[This article was first published in the October 8, 1999 issue of Commonweal]

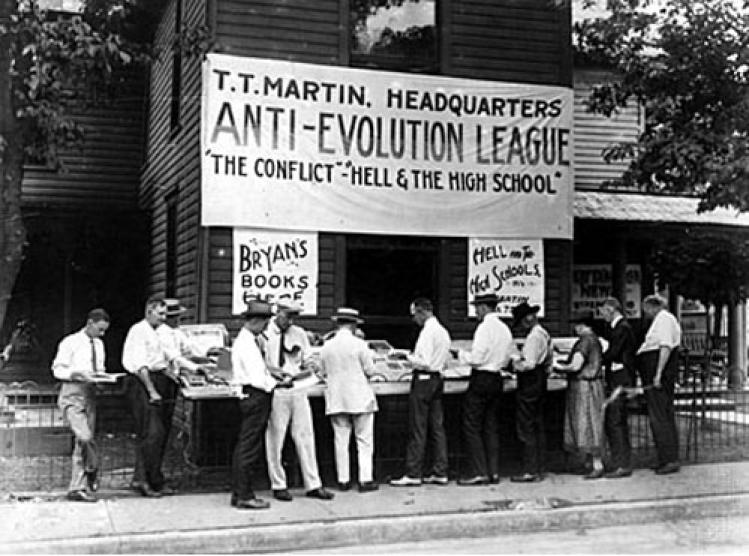

When the Kansas Board of Education voted this summer to remove overt references to the theory of evolution from that state’s science curriculum, specters of Tennessee’s “Monkey Trial” reappeared. The media had a field day--as they had the first time--writing about ignorant bumpkins who were again presuming to rule on scientific matters well beyond their expertise. The original Monkey Trial was indeed historic and important--but not for the reasons given in the media then or now. As Harvard paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould recently wrote, “The usual reading of the trial as an epic struggle between benighted Yahooism and resplendent virtue simply cannot suffice--however strongly this impression has been fostered.”

The Scopes trial never was a real criminal trial, with a real criminal defendant in any serious jeopardy of the consequences of his conviction. The entire case was a set-up-- and a vivid example of what can go wrong when set-up cases are allowed to proceed.

The American Civil Liberties Union, founded during World War I, had advertised throughout Tennessee for a teacher willing to make a “friendly challenge” to Tennessee’s law forbidding the teaching of evolution. John T. Scopes, a football coach and part-time physics teacher, volunteered. Scopes was not your usual football coach. With his tiny horn-rimmed glasses, white shirt and tie, and sincere expression, he looked like a young professor. Indeed, he had first learned about evolution as a student at the University of Kentucky, whose president led a pro-evolution fight. After the trial, Scopes went on to earn a Ph.D. in geology at the University of Chicago.

Scopes pointed out to the ACLU that he had probably never actually taught the offending ideas, although he had used the offending textbook, G. W. Hunter’s A Civic Biology, to help students review for a test. Much of the contents of A Civic Biology would be shocking to Americans today. For one thing, notes historian Edward J. Larson, the book was “heavily laced with the scientific racism of the day.” Human beings evolved from simple forms of life, with Caucasians being “finally, the highest type of all.” Negroes were the lowest.

Like many of the scientists arguing the merits of biological Darwinism, Hunter discussed eugenics (the science of improving the quality of the human race) as hard science. By 1925, the year of the Scopes trial, thirty-five states had passed laws compelling the sexual segregation and sterilization of those regarded as eugenically unfit--those who were retarded, mentally ill, and epileptic. In his textbook, Hunter casually wrote that “If such people were lower animals, we would probably kill them off to prevent them from spreading. Humanity will not allow this, but we do have the remedy of separating the sexes in asylums or other places and in various ways preventing intermarriage and the possibility of perpetuating such a low and degenerate race.”

William Jennings Bryan, one of the prosecutors in the Scopes trial and a man portrayed as a buffoon in the play Inherit the Wind, believed that World War I had in part been caused by Darwinian thinking. Many years before Hitler, Bryan railed about the brutality of eugenics, whose ugly implications were as important as biological Darwinism to the intellectual context of the Scopes trial.

Nonetheless, the facts of the trial itself were simple. A grand jury in Dayton, Tennessee, voted to indict John Scopes for violating a state statute outlawing the teaching of evolution. Presiding Judge John T. Raulston read both the statute and the entire first chapter of Genesis aloud to the grand jury. He virtually directed an indictment: “If you find that the statute has been thus violated you should indict the guilty party promptly. You will bear in mind that in this investigation you are not interested to inquire into the policy or wisdom of this legislation.” In other words, the jury was not to judge the law, only whether Scopes had violated it. So instructed, they returned an indictment before noon. The grand jury’s foreman, according to Larson, was a retired mine manager who later told reporters he believed in evolution. Given the judge’s charge, the foreman felt he had no choice but to indict Scopes for violating the law.

Raulston moved quickly to put the case before the trial jury. Jury selection took only a few hours. Although flamboyant defense attorney Clarence Darrow was known for taking days to select a jury, he did not bother in this case. His purpose was not to get his client acquitted. Rather, it was to get the case to a federal court while showing the public-at- large the depth of ignorance in Tennessee. Building on Darrow’s well-known view that Christianity was a “slave religion,” the trial presented an opportunity for the forces of progress and modernism to triumph over fundamentalism and backwardness. Darrow’s audience was the world, not the jurors of Dayton.

The trial became a media circus, one of the first. Journalists came from major newspapers here and abroad, and transmitted their stories via radio lines that the judge permitted into the courthouse. The crowds were so great that the judge eventually moved the trial outside to the courthouse lawn. The jury barely sat. Larson estimates that over the week-long trial the jury was in the courtroom for no more than thirty minutes--the time the prosecution took to present its case. As is so often true today, the battle between prosecution and defense was played out not in front of the jury but before the judge, who ruled on the admissibility of evidence and the appropriateness of witnesses. Famous scientists from Harvard and the University of Chicago, who were excluded from the courtroom, testified to throngs of journalists outside that evolution was fundamental to an understanding of science.

Darrow asked the court to instruct the jury to find his client guilty. He did this in part to hold off the possibility of a hung jury, which would have halted his plans to challenge the law’s constitutionality in a higher court. Darrow did not ask the jury to consider its other choice--jury nullification, that is, to find the law itself unjust. Nullification would have been a far better outcome for the country. American juries have a long tradition of nullification, dating back to printer John Peter Zenger’s trial in 1735. Zenger had printed an article--whose facts were not contested-- criticizing the royal governor’s embezzlement. Because English law made criticizing government officials a felony, Zenger was clearly guilty of seditious libel. Arguing that a story could not be libel unless it was false, Zenger’s lawyer urged the jury to consider both law and facts. They did, and found Zenger not guilty, setting the precedent for the First Amendment.

In the mid-nineteenth century, however, some American judges began objecting to nullification, particularly by the many Northern juries that refused to convict abolitionists who had helped fugitive slaves. In renowned racial cases, juries were far more likely than judges to be on the side of what we would consider right today. In the Dred Scott case, for example, the jury in the second trial, held in Saint Louis in 1850, concluded that Dred Scott and his family should be free. Scott’s former owner appealed all the way to the Supreme Court, and won in a notorious decision that also said Negroes had no rights under the U.S. Constitution. In 1895, the Supreme Court condemned jury nullification, saying that it is the duty of juries “to take the law from the court and apply that law to the facts as they find them to be from the evidence.” This matter is far from settled in practice. Four states (Georgia, Indiana, Maryland, and Oregon) acknowledge jury nullification in their constitutions. Juries across the country refused to convict draft resisters during the Vietnam War. Over the last few years, many juries have refused to convict drug abusers under severe drug laws. In some capital cases, juries have refused to convict when the verdict meant execution.

But most judges try to make sure that juries follow the law---even if the law is foolish or excessive. Is this the best course? The Scopes trial is helpful here. Most commentators today seem to think that while Scopes was found guilty by the jury, his side somehow won subsequently. In fact, the defense was firmly outmaneuvered. The ACLU’s intent had been to take the case to the U.S. Supreme Court. Scopes hired Darrow over the objections of the ACLU, which rightly feared that he would not construct a careful case worthy of the Supreme Court.

Darrow made fun of both the jury and the judge, reiterating that he intended to get the case entirely out of the state and in front of a superior forum. Instead, in 1927, Tennessee’s own Supreme Court overruled the trial court on technical grounds, saying the judge erred in imposing the $100 fine without the jury’s consent. The court reversed the conviction, eliminated the fine, instructed the attorney general to dismiss the prosecution (nolle prosequi), and halted the legal drama. Darrow had nothing to appeal.

The law under which Scopes was prosecuted stood for another forty-two years. Tennessee textbooks were edited to exclude evolution. Worse, according to a study in Science magazine in 1974, publishers across the nation also expunged Darwin from textbooks, not wanting legal problems to interfere with sales.

The nation and its school children would have been better off had Darrow mounted a full defense and given the jury serious material to consider, enabling them to reflect and rule on the rightness of this particular prosecution under Tennessee law. With such a defense, the jury might have refused to convict, nullifying the law. Or, had the jury still convicted, a full defense might have given the ACLU a legitimate record on which to appeal, perhaps successfully. It would have been ironic, however, had science won its preeminent legal position based on a text most scientists would repudiate today.