Some years ago, after I had converted to Christianity and become a Catholic, I had an abortion. I know the term “pro-choice” holds power for a lot of women, but not for me. I dislike it, because it speaks to the opposite of my own experience. I didn’t think I had a choice. Rather, the choice was made for me. To choose to keep my child would be a choice to lose everything else, including my home, my family, my larger community. I was being made to do something that went against everything I believed in. But I felt there was no alternative. And so I acquiesced, with the approval of all those around me.

In reality, I could have done something else. I could have dug in my heels. I could have said no. But I did not yet have the strength of character to do so. Back then, my God was a magical being, making no demands, fulfilling every wish. Concepts like “humility” and “sacrifice” were just words to me, and held only a negative connotation. So I believed it when people told me that having the baby would be selfish and would put a burden on others. “They are afraid of the little one, they are afraid of the unborn child, and the child must die because they don’t want to feed one more child, to educate one more child,” Mother Teresa once said. And I caved. I caved with tears and anger and resentment, but I caved. And when I woke up I felt utterly impoverished.

There were more falls and more mistakes before I found the way again. When I did, I was firm in my personal prolife stance. But I was also sure of something else. At the time of the abortion, I had been extremely vulnerable; even if it had been illegal, I might still have been pressured into having it done. And thus, I have never been able to ally myself politically with anti-abortion groups. For I know, on a very personal level, that women, for one reason or another, have always had abortions. For one reason or another, they always will. And when abortions are illegal, not only does the child die, but the woman might also be seriously injured or killed.

So there I was. Dismayed by the flippant attitude toward abortion expressed by my fellow progressives, but uncomfortable with the certainties expressed by the prolife movement.

As Christians, we often find ourselves in these liminal spaces of being, where we cannot be completely defined by one thing or another. The one thing we can define ourselves by is following Christ. Though it is often a grace in disguise, it can be hard going. How was I to ever honestly enter the debate on abortion? I couldn’t. I did, however, begin to share my story with young Catholics, both men and women. I talked with them as someone who had experienced an abortion, and also as someone who by then had gone on to experience motherhood. I talked to them about the sacredness of life.

I write anonymously for a number of reasons, which will begin to make themselves clear. I have to think about the privacy of my family, for one thing. But it’s also so that you might look at the women in your parish and know that they might be me—that this could very easily be their story too. I am not the only Catholic woman to bear these sorrows.

If Christians find themselves in liminal spaces, then so do women, only more so. We are never exactly where any part of society wants us to be. So was the case for me when, last year, I found out I was pregnant.

It was unexpected. Two years earlier, after giving birth to my youngest child, I had been fitted with an IUD. My pregnancies are hard; like the other women in my family, I suffer intense morning sickness. It’s significantly worsened by medication I need to treat mental illness, so much so that I have to reduce the dosage during pregnancy or risk hospitalization. Even so, while pregnant with my youngest, I was still sick multiple times a day for the first seven months. The doctors were worried: I was losing weight rather than gaining it. Once my son was born, it seemed advisable to go on birth control, although it was something I was reluctant to do. Part of it had to do with my Catholicism, but birth control also worsens the symptoms of my mental illness. Doctors suggested the IUD as an alternative, and several weeks later, it was placed inside my uterus.

IUDs are considered 99 percent effective. So the next pregnancy came as a surprise—yet it was not an unpleasant one. My husband and I had been married for well over a decade. An agnostic, my husband nonetheless went through the preparations for Catholic marriage, which of course includes the promise to be open to life. When we learned that a third child would be on the way, that our family would grow, we responded with joy. Of course, we were also worried about how to manage with another child, especially because I was about to begin a PhD in theology. But we’d been worried when as a college-aged couple we’d had our first, and we were worried as well when we’d had our second, while I was working on my master’s degree. Love enables us to make a way, even when things seem impractical, even when they might seem impossible.

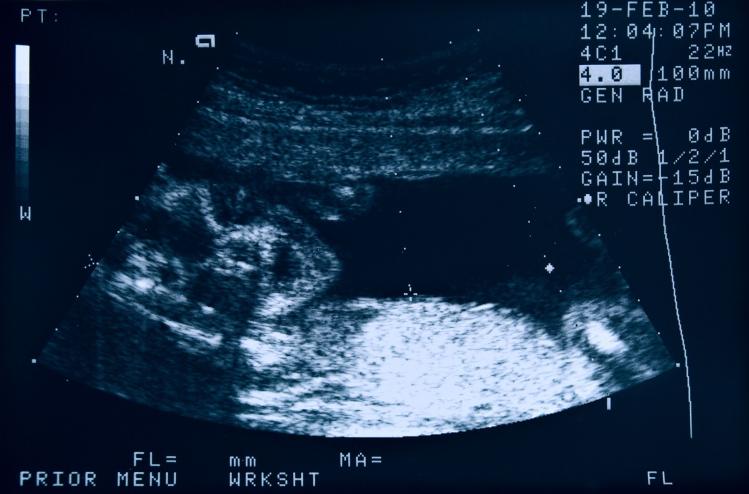

The doctors laughed when I called and told them I was pregnant. A baby conceived with an IUD must really want to be born, they said. I went in to have the IUD removed and to have my first ultrasound. I was the talk of the office. Jokes were made about my husband’s virility. All was well.

But then came the exam, which revealed that the IUD wasn’t there. The doctors said it had likely fallen out. If that was the case, then it wasn’t a surprise that I’d become pregnant. But there was another possibility. There was also a chance, an extremely small one, that the IUD had perforated my uterus. If this was the case, I was told, then the IUD would have to be located and removed, because it could cause serious complications during the pregnancy.

I underwent an internal and external ultrasound and two pelvic exams. The IUD could not be found. The doctors restated their belief that most likely it had fallen out, but it wasn’t something they could confirm. I could carry on with the pregnancy and assume that everything was okay, or I could get an x-ray exam. X-rays pose several dangers to a fetus, including a heightened risk of cancer later on; they can also cause miscarriages. But if the IUD had perforated the uterus and was still somewhere inside me, there could be fatal consequences for the unborn child—including preterm stillbirth.

Already, and completely unexpectedly, I was faced with a decision regarding the life or death of my child. Neither choice seemed better than the other. But I had a nagging feeling that the IUD was still in my body, so I went for the x-ray. And I was right.

The IUD had perforated my uterus, and there was no safe way to remove it before the baby was born. But I take openness to life seriously. Even knowing the risks, I would not abort. Not again. If the pregnancy failed, then that was something we would go through. For what of the person being formed inside me, with its own traits and talents and faults? What if this life was to continue to bloom? I knew my child already, simply in knowing its personhood. And in knowing my child, I loved my child, as much as I did my two sons already born. It was the same knowledge and love that allowed me to grieve over my abortion all those years before.

My husband was supportive, and despite his worries, was courageous in his support. But soon I started feeling pain in my abdomen, and I learned that just as the IUD could perforate my uterus, it could also perforate other organs in my body. While this is considered rare, I was already finding myself in a situation where the highly unusual had occurred. The dangers of an IUD floating freely in my abdomen were considered low, but not so low as to rule out complications that could be lethal to my child, and to me as well.

So there were several possibilities to consider. There was the possibility of a normal pregnancy and my giving birth to a healthy baby. There was the possibility of the child being born prematurely, not only surviving but also going on to thrive. There was the possibility of a stillbirth. There was the possibility of some other medical emergency. And there was the possibility of death—my own in addition to my child’s.

As a follower of Jesus, I am to follow him to the cross. The disciple is no greater than the master and my master ended his life on a cross. Was this my cross to carry to the end? Was even the possibility of this baby being born alive worth taking on the risk of serious illness and death? My immediate Christian response was yes. And then, I thought of my husband, and my children who were alive and well. And I could not do it. This time I made the decision to have an abortion.

Aware of my faith, the doctors didn’t call it that. They called it a “surgical procedure.” But I knew what it was. A dear friend and fellow Catholic told me afterward: “Don’t you dare call it an abortion because that is not what it was. You were in danger. Your child probably would have died anyway. What you did was merciful.” But I will call it an abortion because that is what it was. It was my choice . . . and yet at the same time, it was not. Sin, if I have learned anything in theology, is something we choose when we are not fully free. I take responsibility for this choice, and I recognize that the fact that this choice was one of the limited decisions I could make is evidence of a constraint on my own moral freedom.

I was awake during the abortion. If I had chosen general anesthesia, I would have had to wait another week, which seemed worse to me, both for my baby and myself. A volunteer doula was there; she held my hand and massaged my neck and held me. Before we began I had the two doctors, the nurse, and the doula stop for a moment of silence. I had my miraculous medal with me, and I said a Hail Mary out loud.

This story, I know, says as much about women’s experience with obstetrics as it does about religion and abortion. The reason I confess this experience here is to show how it encompasses far more than considerations of legality and illegality. The debates over the passing of abortion bans in several states do not do sufficient justice to the full experiences of women. I recoil at the oversimplifications coming from both sides. Abortion is, like so many things, a mainly pastoral issue. It is not as simple as legal or illegal, a personal right or an undeniable wrong. It is as simple as confronting the experiences of real women and hearing the voice of Jesus within their experiences of sex, childbirth, and, yes, the decision to terminate a pregnancy.

If all abortion is illegal, women will die. This is not debatable. It is a fact. Most people know this, and yet I understand as a Catholic that state-sanctioned killing—which I believe abortion to be—is more than problematic. I am not attempting here to convince anyone to change their political beliefs, but to break open their view of women’s experience of abortion itself. The need for abortion is evidence of our broken humanity, but our current response is also evidence of our church’s inability to respond fully to the female experience when there are no female voices.

At their best, prolife organizations affirm the grief and trauma felt by women recovering from abortion. They provide resources and direction for mothers and their unborn children, helping them not only survive but also thrive. Yet there are parts of the prolife movement that seem blind to other life issues, that in their actions and rhetoric can in fact seem hypocritical. I see certain American Catholics who don’t take in the entire seamless garment of life, and I wonder if their focus on the unborn is being used to distract attention from other policies that are prejudicial or even lethal. It seems in these cases that the bodies of infants are being used to hide such things.

This is not acceptable, and it demands that we must listen, as a church, to women. Not just to those women who say what we want to hear. Not just to those who echo our own visions of motherhood, or affirm society’s accepted version of it, or repeat our faith’s representation of it. Rather, we are called to embrace the entirety of female experience. Women in our churches—myself included, and I know that I am not alone—carry this burden in their hearts and remain unheard. So I ask you to hear my story, and not to turn away from it. Keep it in mind when you say your homilies and speak to your students. Keep it in your heart so that you may know how to minister and how to advocate.