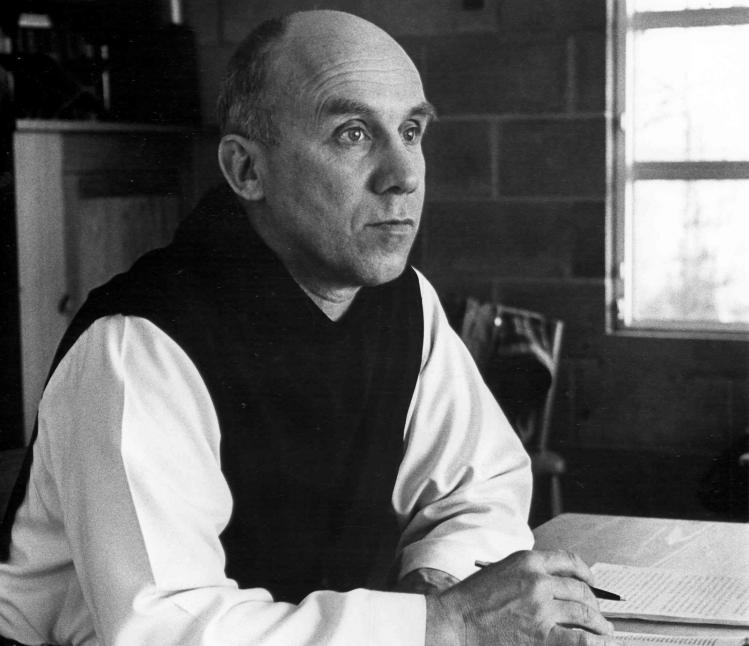

As the twentieth century recedes ever further into the past, Robert Hudson invites us to revisit it through an unexpected passageway: the troubled circumstances in which two of its most brilliant poets found themselves as the 1960s broke loose. Hudson calls The Monk’s Record Player: Thomas Merton, Bob Dylan, and the Perilous Summer of 1966 a “parallel biography,” but it’s weighted heavily toward Merton. And anyway, it’s really more a tale, a comic tale, of two men seeking a way through the age’s “baroque obscenities,” in Merton’s piquant phrase, to a place of solitude and hope.

The unlikely pairing of Dylan and Merton is the charm of the book. Merton and Dylan were a duo that never quite became a duet. They had no acquaintance, and so far as influence goes, it went in one direction. Merton, introduced to Dylan’s music in 1966 by a fellow monk, responded with instant affirmation in a letter to his editor. “Incidentally,” he wrote, “I heard a record of Bob Dylan lately and like him very much indeed. Respond extremely to that, very much at home in it.”

The record in which Merton felt himself at home was Highway 61 Revisited, and Merton’s “baroque obscenities” line was his description of the absurdist running commentary on the world beyond the gates of Eden Dylan was frenetically and gleefully dispatching. Merton was so taken with Dylan’s vision and approach that he quickly produced Cables to the Ace, Or Familiar Liturgies of Misunderstanding (1968), a book Hudson describes as a “long anti-poem” for which “Dylan’s work was the ongoing frame.” Hence Hudson’s arresting judgment: “although they lived their lives a thousand miles apart, their souls were next-door neighbors.”

The conditions that sparked such intimacy had to do with intimacy of another kind, and this now-familiar story is at the heart of Hudson’s tale. He tells it well. In Louisville for back surgery in the spring of 1966, Merton, age fifty-one, convalesced under the care of Margie Smith, a student nurse. She was half his age and engaged to a soldier, but their souls, too, established an easy company. “The sufferings of the soul that thirsts for God are blended with mystical joy,” Merton once said, and Margie infused no small amount of it into an aging, sojourning monk. For a season, in the spring and summer of ’66, Merton and Margie wrote, telephoned, and even, with the help of several accomplices, arranged the occasional rendezvous; Merton’s journals reveal that they managed over many weeks to talk by phone more than once every two days. Their predicament loomed embarrassingly large. What was a monk to do?

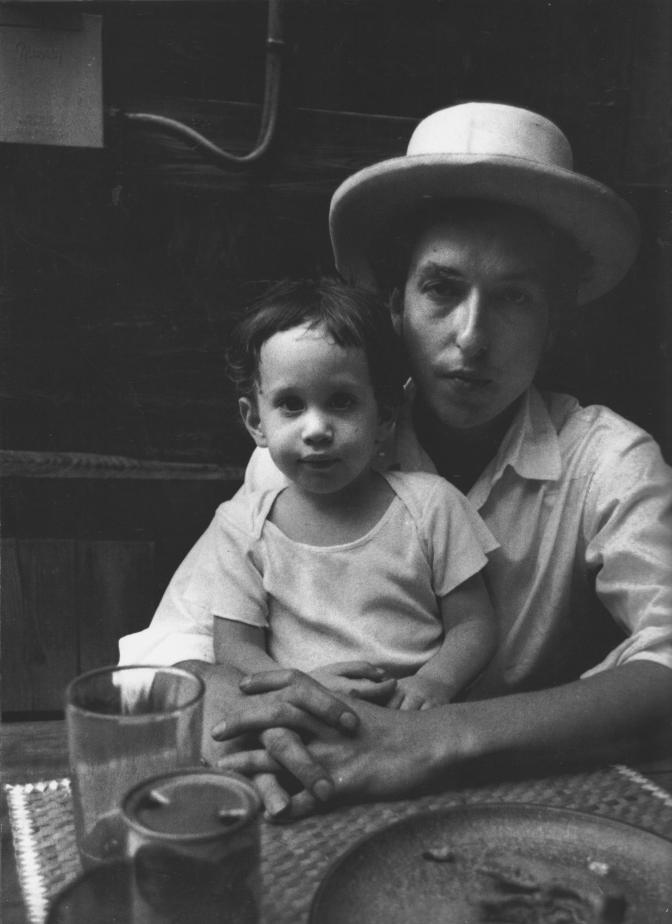

For his part, Dylan by that summer found himself in his own conundrum, one that also involved a kind of trap: fame. “Privacy is something you can sell,” he would wryly observe, “but you can’t buy it back.” He tried, though. Having loosed himself from the folk-music establishment the year before by, famously, going electric, he now wished, as Hudson says, “to go undercover and stop being Bob Dylan.” A mysterious motorcycle accident of uncertain severity became the pretext for his “own search for solitude.” And so Dylan would go underground for three years at his home in Woodstock, New York, writing and recording music, living convivially with family and friends, and avoiding the audience he had so assiduously sought. It sort of worked, for a time, Dylan’s “so-called hermit years.” But even his rural retreat became, as he put it, “a place of chaos”—its end symbolized by the cartoonish invasion in August 1969 of tens of thousands of young people in one of the age’s emblematic events. Solitude was very hard to come by, even in Woodstock. So was home.

Merton’s way of escape was more excruciating but in the end more satisfying. Having called Margie on one of the abbey’s party lines in June 1967, he was discovered, and quickly confessed to the abbot what he later would refer to, ambiguously, as his “affair.” He was met with sympathy but also strictures, and while he and Margie continued to sneak letters, phone calls, and an occasional meeting, by the end of July the affair was mostly over, with a final phone call occurring in November.

Merton felt acutely the absurdity of his situation—“a priest who has a woman,” he acidly wrote in a diary. But it was not simply the threat to his priestly vows that troubled him. Solitude had always been, in Hudson’s words, “his first love,” and marriage to Margie would certainly end it. The year before they met he had finally, after years of pleading, been given permission to live as a hermit at Gethsemani. It was a signal moment in his pilgrimage. For Merton, writes Hudson, “solitude was solidarity,” a gateway to love. “He who is alone and conscious of what solitude means,” Merton sensed, “finds himself simply in the ground of life. He is ‘in love.’”

These lines he had penned just before meeting Margie. But now, at the moment he had finally achieved solitude, he found himself doubly in love, discovering through Margie “a new kind of solidarity with the world,” as Hudson says. Still, in the end his vows and his calling—as celibate, hermit, and priest—retained their hold.

But not without—and most certainly with the aid of—Dylan’s mordant, tortured whispers, quicksilver in his mind and soul. Merton’s first mention of Dylan in his journals was the day of his June confession to the abbot. “Invisible. ‘Like a rolling stone,’” he wrote, cryptically. Both he and Dylan knew that the age—brash, boastful, obscene—was nonetheless inflamed with the kind of longing without which humanity turns grey. The catalog of madness Dylan was issuing was an honest telling, Merton could see; Dylan was “definitely conscious of a poetic vocation,” he thought. And no one was more conscious of that vocation’s necessity than Merton.

In perhaps the book’s most amusing vignette, Merton in October 1966 entertains the eminent and aged Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain at the hermitage, along with a few of his younger companions. Maritain and Merton, long friends, celebrate Mass and, with the others, settle around a fireplace, drinking coffee. The request soon comes for Merton to read some of his writing. He pulls out what will become Cables—followed hard by an earnest commendation of Dylan, whom he describes to Maritain—no mean aesthetician—as “a modern American Villon,” a reference to the wandering, path-breaking fifteenth-century French poet. But Merton doesn’t stop there. He fetches the abbey’s portable record player and spins some choice selections, “Mr. Tambourine Man” and “The Gates of Eden” among them—all for a man born in 1882! One of those present recounted that “played at full volume, the Dylan songs blasted the still atmosphere of Trappist lands with the wang-wang of guitars and voice at high amplification.”

It’s a fitting image of Merton as he neared his unsuspected final turn, his accidental death in 1968. In Cables he declared that “with the unending vroom vroom vroom of guitars we will all learn a new kind of obstinacy, together with massive lessons of irony and refusal.” Merton excelled at all three lessons. But if obstinacy, irony, and refusal served any purpose for him, it was to preserve hope, and most crucially, the hope of home: for that land where we were conceived in joy and will be welcomed in warmth, where our desires were born and will surely be met.

That hope provides the final destination for a book that is delightfully difficult to classify. Neither scholarly disquisition nor celebrity bio, it is rather history in the form of a fable: not dark but rather light comedy. It is light that illumines, finally, a direction home: through solemn vows, a solidarity born of forgiveness, and at least a touch of rock-and-roll.

The Monk’s Record Player

Thomas Merton, Bob Dylan, and the Perilous Summer of 1966

Robert Hudson

Eerdmans, $22.99, 263 pp.