Lumen fidei (The Light of Faith) is officially the first encyclical from Pope Francis but, as the document itself acknowledges, it is basically the work of his predecessor, Benedict XVI. Having written encyclicals on love (Deus caritas est) and hope (Spe salvi), Lumen fidei completes Benedict’s reflections on the cardinal virtues. The Church should be deeply grateful for the encyclicals that Benedict has written — and grateful for those he did not write. There were many who feared and many who hoped that the former head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, “God’s Rottweiler,” would issue highly directive admonitory letters castigating the errant within. While Benedict’s encyclicals are forthright in noting the dangers to faith from secularism and relativism, he wraps those concerns in profound meditations on the deep human need for a love and a hope that can be trusted.

When Benedict (as Joseph Ratzinger) published Jesus of Nazareth, I was asked to comment for a British publication on the question, “How will the book be received by the church?” That is a good question to ask about Lumen fidei. I have the sense that most churchgoers pay very little attention to encyclicals except on pointed moral topics or church discipline. There are many well-remembered examples of such papal writings: Gregory XVI’s Mirari vos, condemning liberalism; Pius X’s Pascendi, condemning modernism; and Paul VI ’s Humanae vitae, reasserting the ban on contraception. Benedict’s encyclicals are not in that common genre; they are ruminative, meditative reflections on the broadest and deepest themes of Christian life.

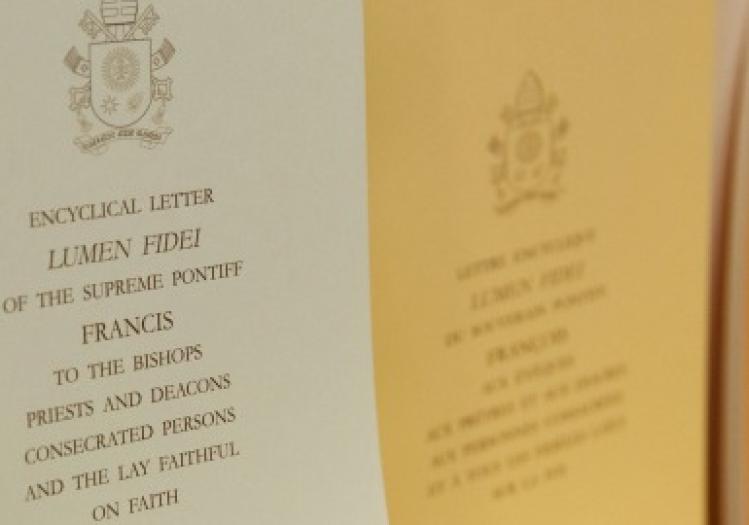

Officially Lumen fidei is addressed “to the bishops, priests, deacons, consecrated persons and the lay faithful.” If any of the above turn to the text they should be prepared for some hard thinking. A text that in two paragraphs moves from Wittgenstein to William of St. Thierry is not for the faint of heart and idle of mind. The account of the faith that emerges is complex and paradoxical. Faith is a light by which we see (lumen fidei), faith is a form of hearing (fides ex auditu), faith is touch, “what we have seen with our eyes and touched with our hands.” Faith exists only because love opens to truth beyond simple perception. Faith is sacramental. Faith is not individual and subjective; it is necessarily objective and communal; it must be “ecclesial.” Finally, in an unusual and oft repeated phrase, “faith is a process of gazing.” (Assuming that the original was written in German, the word translated “gaze” is Sichtweise, a manner of seeing. Faith is seeing in the manner that Christ sees.)

One could read the encyclical as a pious compendium of exalted phrases about faith: faith is love, life, destiny, hope, and so on. Given its provenance from a learned and dedicated pope, it might reassure the reader that one can cite Nietzsche, Rousseau, and Celsus and still believe — even though one doesn’t understand what it means or how it all fits together. Lumen fidei is not such a pious exercise; it is a profound statement, but one whose foundations are only hinted at in the textual superstructure. It is a document that needs to be read communally, paragraph by paragraph, followed by extended discussion on meaning and implication.

To the extent that I understand the foundational argument, the principal problem in Benedict’s treatment of faith is the quick linkage between faith as communal because rooted in love, to faith as ecclesial, to the magisterium, to apostolic succession. Frankly, even in the text, the latter elisions sound like a “deus ex machina” in the bad sense. “[T]he Lord gave his Church the gift of apostolic succession.” True enough, but the meaning of “apostolic succession” as it is interpreted institutionally is one of the most controverted issues in Christianity. Benedict is eloquent in his theology of ecclesia as a communion of individuals who do not lose individuality, but gain it through loving dialogue. In what way does the magisterium rise above a communion of dialogue? Does Benedict’s ecclesiology fit his theology?

Related: Final Chapter, First Words