyes of the world, she and her labor are one.

The woman in the painting Untitled (1947) is shown only from the neck up. Like the figure in Sharecropper, she wears a hat, but of a very different sort. Small and olive green, it is meant not for protection, but for style. Like the Working Woman, she appears to be young. She is, from what we can tell, normally proportioned. In this way, and with her job unclear, the painting has left the linocuts behind. The woman’s most prominent features are her eyes, not abnormally large but prominent, looking away from us. With her eyebrows and closed mouth, the eyes form a serious expression, a suggestion of thoughts we cannot know. Her face is made to look three-dimensional, like a sculpture; she is both real and mysterious.

Catlett made a life in Mexico, marrying fellow artist Francisco Mora, with whom she had a long, loving union and raised three sons. In the 1998 film Betty y Pancho, included in the exhibition and directed by the couple’s son Juan Mora Catlett, the eighty-year-old Catlett notes that she realized she could create work for her people as Mexican artists did for theirs.

Then, she adds, Mexicans became her people, too. Indeed, Catlett’s art, which was of a piece with her politics, embraced the causes of Mexicans, Black Americans, and all others around the world who were subject to Western imperialism. Like many Mexican artists and activists, Catlett championed literacy, which she equated with power—as in the finely detailed 1953 lithograph Alfabetización (Literacy), which depicts three women wearing traditional dresses and sitting on the floor or ground, one reading to the others from a book. For Catlett, the political did not preclude the emotional. One of the listeners, the only one whose whole face we can see, looks touchingly earnest—serious, maybe a little worried, working to understand.

Catlett’s political stances and her association with the TGP got her and other members blacklisted by the U.S. government. Upon being denied a visa to enter the United States (Catlett had become a Mexican citizen), she said in 1970 that the American government feared she “constituted a threat to the well-being of the United States of America.” It is from this address that the exhibition takes its title. Catlett was defiant: “To the degree and in the proportion that the United States constitute a threat to Black People, to that degree and more, do I hope I have earned that honor. For I have been, and am currently, and always hope to be a Black Revolutionary Artist, and all that it implies!”

Catlett’s Black revolutionary spirit did not compromise her feminism. After reading the Black Panthers leader Eldridge Cleaver’s book Soul on Ice (1968), which laid bare his misogyny, Catlett created the work Homage to the Panthers (1970), a linocut showing, among other things, the faces of Huey Newton and Bobby Seale—but not Cleaver.

With Catlett’s reputation growing in the 1970s and ’80s, she was commissioned to create public artworks in the ensuing decades, including the intriguing sculpture Floating Family (1995–96), made for the Legler branch of the Chicago Public Library. The work depicts a mother and daughter whose hands meet in midair. At the Brooklyn exhibition, the figures’ shadows arguably create a second work.

One room of the show contains a platform with fourteen sculptures of women spanning four decades, from the late 1960s to the late 2000s. They include Figura (Figure, 1962), showing a nude woman from the knees up, one arm cradling the other, her head turned to the side. If we stand directly in front of that work, the woman seems unaware of our presence; if we move to the side of it, perhaps she sees us—but doesn’t care. She is not here for us.

The sculpture El Abrazo (The Embrace, 2010–17), one of the final works of Catlett’s career, completed with help from her son David Mora Catlett, shows a couple side by side, hugging. The man and woman love each other and are of equal stature. Catlett’s long life and career could not have concluded on a more appropriate note.

This article was published in Commonweal’s hundredth-anniversary issue, November 2024.