After procrastinating for most of the summer, I finally got to the Norman Rockwell exhibit at the Mystic Museum of Art in Mystic, Connecticut. “Norman Rockwell’s Saturday Evening Post Covers: Tell Me a Story” was created by the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachuesetts. Rockwell (1894–1978) did a lot of covers for the Post—323, to be exact. He depicted a sleigh-full of rosy-cheeked Santas, dozens and dozens of baseball scenes featuring earnest young boys as well as grizzled old umpires, plenty of small-town New England street fronts and storefronts, and a number of courting scenes, or what Rockwell called “spooning.” Also, there are a surprising number of pirates and several kennels’ worth of dogs.

As the exhibit’s explanatory commentary reminds us, Rockwell’s work “celebrates the extraordinary of the commonplace.” Of course, he was famous for using neighbors from his small Vermont village and his subsequent home in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, as models for his paintings. I’ve lived for most of my life in New England, and I’m a pushover for Rockwell’s brilliantly drawn and painted “narratives.” Even his critics concede that he was a master draftsman. The drawings and paintings really do draw you imaginatively into the lives of the figures on the canvas, and often do so with a mischievous, if sometimes corny, sense of humor. Yes, his illustrations and paintings are celebrations of an idealized America, one mostly devoid of conflict or political turmoil. But ideals have their uses. It’s hard to make progress without them.

Naturally, I’m also curious about the history and content of all sorts of magazines, and I was keenly interested in reading as well as viewing the Post’s covers. I did not know, for example, that the Post, which was launched in 1916, had more than 2 million subscribers during the 1920s, a fact it boasted of on many of its covers. It ceased publication in 1967, a victim of television and the changing tastes of a more restless American public that had grown tired of the magazine’s staid and generally conservative fare.

The roster of writers featured on some of its early covers is impressive, including Ring Lardner, Sinclair Lewis, and Edith Wharton. By the middle of the 1920s, P. G. Wodehouse, J. P. Marquard, and F. Scott Fitzgerald are contributing. Fitzgerald appears in 1926, the year after the publication of The Great Gatsby. I was somewhat surprised to see that “The Memoirs of Benito Mussolini” ran for several issues in 1928, six years after he took power in Italy. (Then again, Mussolini had some surprising admirers.) A. Conan Doyle shows up in 1929, only to become Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in 1930.

Like the movies of the 1930s, the exhibit explains, Rockwell did not depict “the misery of the Depression.” Instead, in keeping with the Post’s conventional views, he focused on homespun domestic comedy. However, during World War II he contributed mightily to the wave of patriotism that swept the country with vivid “stories” of soldiers pensively heading to the frontline or somberly returning home. His version of “Rosie the Riveter,” the popular World War II image, shows a muscular young woman pausing for a sandwich at lunchtime, while still holding her pneumatic riveting gun across her lap in a gesture of determination and strength.

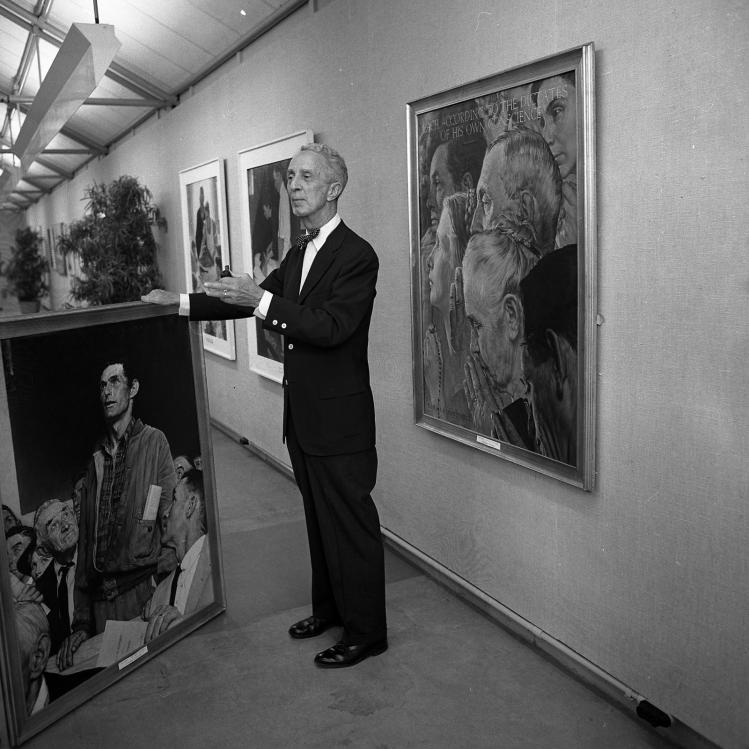

Rockwell’s most famous paintings were a 1943 series for the Post depicting what President Roosevelt had called the “Four Freedoms”: Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Worship, Freedom from Want, and Freedom from Fear. In the first painting, a modest working-class man rises to speak at a town meeting; in the second various religious worshippers are shown praying (one with a rosary); in the third a grandmother places a fat Thanksgiving turkey on the table; and in the fourth a couple tuck their two small children into bed for the night, while the father holds a newspaper whose headline reads “Bombings.” The U.S. Treasury Department soon used copies of these paintings to sell war bonds.

In the 1950s, Rockwell returned to more familiar subjects, although the Post also began asking him to do portraits of celebrities and presidential candidates. His last cover for the Post was in December 1963, when they reran the earlier portrait he had done of John F. Kennedy from the October 1960 issue during his campaign against Richard Nixon. “In Memoriam: A Senseless Tragedy” was the headline of the post-assassination cover. For someone my age—I was twelve when JFK was killed—the image is haunting. So was the headline from a 1957 cover: “How Will America Behave If H-Bombs Fall?”

One of the reasons Rockwell left the Post in 1963 and moved to Look was to tackle more controversial subjects, especially the civil-rights movement then convulsing the nation. In January of 1964 Look ran his painting “The Problem We All Live With,” which shows U.S. marshals escorting Ruby Bridges, a six-year-old Black girl, to school in New Orleans in 1960. A copy of the painting was in the exhibit in Mystic. Bridges marches bravely forward between four marshals, while an angry crowd out of view throws rotten fruit at them. Bridges went on to be a civil-rights activist and in 2011 President Barack Obama invited her to the White House where Rockwell’s painting was being displayed. “I think it is fair to say that if it hadn’t been for you guys, I might not be here and we wouldn’t be looking at this together,” Obama told her as they stood before the painting.

I left the exhibit thinking that an America closer to the ideals Rockwell illustrated—freer from want and fear, and freer from prejudice and intolerance—would be helpful these days.