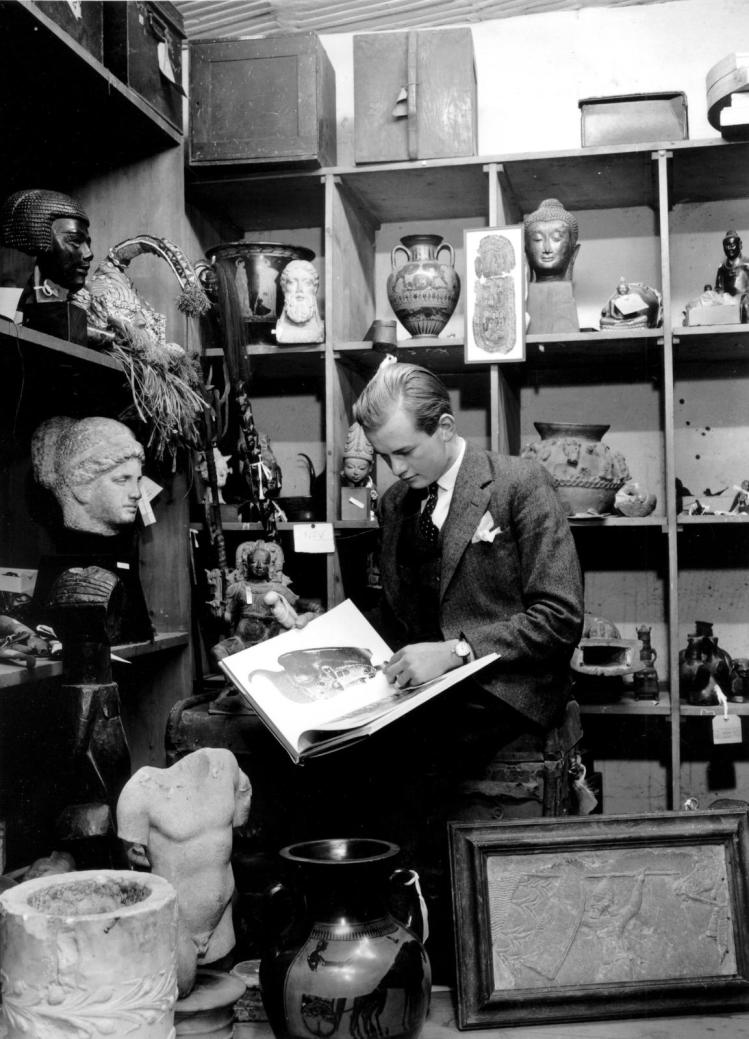

In the great swashbuckling English tradition, Bruce Chatwin liked to present his adventures as the products of impulse. At the age of twenty-six, already a director at Sotheby’s and in charge of the firm’s antiquities and Impressionism departments, he abandoned his art-world career to study archaeology. He left his studies in turn to become a writer and then, one day, as the story goes, disappeared from civilization altogether with only a telegram to his office at the Sunday Times: “Gone to Patagonia.” So began a literary career that would be the inspiration and the envy of a generation of British writers and dreamers—a T. E. Lawrence or Rudyard Kipling for the postcolonial era, dashing but humane, inspired but conflicted. “Nearly every writer of my generation in England has wanted, at some point, to be Bruce Chatwin,” wrote Andrew Harvey in the New York Times.

Chatwin’s great themes have been canonized, used to organize posthumous collections and trotted out on publication anniversaries: his passion for the remote and exotic, his compulsive storytelling that blends fiction and fact, his fascination with nomads and the peripatetic tradition, and his ambivalence about art and its capacity both to liberate and to obsess. We remember the self-creation myth that emphasizes Chatwin’s freedom: his capacity to move through the world without the bourgeois tether to home, his travels on foot through the remotest corners of Asia and Africa, his life with nomadic tribes.

But the opening pages of In Patagonia—the product of that first great defection and the book that propelled Chatwin to stardom—also tell a story of constraint and terror. When he was a small boy in England at the dawn of the Cold War, his teacher warned the children that the atomic bomb would “smother the world in an endless chain reaction.” The children understood, Chatwin recalls, that the bomb shelters where they practiced hiding would not save them. War would be in the north, so the Global South would be the safest place to flee to. Since islands were a trap, his best chance of survival, little Bruce concluded, would be at the end of the South American continent. Maybe he could survive in a timber-roofed hut in Patagonia.

As a boy, while he was imagining the end of the world through nuclear holocaust, Chatwin’s most beloved object was a prehistoric piece of skin that sat in his grandmother’s curio cabinet, sent to her as a souvenir by her seafaring cousin, Charlie Milward. The skin, Chatwin’s mother told him, belonged to a brontosaurus drowned in the Flood because the creature was too large to board Noah’s Ark. His grandmother’s promise to bequeath it to Bruce proved empty: when she died, his mother threw it away. A teacher admonishes Bruce that the skin could not have belonged to a brontosaurus; instead, it must have belonged to a mylodon, likely perished in the so-called “Mylodon Cave” in subantarctic Chile. This talismanic object becomes the beginning and the end of In Patagonia—and, in a way, of Chatwin’s short life.

In Patagonia documents Chatwin’s meandering journey through the southernmost region of Chile and Argentina. The narrative is composed of a long series of vignettes, mostly encounters with the miscellaneous outcasts and expatriates who have made their lives in that inhospitable landscape. These characters seem to live outside the flow of history. Some are stuck in the moment of a defining trauma—still in black, mourning the death of a husband, or still in a Germany on the brink of defeat, with a portrait of Hitler behind the dinner table. There is a manor house built to look identical to its owner’s Scottish homestead, a defunct seminary whose occupant holds forth on the archaeologically verifiable existence of unicorns, and an Indigenous community with only one surviving member. Chatwin’s narrative digresses into tales of Butch Cassidy’s mysterious disappearance into Patagonia and the British navy’s ill-fated expeditions to the region (here overlapping with David Grann’s bestselling The Wager, which sits beside In Patagonia in the region’s gift shops). The stories are adventurous and thrilling but also haunted by a deep human horror: the desire for discovery—for Chatwin, the essence of being alive—inevitably finds what already has been killed off.

Utz, Chatwin’s final novel, begins with the death of an eponymous protagonist whose desire, like Chatwin’s own, is first awakened by an object in his grandmother’s house—here, a harlequin figurine. When his grandmother dies, little Utz, crucially, inherits the treasure. He spends the rest of his life collecting porcelain figurines from the famous lost Meissen factory, embodying the myopia Chatwin saw and feared in the art world and in himself. As the Soviet Union collapses into violence and repression, Utz’s life in Prague is constantly threatened, yet he cannot bring himself to leave home if it means abandoning his collection—and so he is imprisoned in a gilt cage of his own construction. “Things,” Utz explains with devastating ambivalence, “are the changeless mirror in which we watch ourselves disintegrate.”

This conviction seems never to have been far from Chatwin’s consciousness. His first exotic trip—to Africa during his Sotheby’s days—was occasioned by the inexplicable loss of sight in one eye. Chatwin understood this to be psychosomatic and was sure it had been caused by staring at the dead objects that populated the collector’s world, a literal myopia. He told his boss at Sotheby’s that the optometrist had prescribed “long horizons”—to which his boss reportedly replied, “I’m sure there is something wrong with Bruce’s eyes, but I can’t see why he has to go to Africa.”

Utz’s harlequin is perhaps a variant of a real porcelain figurine that sat beside the mylodon skin in the curio cabinet of Chatwin’s grandmother. Werner Herzog’s 2019 film Nomad, about the director’s deep kinship with Chatwin, shows Herzog and Nicholas Shakespeare, Chatwin’s biographer, handling that very figurine—an old man with a walking stick and traveling cloak who stands above a description that reads, “I am starting for a long journey”—in the archive of their friend’s things at Oxford’s Bodleian Library. The adventures that Chatwin would embark upon in life, Shakespeare explains, were already determined by the contents of that cabinet: Chatwin would go searching for each object’s origin story.

The traveler figurine appears in On the Black Hill—a novel about Welsh farm life across the disruptions of the twentieth century—among the posthumous possessions of the protagonists’ grandfather. He is the book’s stand-in for Chatwin himself, the kind and gentle counterbalance to the twin boys’ brutal father. One day, when he knows death is near, the grandfather descends from his little attic room with his old fiddle in hand and stands out in the open air, playing and dancing to greet his end. It is one of Chatwin’s most tender and ecstatic scenes, one suffused with his unabashed desire to meet death in like manner.

Few writers have succeeded in commanding the formal range that Chatwin did. Each of his five extraordinary books—all written before the age of fifty—belongs to a different genre, even as their style and themes are all irreducibly his. Each book is an effort to understand people who find themselves at the end of a way of being, and each is, for Chatwin, deeply personal. Even his anti-colonialist historical novel of the slave trade, The Viceroy of Ouidah, is intertwined with its author’s mortality. While doing research for the book in Dahomey, Suriname, Chatwin was caught up in a coup, detained, and—as detailed in a 1984 essay he wrote for Granta—very nearly slated for execution as a presumed mercenary.

By the time Herzog was adapting The Viceroy of Ouidah for his film Cobra Verde, Chatwin’s mortality was again close, and this time inescapable. (According to Herzog, Chatwin had consented to Herzog’s buying the film rights only because David Bowie was about to buy them.) The filmmaker invited his friend onto location in Ghana, promising Chatwin—who was by then in a wheelchair, useless on the Ghanaian sands—a litter borne by four men so that he might travel like the real kings Herzog was filming. Invigorated by the shoot, Chatwin managed to walk on his own all during the two weeks of his visit. Footage for the film was the last thing Chatwin ever saw. Herzog had brought reels to his friend’s bedside and played them in the moments when Chatwin was lucid. Chatwin insisted that Herzog inherit his iconic leather rucksack, then asked him to leave so that he might die privately.

Herzog and Chatwin had first met in Australia when Chatwin was conducting research for The Songlines. The heavily autobiographical novel follows its narrator’s discovery of aboriginal “dreaming tracks” that run across the Australian Outback—paths mapped by a mysterious sung, mnemonic method of navigation that’s also a system of belief and of social organization. The narrator, Bruce, accompanies a group of white researchers and activists attempting to advocate for Indigenous communities and document the mystical topography that the national railroad’s development plans will destroy. This plot gives way to a fragmentary section drawn from Chatwin’s travel notebooks for a project he never finished, The Nomadic Alternative.

Chatwin was fascinated by nomadic tribes. He believed that man is fundamentally a peripatetic creature, that the proper end of life is to walk oneself to a happy death, and that religions in which the spirit travels to another realm after the body’s demise have merely displaced a journey proper to the world of the living. With his wife Elizabeth he kept a home in rural England, where he would return after his adventures. But soon he would develop the itch and be off again, wracked by what he called horreur du domicile.

Chatwin develops his theory of walking through the commonplace and anthropological entries of The Songlines, in the voice of a narrator about whose conclusions the historical Chatwin expressed doubt. This theory of walking is also a theory about the end of the world.

One Songlines journal entry recounts the author’s attending a lecture by the famous Hungarian writer Arthur Koestler during the height of the Cold War. According to Chatwin, Koestler argued that, due to “an inadequate co-ordination between two areas of the brain—the ‘rational’ neocortex and the ‘instinctual’ hypothalamus—Man had somehow acquired the ‘unique, murderous, delusional streak’ that propelled him, inevitably, to murder, to torture, and to war.” Koestler claims that “since Hiroshima, there had been a total transformation of the ‘structure of human consciousness’: in that, for the first time in history, Man had to contemplate the idea of his destruction as a species.” From his seat in the audience, Chatwin objects that, at the first millennium, “people all over Europe believed that a violent end of the world was imminent. How was the ‘structure of their consciousness’ any different from our own?” Koestler retorts, to the audience’s applause, “Because one was a fantasy and the H-Bomb is real.” Chatwin is indignant at the crudity of this distinction. There is a pathetic bravado in deciding that apocalypse—the great psychic, Biblical, geological, cosmic truth—depends on a recent technology. Was it the atom bomb that killed the brontosaurus?

Instead—in a Freudian, Jungian, slant-Christian mode—Chatwin’s narrator develops an idea. Contemplating the point at which early humans supplanted their predators at the top of the animal hierarchy, he wonders:

If, indeed, there was one big cat, or several, who preyed specifically on our hominid ancestors, the achievement of such research is to have reinstated a figure whose presence has grown dimmer and dimmer since the close of the Middle Ages: the Prince of Darkness in all his sinister magnificence. The jump in the evolutionary record suggests that, at a certain moment, man became able to overpower this primal predator. This was our great victory. Yet perhaps it had been a Pyrrhic victory: has not the whole of history been a search for lost monsters? A nostalgia for the Beast we have lost? We must be grateful to the Prince who bowed out gracefully. For the first weapon the world would have to wait until about 10,000 BC, when Cain crashed his hoe through his brother’s skull.

Why, in our primal myths and also in the social worlds we bring into being, is there a Destroyer, a violent, consuming Other? Why do we create—in our own minds from childhood, and then in an external reality we inflict upon others—forces that can become catastrophic? Perhaps the Fall was not quite the expulsion from the Garden but rather the attainment of supremacy. Perhaps that is man’s origin story, the one that lies in the depths of his psyche and that he is compelled to repeat—for Chatwin’s century, in the creation of the atomic bomb, and for ours, in the environmental desecration of the planet.

“My whole life,” Chatwin writes in an essay about possibly having seen the tracks of a Yeti—another monster of our collective unconscious—“has been a search for the miraculous: yet at the first faint flavor of the uncanny, I tend to turn rational and scientific.” Chatwin knows how limited our modern vision is, but he does not believe in an Eden of the noble savage to which we could return. Like so many travelers and dreamers, he goes searching for an antediluvian myth—a land before civilization, before his brontosaurus drowned—but as with other great romantics, the closer he gets to such a myth, the more distant it proves. It is this recognition that saves Chatwin’s fascination with nomadic tribes from becoming a colonialist idealization: he understands that their lives are marginal, that many of the nomads themselves are ambivalent about their relationship to modernity, and that many would prefer a house with a shower.

Even as a boy, Chatwin was dreaming not of the pristine wild but of salvaging something from the wreckage of modernity. He hoped he might be safe in a timber-roofed hut in Patagonia if the rest of the world already had been bombed beyond recognition. But the bombs did not actually need to fall for Patagonia to call to Chatwin: the possibility of destruction had already been established in the collective imagination. Even if his brontosaurus hadn’t perished in the Flood, the mylodons had gone extinct.

Chatwin was forty-nine when he died of HIV-related complications in 1989. In his final BBC interview, he looks like the “dead man walking” he describes in The Songlines, his bright blue eyes barely contained within his emaciated skull. Chatwin gave various accounts of his illness to friends: he had eaten a rotten thousand-year-old egg; he had contracted a disease from rat feces; he had been infected by a rare fungus in China never before seen in Europeans, one that had killed “10 Chinese peasants...a few Thais and a killer whale cast up on the shores of Arabia.”

He was a magnetic presence. In Herzog’s film, Chatwin’s widow Elizabeth describes, without resentment, her husband’s bringing home “charming” men to stay the weekend. Edmund White, in his 2011 memoir, recalls being seduced by Chatwin in an elevator. Herzog himself speaks on camera of the effort needed to maintain a certain remove from his friend. Chatwin emanated and elicited desire with the intensity of a collapsing star.

When his bisexuality and the real nature of his illness were made public following his death, the man and his work suffered vicious condemnation. For decades thereafter, literary critics and journalists excoriated Chatwin as a liar, a huckster, and a pervert, tying the fabricated etiologies of his illness to the dubious facticity of his writing. Gay activists, too, criticized him for failing to lend visibility to the AIDS crisis when he could have been the first British celebrity to battle the disease publicly.

Friends of Chatwin’s have since endeavored to reframe his alleged duplicity in literary terms. Salman Rushdie devotes a chapter of Imaginary Homelands to the task. Shakespeare says Chatwin modified fact in order to render it more true—not “a half-truth” but “a truth-and-a-half.” Herzog says Chatwin understood history itself as “aspiring to the symmetry of myth.”

I, too, have been tempted to find some element of conscious myth-making in Chatwin’s accounts of his own demise. But the fungal infection from which he finally died in 1986 was not yet associated with AIDS and had in fact been documented only in South Asia. An English friend and scholar of the AIDS crisis gently reminded me that, given the level of confusion that accompanied having HIV in the eighties, any account of that illness would necessarily have been partly imagined.

“Apocalypse,” etymologically, connotes an unveiling, a revelation at the end of things. In the final scene of The Songlines, the narrator follows three Aboriginal elders to the place where they have returned to die, which is where they were conceived. The three men lie on hospital bedsteads, greeting death with joyful and enigmatic smiles, having walked their way to a peaceful death, as Chatwin hoped to do. There is peace and there is pleasure, but there is no answer: only the symbol of their smiles beneath the ghost gum trees. What’s revealed when death finally arrives—in all Chatwin’s books, and in his own story—is an enigma. He was one of the only subjects Robert Mapplethorpe photographed clothed.

I visited the Mylodon Cave this past spring, on the first day of a trip to Patagonia I’d dreamed of for a decade. The cave is an improbable feature in a massive head of stone facing the Last Hope Sound, where nineteenth-century explorers discovered the remains of the now-extinct giant sloth-like creature from fourteen thousand years ago, preserved in the cold.

I came to the cave late in the day, shortly before the park closed. I had the site nearly to myself. As I followed the marked-off track into and around the cave, I suddenly found myself in tears, overwhelmed by the feeling that I existed in deep time—in a temporality in which eras were stacked on top of one another as sedimentary layers. Only the top layer of the cave floor has been excavated or analyzed; a deeper layer, likely filled with more extinct animal fossils and possibly with early human remains, remains untouched.

I found there was no cell reception at the site, and I hadn’t arranged for a taxi to take me the twenty-five kilometers back to town. When I managed to communicate my predicament—mostly through ludicrous miming—to the jovial park ranger manning the site’s welcome kiosk, he offered to give me a ride back with him at closing time. I had an hour, then, to walk the hills above the cave, to stand on the lookout points over the sound. I tried to see south, to Tierra del Fuego, where early the next morning we would be beginning our trek among the vertiginous stone spires of Torres del Paine. I was alone on the slopes, and the notorious Patagonian winds were picking up. The large birds of prey circled a little too near for comfort.