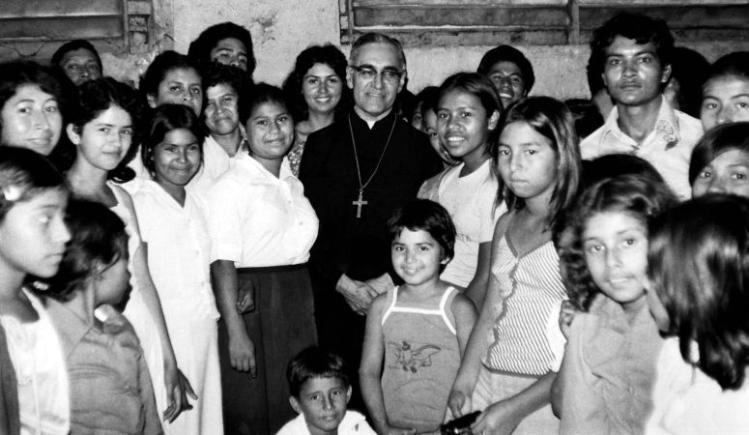

When Pope Francis announced in March 2015 that Oscar Romero, the slain Archbishop of San Salvador, would be beatified two months later, on May 23, I was in El Salvador on a mission trip with a group of students from Seton Hall University, where I teach. Excitement about the announcement was palpable: at the local church in San Miguel, where our group was stationed, the bishop saying our Mass that day must have mentioned Romero twenty times. Just four days earlier we had visited the Romero Center in San Salvador. There one can see the archbishop’s simple residence, which has been lovingly maintained by the sisters who run the cancer hospital where he lived and served. Pope Francis has called Romero a martyr, and the title is fitting. His death, which resulted from his courageous defense of those who were oppressed and terrorized by the government during El Salvador’s civil war, was not just a response to his “political” views, as some have argued. He was truly killed in odium fidei (“in hatred of the faith”)—a requirement for formal recognition as a Catholic martyr. A refusal on the part of some of his brother bishops to acknowledge this kept his cause from proceeding for many years. So it is a question worth revisiting: How and why is Romero a martyr? In what sense can it be said that he died for his faith?

We can find the beginning of an answer in the history of the church. When I heard Romero was scheduled to be beatified, I happened to be teaching the passion narrative of Perpetua, the young North African martyr, killed under the Roman government of Septimus Severus in 203 A.D. Perpetua, whose journal is the earliest surviving text by a Christian woman, tells of her imprisonment with six others, five catechumens and their teacher, Saturus, while they await execution in the arena at Carthage. A nursing mother, she wrote that her initial separation from her infant son caused her great suffering. Soon, however, she was allowed to be with him in her prison cell—until her distraught father finally chose not to bring the child to her anymore because, despite his pleas, she would not recant her faith. She and her companions, including two slaves, Felicity and Revocatus, shared prison, meals, and impending death with a profound faith and solidarity that challenged the class structures of the Roman world. Like so many of her fellow Christians, Perpetua and her companions were killed not for believing in Christ, but because they refused to offer sacrifice—in this case for the emperor’s son, Geta. This was interpreted by the Romans as a political and subversive act. Like Romero, Perpetua and her companions faced death with serenity. March 7, their feast day, was the day our group flew to El Salvador.

It was also the day we went to the Romero Center and saw his rooms, his desk with a Pietà and typewriter still on it, his bloody vestments from the day he was slain preserved in a glass wardrobe, his car keys and license and other personal items kept intact in the little museum that his house has become. We prayed in the church where he was killed, in front of the altar marked with a memorial of his death, and at the shrine outside his home, where the sisters secretly buried Romero’s organs, received after his autopsy. The rest of his body is buried in the cathedral of San Salvador. Praying at the church and the shrine, I believe we all sensed the sanctity permeating this place where Romero lived and prayed. Here was the desk where he had worked each day and night, the narrow bed where he had lain. He had known he might be killed at any time, yet he continued to speak out on behalf of the poor and the marginalized. He refused to make a sacrifice of his conscience to his country’s rulers and was therefore judged a subversive, like Perpetua. To be killed for doing right and speaking against evil in the name of Christ is to be a martyr.

MANY OTHER martyrs’ deaths have also been linked to “political” concerns, or at least to reasons not directly related to a specific hatred of the church as an institution. Another early example is St. Lawrence, who, according to legend, was ordered by the Romans to show them “the treasure of the church.” Lawrence, in a gesture connecting him to Romero, brought together many of the poorest Christians in Rome and presented them to the Romans. Infuriated, his Roman persecutors responded by burning him to death on a hot grill. Another martyr whose death was linked to political issues, “Good King Wenceslaus” (now known mostly because of a Christmas carol) was slain by his brother Boleslaw, who wanted to establish himself as king. Boleslaw was a pagan who wished to get rid of his brother, who sought to establish Christianity in their kingdom. Thomas Becket, the “holy blissful martir” who inspires the pilgrimage in The Canterbury Tales, was another bishop slain at the altar by people who considered themselves Catholic and believed they were punishing a traitor. According to legend, King Henry II asked, “Who will rid me of this troublesome priest?” and several of his henchmen volunteered.

Another Thomas faced off with another Henry several hundred years later, when King Henry VIII broke with Rome because the pope refused to annul his first marriage, to Queen Catherine of Aragon. When Sir Thomas More, who had been Henry’s friend, would not sign the act granting the king the title Head of the Church of England, More was beheaded. His execution, like Thomas Becket’s, was regarded by the king and his officials as the appropriate punishment for treason. They saw themselves as defending a just political order from foreign interference, and they saw More as one of the rebels (there were others, like Bishop John Fisher) who threatened the king’s authority. Today, even the Church of England honors More for having been true to his religious beliefs, for being a martyr. But at the time his killing was intricately linked to a political crisis.

Martyrdom, being an act of witness, always involves testifying to the truths of the faith, but as these cases show, the truths in question are not always purely theological. And the expression of those truths always has a historical context, and often a political one. As his beatification by Pope Francis affirms, Romero follows in a long and glorious tradition. In more recent years, among those declared martyrs there have been others whose deaths were the result of hatred not for the Catholic Church per se, but for the martyr’s personal witness to the values of the Gospel—and this, too, is odium fidei. Maximillian Kolbe, the priest killed in a Nazi concentration camp, willingly gave up his life for a fellow prisoner, the father of a family. Kolbe did as Jesus taught, laying down his life for a friend. Edith Stein, also known as Sr. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross, is honored by the church as a martyr even though she was sent to Auschwitz because of her Jewish heritage, not just because she was a nun. (In the Netherlands, where Stein was living, the Nazis targeted Jewish converts to Catholicism as part of their retaliation against the Dutch bishops, who had published a statement against Hitler.) In the end, Stein understood her Catholic faith to require solidarity with the Jewish people; her conversion was not a renunciation of her ancestry.

In the complexity of the modern world, where the nation-state came to occupy more and more space, martyrdom has often involved what appeared, from another perspective, to be subversion or treason. More is at stake than the motives of those responsible for a martyr’s death. Sometimes the value for which a martyr dies is the simple lived purity seen in the life of a saint like Maria Goretti, who was killed because of her courageous refusal to grant sexual favors to a neighboring youth. The young man who murdered her was not attacking “Catholicism,” but responding in frustration to her refusal of his advances. St. Maria’s clinging to her own purity, a value deeply honored in the Catholic faith, gives her death a religious significance her killer did not intend.

When Pope Francis unblocked Romero’s cause and, soon thereafter, set the date for his beatification, he was not only honoring the slain archbishop but also reminding the world that the preferential option for the poor, like other crucial spiritual and moral values, is an integral part of the Catholic faith—so much so that someone who dies for it is, in fact, a martyr. As Romero himself said, in a sermon delivered in May 1978, “A church that does not join the poor, in order to speak out from the side of the poor, against the injustices committed against them, is not the true church of Jesus Christ.” Romero was beatified because he not only spoke out from the side of the poor but was willing to lay down his life for them. His death is still speaking to us now.