When William Pfaff died in April 2015, his ashes were interred in Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. He had never given explicit instructions about the inscription for his final resting place, so the task of summing up his life and career fell to his son Nicholas. It was not an easy one. There was no single position or accomplishment that clearly captured Pfaff’s identity. He began his career as an editor of this magazine, going on to join the United States Army, and, during the early days of the Cold War, serve as a political-warfare officer. Then, after two decades in a think tank, he spent the last thirty-seven years of his life with no institutional affiliation, working as a columnist, a conference speaker, and even occasionally a teacher (although he considered himself particularly ill-suited for the job). Along the way he also wrote or co-wrote ten books.

If there was a common thread connecting each of these professional activities, it was his erudite foreign-affairs analysis. Yet Pfaff was no academic, never having obtained a degree beyond his BA from the University of Notre Dame. Nor was he comfortable with the word “intellectual,” which he found hollow and pretentious to the American ear. He did use a variation of the term, though, when he wrote about his sense of vocation in an essay originally published in Salmagundi and later included in 1987’s Best American Essays under the title “The Lay Intellectual: Apologia Pro Vita Sua.” If he was to be an intellectual, it was as an outsider, having undergone no official formation and taking no orders from the academic powers that be—an unconsecrated and self-motivated trafficker in ideas. “Lay intellectual” may have been the perfect phrase to capture his independent streak, but it was also far too unwieldy for a grave marker. Nicholas chose to focus on his father’s primary means of expression, his writing. Given his father’s inveterate Francophilia and long residence in Paris, the French word ultimately seemed most fitting: William Pfaff, Ecrivain, 1928–2015.

Columnists and commentators, unlike poets and novelists, are rarely read or remembered after their era. The memory of devoted readers fades and then disappears forever. The only new readers of yesterday’s analysis and debates are historians with their synthetic sweep. So while longtime Commonweal readers may remember Pfaff—his first piece appeared in this magazine in 1950 and his last almost sixty-five years later—he has largely faded from the general conversation. But for more than three decades in the pre-internet era, he was one of the most respected foreign-affairs commentators in the world. Pfaff’s columns on the op-ed page of the International Herald Tribune, the only paper that has ever had a legitimate claim to be the global paper of record, were read in boardrooms and embassies across the world. Former heads of government and future heads of state penned personal letters to him in response to his columns and books. He was a regular at Davos. And he had the privilege of writing for the greatest American magazine editors of the latter half of the twentieth century: Lewis Lapham at Harper’s, William Shawn at the New Yorker, and Robert Silvers at the New York Review of Books, among others. Pfaff corresponded with some of the greatest minds of his time—ambassadors, academics, politicians, journalists—and welcomed many of them into his sumptuous 7th-arrondissement Parisian apartment on the rue de Varenne, where he and his wife Carolyn would entertain them in style.

Örjan Berner, the Swedish ambassador to France during the 1980s and to the Soviet Union at the time of its collapse, numbered among them. Last year, Berner told me over the phone that Pfaff stood in the same company as George Kennan, the American diplomat who was the author of the United States’ Cold War containment policy. In Berner’s view, the two men were virtually unparalleled among Americans in their capacity to navigate the transatlantic divide. Berner was far from alone in his praise. In 1990, Jacques Chirac, then mayor of Paris, wrote Pfaff a letter after reading the French translation of Barbarian Sentiments, a critique of the global superpowers’ misreading of third-world nationalist movements. The mayor expressed his hope that more Americans would follow in Pfaff’s footsteps and deepen their knowledge of European affairs, because “the key to our two democracies’ enduring relationship resides most certainly in mutual understanding.” One of Pfaff’s most intriguing correspondents was Svetlana Alliluyeva, Joseph Stalin’s only daughter. In 1991, she wrote him a letter in response to one of his International Herald Tribune columns about the CIA, confirming his analysis and informing him that he was uniquely placed to understand her own story, which she then proceeded to recount in detail.

That Pfaff understood Europe well enough to generate this level of respect from European elites had much to do with his education. When Pfaff studied English at the University of Notre Dame in 1945, he entered a unique liberal-arts curriculum at a compelling moment in history. He began his university studies as a seventeen-year-old with the first wave of GIs returning from the war, at a university that had benefited greatly from the ideological ferment of the preceding decades. Not only had French and German-Catholic intellectuals enriched Notre Dame’s faculty roster over the course of the war, but the war’s human destruction had sharpened the usually abstract inquiry of the humanities around very real and palpable questions. In “The Lay Intellectual,” Pfaff describes “studying the Greeks, aesthetics, Dante, Shakespeare, Kierkegaard, Rimbaud and Baudelaire, Maritain, Bernanos, Mauriac, Hermann Broch, Romano Guardini.” It was not, he admitted, “a bad education to offer provincial boys from the Catholic immigration; but it was not exactly an education calculated for success in the American Dream.”

If his undergraduate degree didn’t prepare him for success in industry or finance, it most certainly prepared him for a lifetime of independent, critical inquiry. Perhaps most importantly, it familiarized him with the lessons that Europeans tend to draw from the history of the first half of the twentieth century—an understanding more tragic than triumphal. It thus comes as no surprise that Pfaff’s biggest and most recurrent criticism of his country’s foreign policy concerned America’s understanding of history. In his 2004 collection of columns about Afghanistan and Iraq, Fear, Anger and Failure, Pfaff quoted his first book The New Politics, cowritten with Edmund Stillman in 1961, noting that little had changed in the intervening four decades:

Here is our flaw: a defective sense of history, a refusal to acknowledge our implication in time. For whatever we think, history is flawed and uncertain and incalculable. And if the American nation makes it its mission to solve history’s riddle and bring time to a stop, it will wreck itself. That is what we are in danger of doing…. The American interest does not lie in clumsy para-empire or in the self-contradiction of ideologized democracy: the one is futile and the other a dangerous absurdity. We must remember that America is not exempted from the historical imperatives, the laws of life and decay. And the American destiny, whatever it may be, is certainly not to hold universal responsibility.

If his Notre Dame education was Pfaff’s crucial formative experience, his time at Commonweal came a close second. On the recommendation of a Notre Dame professor, longtime Commonweal editor Edward Skillin wrote Pfaff in 1949 to ask him if he would like to “try his hand” at journalism. Against his father’s wishes, Pfaff said yes and moved to New York, where he entered not just the world of journalism, but the churning intellectual milieu of postwar Manhattan. Throughout his life, when asked about the prestigious publications for which he had written, Pfaff would always compare them poorly with the collegial environment of Commonweal.

In the 1950s Pfaff cycled through several jobs: military service during the Korean War, a return to Commonweal, and then stints at ABC News and the Free Europe Committee. The latter was a CIA-funded outfit (a detail unknown to most at the time) that engaged in political warfare in Eastern Europe. In that capacity Pfaff met a number of politically involved exiles from behind the Iron Curtain. Eastern Europe became for him not just a battleground between communism and liberal democracy, but a place with history, religion, and culture, all attached to faces, names, and stories. With this background, it was simply impossible for him to accept that the Cold War was a Manichean struggle between the evil of Communism and the good of liberal democracy, or that politics could be reduced to the allegiance of each country’s government to one or the other.

One of his American colleagues at the Free Europe Committee was Edmund Stillman, a secular Jew from New York with similar literary, cultural, and political sensibilities. In 1960, they co-wrote a review of Herman Kahn’s On Thermonuclear War that bears all of what would become the hallmarks of Pfaff’s contrarian approach. Kahn’s method is “interesting,” they admitted, “but a severely limited one, employing a scientific method on materials that are not always susceptible to such analysis.” Those materials included “the true passions and motives in the lives of men and nations,” as they put it. “The Soviet Union is not governed by a digital computer, nor is the West.” Despite the critical nature of their review, it earned both Stillman and Pfaff employment at Kahn’s newly formed think tank, the Hudson Institute—then a big-tent institution with much more ideological diversity than its current neoconservative instantiation. In fact, for the rest of the 1960s Stillman and Pfaff served as the loyal opposition at the Hudson Institute. Where Kahn addressed the topic of thermonuclear war with almost clinical abstraction, Stillman and Pfaff insisted breezy discussions brought such war one step closer to reality. Where Kahn sought technological and game-theory solutions to political dilemmas, Stillman and Pfaff insisted on a more historically based approach that stressed the limits of American power and was more likely to advocate for political and diplomatic solutions to thorny conflicts in foreign affairs.

In The New Politics, the first of three books the two men wrote together, they took their cues from de Gaulle’s rise in France, the Sino-Soviet split, and nationalist revolts in Hungary, Poland, and Egypt, among other events of the 1950s, to argue for a new American politics for a multipolar world. They argued that Soviet Communism was a spent force politically, capable only of being an “eager second” to nationalist revolutions. The reviews were excellent, and President John F. Kennedy was even photographed with the book under his arm. A Rockefeller grant for a second book quickly followed. With the grant money, Pfaff traveled through Southeast Asia before meeting Stillman at the Rockefeller Foundation’s center near Italy’s Lake Como to work on what would become The Politics of Hysteria (1963). This time, the two friends placed the Cold War in the broader sweep of the West’s destructive penetration of the rest of the world. Many years later, the writer Pankaj Mishra discovered the book in a used-book store in India. He was amazed that two American men in the early 1960s had been capable of articulating this dynamic, so acutely felt in what was then called the Third World. Stillman and Pfaff’s third book, Power and Impotence (1966), critiqued America’s crusade against Communism, for which neither its history nor its character had prepared it. It was their most direct rebuke yet of the messianism and Manichaeism of American foreign policy.

A common thread running through Pfaff’s lifetime of writing was the violence of utopian ideologies. The obsession was as personal as it was historical. Stories of military valor and the pageantry of uniforms greatly interested him when he was a young boy. During his adolescence outside of Fort Benning, Georgia, he imbibed Southern notions of chivalry and honor. He was too young to enlist for World War II, but he did join ROTC, and then a few years later, when the Korean War broke out, he enlisted in the Army, eager for combat. The armistice ending the war was signed, however, just as he arrived in Eastern Asia to be deployed. So he returned to the world of journalism at Commonweal, and then, a few years later, he joined the Free Europe Committee, convinced that Stalin presented a unique threat to Europe. Throughout his life, he consistently defended his role preparing what was essentially political propaganda as a necessary measure. But he increasingly called into question his own country’s military posture. By the time he and Stillman wrote The New Politics in 1961, Pfaff had become largely skeptical that the United States’ Cold War measures were necessary. Pfaff was an early critic of the American role in Southeast Asia, for example. In 1962, he visited Vietnam, where he reported on American military operations, witnessing firsthand the gap between actual American activity in Vietnam and the U.S. government’s rhetoric. America’s seeming ignorance of Vietnam’s complex history of regional, ethnic, and religious conflict only confirmed his opposition to reductive Cold War binaries. From then on, he would urge restraint and prudence in American foreign policy.

As Pfaff grew increasingly vocal in his opposition to the American intervention in Vietnam, he became interested in what drove so many men to find redemption through violence. He had noted the influence of T. E. Lawrence on his own life, and he knew he was not the only one. Pfaff came to believe that the Western belief in progress, often to be achieved through supposedly redemptive violence, was a cause of some of the worst tragedies of the twentieth century. In 1966, he wrote a letter to his editor Alice Mayhew at Harper & Row proposing a book project about romantic violence, examining figures such as Lawrence, Andre Malraux, Ernst Jünger, Willi Münzenberg, Gabriele D’Annunzio, and Arthur Koestler. He would rework the idea time and again for four decades, but when the book was eventually published in 2005 as The Bullet’s Song, its structure followed the 1966 proposal almost exactly.

For much of the 1960s, though, Pfaff’s concern was with the misplaced violence of America’s intervention in Vietnam. The best example of Stillman and Pfaff’s disagreement with their colleagues at the Hudson Institute can be found in the 1968 publication of a debate titled “Can We Win in Vietnam?” Daniel Ellsberg, the RAND employee who later leaked the Pentagon Papers, wrote a thoughtful review of the debate. He praised the ideological diversity of the Hudson Institute, singling out Stillman and Pfaff’s contributions in particular, especially their emphasis on “factors of culture, politics, and history, and particularly on American limitations.” If this “neglected” point of view had been heeded, Ellsberg suggested, “we might have avoided an American tragedy.”

Eventually, their role as the in-house opposition at the Hudson Institute wore thin. Pfaff and Stillman felt a certain futility in their attempts to change public opinion or official policy. So when Kahn asked Stillman to found a European offshoot of the Hudson Institute, Stillman agreed but insisted it be based in Paris. Pfaff followed the next year, becoming deputy director. The two men, who met in a CIA-funded political-warfare outfit and struggled through the ’60s in opposition not just to their government’s policy but their own employer’s views, thus gained a new start in the French capital.

Of the many aspects of Parisian life that pleased Pfaff, foremost perhaps was the respect France offered its intellectuals. Because of its educational system and the centrality of Paris to all aspects of French life, there was a joint conversation that involved industry leaders, politicians, journalists, and academics. Pfaff was particularly taken by what were essentially economics lectures on national television by Prime Minister and Minister of the Economy Raymond Barre, an absolute impossibility in the United States. It was the tail end of the Trente Glorieuses, three decades of sustained economic growth following World War II. Pfaff and his colleagues at the Hudson Institute Europe saw only upsides for the French. In 1973, they published a report on the French economy titled Envol de la France that predicted these trends would continue. France, they argued, would clearly establish itself as the leading economic and political power of Western Europe. In retrospect, the analysis extrapolated too much from current trends, even if it did help turn attention to the real dynamism of the French economy.

Simultaneously, Pfaff was branching out into a solo writing career. Just before leaving for Paris in 1971, he published his first book without Stillman, Condemned to Freedom. It was excerpted in the New Yorker, whose editor William Shawn wrote Pfaff to say he looked forward to publishing more of his work. Thus began a twenty-year series of New Yorker articles on foreign affairs that ran under the banner “Reflections.” This enviable arrangement and the newfound prominence that came with it gave Pfaff margin for maneuver when he came into conflict with Stillman in 1978 over the management of the institute; Pfaff chose to quit.

This shift back to freelance journalism, which Pfaff would later characterize as the “wiser” course, involved more than just the New Yorker. He began a weekly column for the International Herald Tribune at the invitation of its editor Buddy Weiss, which Pfaff then self-syndicated across the United States. The Tribune was one of the first newspapers to use remote printing sites, and the first to achieve a truly global distribution network, placing itself at the elite end of the market. Pfaff’s columns were thus put in the hands of a growing number of international elites from the 1970s to the 1990s. This was the general situation in which Pfaff would write “The Lay Intellectual” in 1987: as a successful writer with a loyal following, independent of any institutional context. In the closing paragraph of that essay, he expressed an acute awareness that it might not last:

I cannot say that I am sorry, haphazard and hazardous as all this has so far been, and God only knows where it will end. Possibly it will end in a trailer park in Arizona like everybody else, or in a room without a view in Antibes with all those books we’ve accumulated. Possibly it will be at a university nonetheless, as happens to aged journalists, to become—I believe I have the right expression—a “resource person,” whom I take to be an elderly mariner or retired explorer propped up with a gin to tell repetitive tales of the cannibals and kookaburras of the cloistered world. Thus may the circle close and the irreconcilable to reconcile. I cannot say that I really look forward to it.

His greatest success, however, was still to come when, just two years later in 1989, Pfaff published Barbarian Sentiments: How the American Century Ends. Based on several of his New Yorker “Reflections” pieces, the book argued that there was a certain “intellectual confusion” in how both the United States and the USSR approached nationalist movements throughout the world. The fall of the Berlin Wall seemed to vindicate his thesis, and the book received abundant acclaim. The English version was a finalist for the National Book Award in the United States, and the French translation won the Jean-Jacques Rousseau award in Switzerland.

These were Pfaff’s glory years. Requests for speaking engagements and contributions rolled in. Former German chancellor Helmut Schmidt wrote him to comment on one of his columns. Former French President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing invited him to be on the panel of judges for the Prix Tocqueville. Singapore’s founder Lee Kuan Yew asked to meet him on a trip to Paris. Czech playwright and president Václav Havel invited him to be a speaker at Forum 2000. Pfaff’s columns were required reading for world leaders and his contributions on geopolitical debates were followed with deep interest. Another one of his books even found its way into the American president’s hands. The Wrath of Nations, Pfaff’s follow-up to Barbarian Sentiments, was a study of nationalism itself. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, a friend of Pfaff’s, gave a copy to Bill Clinton in the White House. As Moynihan later reported back to Pfaff, the president remarked, “He’s a pretty smart guy.” Moynihan, the one-time professor, promised to follow up with a quiz.

The universal acclaim, however, was not to last. Jacques Chirac’s parting comment on the importance of European-American mutual understanding in his 1990 letter proved to be prescient. Just over a decade later, in the run-up to George W. Bush’s invasion of Iraq, when Chirac was president of France, relations between the two countries dropped to historic postwar lows. Perhaps predictably, Pfaff found himself on the side of the French. “France,” he wrote in one of the columns published in his 2004 book Fear, Anger and Failure, “offers the only coherent and relevant modern model of constructive resistance to U.S. power: the Gaullist model.” In a country that had recently undergone the shock of 9/11, this was too much for many. Some viewed Pfaff’s criticism of Bush’s plans to invade Iraq as treasonous. Bill O’Reilly devoted a ten-minute segment on Fox News to one of Pfaff’s columns, denouncing him as out of touch and anti-American. If his analysis has held up much better than anything O’Reilly had to say on the matter, it was also true that Pfaff had grown distant from the American sentiment during his many years abroad.

Whether because of his principled criticism of Bush’s “Global War on Terror” or because of the sector-wide decline in journalism, many longtime subscribers to his syndicated column stopped publishing it altogether. The International Herald Tribune, which had been acquired in full by the New York Times in 2002, also stopped publishing his columns having to do with American foreign policy. Pfaff continued to explore the themes he always had, but the American political and media context had altered greatly by the early 2000s. His voice, long a respected—if also ignored—staple in American debates over foreign affairs, was now pushed to the political margins.

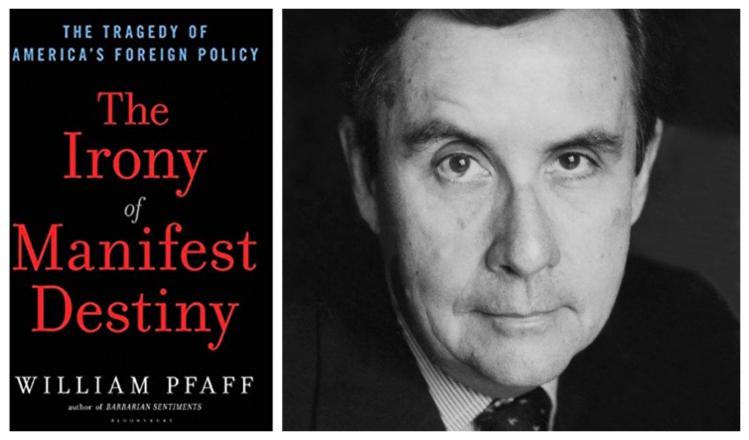

In his last book, The Irony of Manifest Destiny (2010), Pfaff linked the preceding decade’s war against Islamic radicalism to a long line of American exceptionalism—from the United States’ inexorable westward expansion to its emergence as a global superpower and Cold War crusader. This emphasis on the historic context for political and military conflicts was the great strength of his writing. Allusions to the fate of the Roman Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire abound. For most of the Cold War he wrote that Soviet Communism was a spent force, soon to be overwhelmed by nationalism and its own contradictions. In that respect he was correct. He also warned of American hubris and a potential day of reckoning—an imperial implosion—if the United States continued to overextend itself. Over the decades, there have been few to no takers for his policy prescriptions. And yet thus far, the United States has managed to hold on to its global preeminence. Time alone will tell if Pfaff’s warning of imperial overreach and collapse was prophetic.

Notably, Pfaff’s worries in “The Lay Intellectual” turned out to be unduly pessimistic. He filed his last column in April 2015, two weeks before his death. Written from his Parisian apartment, in a room with a view of the Eiffel Tower, Les Invalides, and Sacre Coeur, he addressed David Cameron’s decision to hold the Brexit referendum. Contrary to his fears, Pfaff was not in a trailer park in Arizona or in the Caribbean, nor was he propped up with a gin telling wide-eyed university students stories of the Cold War. He lived out his lay vocation, the life of the mind, right up to the end.

Pfaff’s service to democratic society brought countless readers the pleasure of a better understanding of international affairs. But despite his access to the highest levels of power, Pfaff left little to no mark on actual policy during a lifetime of writing. From the 1960s on, Pfaff kept on criticizing the Manichaeism, messianism, and utopianism that perennially marred American foreign policy. One of Pfaff’s major themes was the endurance of national character; yet when it came to his own country, he always hoped that he could help improve it, if ever so slightly. But the United States went on as before. Unheeded, though not unheard, in his own country, William Pfaff’s real legacy was not his influence but his example of intellectual integrity: he bore witness to another, better way.