G. K. Chesterton was GKC. William F. Buckley Jr. was WFB. Fr. Richard John Neuhaus—priest, writer, and public intellectual—was RJN. When, in the summer of 2003, I became an editor at his journal, First Things, I found it peculiar that most of my new colleagues actually referred to him as RJN. Early on I made up my mind to call him Fr. Neuhaus, come what may (initials were for the page, I thought, not for familiar conversation). It didn’t take long, though, for me to get used to hearing the house usage. If anyone could get away with that kind of alphabetic heraldry at the beginning of the twenty-first century, it was Fr. Neuhaus. Some of his contemporaries have written more than he did, and maybe a few have written better, but who has written so much so well? He was shamingly prolific. There were the hundreds of articles, including those he wrote for Commonweal in the 1960s and ’70s. There were the thirty-two books he wrote or edited, some of them, such as As I Lay Dying, already minor classics. And then there was his monthly column in First Things, “The Public Square,” which usually ran to more than ten thousand words. He was a force of nature—or, as he would put it, a piece of work.

G. K. Chesterton was GKC. William F. Buckley Jr. was WFB. Fr. Richard John Neuhaus—priest, writer, and public intellectual—was RJN. When, in the summer of 2003, I became an editor at his journal, First Things, I found it peculiar that most of my new colleagues actually referred to him as RJN. Early on I made up my mind to call him Fr. Neuhaus, come what may (initials were for the page, I thought, not for familiar conversation). It didn’t take long, though, for me to get used to hearing the house usage. If anyone could get away with that kind of alphabetic heraldry at the beginning of the twenty-first century, it was Fr. Neuhaus. Some of his contemporaries have written more than he did, and maybe a few have written better, but who has written so much so well? He was shamingly prolific. There were the hundreds of articles, including those he wrote for Commonweal in the 1960s and ’70s. There were the thirty-two books he wrote or edited, some of them, such as As I Lay Dying, already minor classics. And then there was his monthly column in First Things, “The Public Square,” which usually ran to more than ten thousand words. He was a force of nature—or, as he would put it, a piece of work.

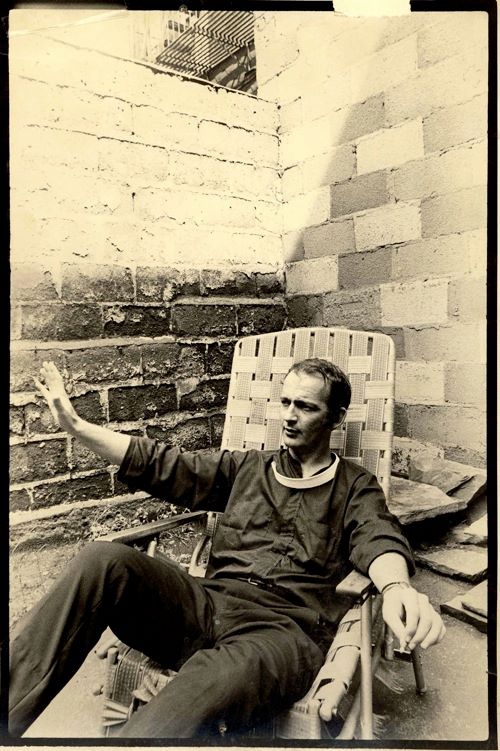

He was born and grew up in Pembroke, Ontario, the son of a Lutheran minister. He never finished high school and briefly ran a gas station in Texas before talking his way into Concordia Theological Seminary in St. Louis to train for the ministry. (Most of what he knew about literature, history, and philosophy he learned on his own. He was the most widely read—and least intellectually insecure—autodidact I’ve ever known.) Starting in the early ’60s, he served at St. John the Evangelist in Brooklyn, a mostly black Lutheran church, where he became active in the civil-rights movement. He marched in Selma with Martin Luther King Jr., and got himself arrested in New York at a sit-in for public-school integration. At the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, where he was a delegate for Senator Eugene McCarthy, he was arrested again, and tried for disorderly conduct. Later his politics shifted rightward, but he was always a radical, and always on the frontline. For him, there was never any conflict between activism and analysis; they were two aspects of a single engagement.

His involvement with interreligious and ecumenical dialogue led to several productive collaborations and close friendships—with Cardinal Avery Dulles, who was his sponsor when he entered the Catholic Church, and, earlier, with Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel. (Neuhaus and Heschel sometimes addressed each other as Father Heschel and Rabbi Neuhaus.) His interest in these dialogues was motivated partly by his natural love for conversation. He sought out anyone who might have something to teach him, and didn’t avoid people with whom he disagreed.

Of course, over the years he disagreed with a lot of people, including some with whom he had once agreed. He once wrote an essay titled “How I Became the Catholic I Was,” in which he argued that his embrace of the Catholic Church was the fulfillment, not the repudiation, of his Lutheran Christianity. He could have titled many of his later political essays “How I Became the Conservative I Was.” It’s tempting to detect a rationalization in this kind of rhetoric—a refusal to acknowledge that if he was right later on, then he must have been wrong before, or vice versa. But he had a right to that rhetoric, for the continuities it advertised were real. He really did believe in the fundamental, though imperfect, unity of all Christians; and he kept a quilted portrait of Martin Luther on his wall till the end. He really did believe that his commitment to the prolife cause was a natural and necessary extension of his commitment to equal rights for minorities. The common theme was justice, quickened by a Christian sense of solidarity. One didn’t have to agree with all his other political judgments to admire this purity of purpose. He never got bored with the prolife cause, and he never despaired of it.

His faults were as visible to his friends as to his critics. His many talents were obvious to anyone who read or heard him. But some of his virtues could be appreciated only at closer range. He was a movement man—he had a mind and a heart for movements—but he also had a great gift for friendship, and for personal loyalty. As he lay dying at Memorial Sloan-Kettering hospital, a restless phrase kept returning to his lips: “But I promised.” That was Fr. Neuhaus: a man unafraid to make big promises, and eager to keep them. RJN, RIP.