I learned of Gene Hackman’s recent death on the New YorkTimes website, which ran a 1973 photo of him gazing into the camera with a characteristic look of probing, wary intelligence. My wife Molly walked by, saw the headline, and uttered a yelp of distress, because Gene Hackman is her favorite actor ever, bar none.

It has always been an enjoyable joke in our marriage—the crush Molly had on Hackman. The joke was not her passion for a movie star, but rather her insistence that Hackman was the sexiest man on the screen, and the most handsome. Handsome? Gene Hackman? I subjected her to no end of kidding about that, kidding that was a bit uneasy on my part (Wait, my wife thinks a balding portly guy is handsome, and she thinks I’m handsome, so…). What Molly was responding to, of course, was Hackman’s charisma—his signature combination of intensity and intelligence, an ability to convey layers of awareness and experience that gave his portrayals remarkable depth. Hackman was not movie-star handsome, but his human magnetism was off the charts.

And then there was his voice. Sandpapery, resonant but ever so slightly nasal, it was a hollerin’ kind of voice, betraying no particular regional origin (the actor grew up in California and the Midwest). Yet it was also welcoming and warm. Hackman did a fair number of commercial voiceovers, and you always instantly knew who it was, that calm voice genially flacking for OppenheimerFunds, Lowe’s, and United Airlines. Fly the friendly skies! In fact, it’s surprising that Hackman, an avid pilot in real life, never played an airline pilot. Can’t you just see him in a pilot’s uniform? And wouldn’t he be the guy you’d want at the controls if your plane got in trouble? A later generation of leading men seemed intent on remaining eternally boyish, the Brad Pitts and Tom Cruises and Leonardo DiCaprios. Hackman was the opposite: he sprang into his career already a full-grown man, his characters brimming with competence. In portraying them, he had a matchless ability to project an impression of real life. “Even the way he chews gum!” my wife enthused as we watched one of his movies. Whatever he did, whatever he said, you just believed him.

The other marquee male actors of his generation—De Niro, Pacino, Hoffman—relied on over-the-top performances and at times risked becoming parodies of themselves. (After a certain point in his career, I found it impossible to watch Dustin Hoffman without thinking, “I’m watching Dustin Hoffman acting.”) Hackman played it cool. He could completely take over a scene without setting off any acting fireworks. One of my favorite Hackman scenes occurs halfway through Scarecrow, a 1973 road/buddy movie in which he co-stars with an achingly young Al Pacino. It’s a dinner-table scene in which Hackman’s character, a roguish and bespectacled ex-con named Max, lays out his grandiose vision of opening a car wash to his sister, his sister’s best friend, and Pacino. Chugging beer, gorging on chicken from Colonel Sanders, and fielding the amorous advances of his sister’s friend all at once, Max never breaks from his drunken monologue, rapturously evoking his car wash and its pricey appurtenances (“The finest Mediterranean sponges—three hundred bucks! Pure hair hand brushes—that’s two hundred smackers, all right? Two hundred smackers!”). It’s a mesmerizing performance.

The morning his death was announced, The Today Show’s pop-culture guy, Carson Daly, commented that “Hackman never made a bad movie.” That’s a fatuous remark; anyone who does eighty movies ends up in plenty of bad ones, and Hackman appeared in any number of films that he himself dismissed as “money jobs,” as Ben Stiller amusingly recounted after his death. What Daly perhaps meant to say was that Hackman could make even a lousy movie worth watching; for a viewer, seeing him in a bad film was like arriving at a crowded party where you don’t want to be, and then spotting the one crucial person you know you can have a fascinating conversation with. Phew, you think, at least he’s here—thank God!

In bad movies Hackman saved many a viewer from tedium, even as he showcased a type and quality of acting jarringly at odds with the mediocrity around him. In his early film First to Fight, Hackman (himself a Marine Corps vet) is a World War II gunnery sergeant in a platoon whose lieutenant, played by Chad Everett, experiences incapacitating battle fear. Bookended by voiceover narration lauding the heroism of American soldiers and the Marines in particular, the movie was released in 1967, but could have been made fifteen years earlier. Amid its pro forma patriotism and wooden conventionality, Hackman seems to inhabit a completely different dimension of acting. Infusing his role with a vibrant directness, he’s like someone beamed in from the world of Scorsese and Coppola and Altman, and his presence seems startlingly anachronistic, a harbinger of the glorious era of American cinema to come—an era in which he would figure so prominently.

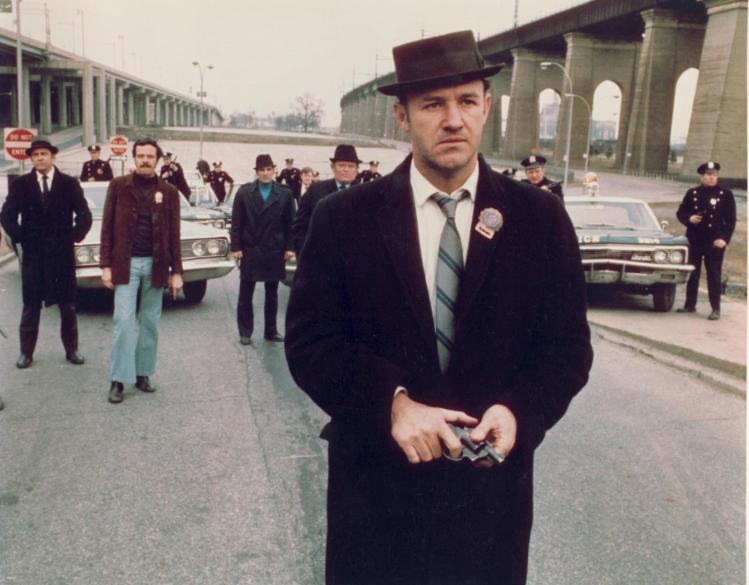

Hackman’s filmography is colossal, and it’s chastening to realize just how few of his movies one has seen (fewer than half, in my case, which is still thirty-eight films!). Culling my favorites, I find myself thinking less about the movies themselves than about the roles Hackman played, and the qualities they drew forth from him. Clyde Barrow’s brother in Bonnie and Clyde—good-natured, with a doglike loyalty; Popeye Doyle in The French Connection—reckless and relentless; surveillance expert Harry Caul in The Conversation—introverted, haunted, and intensely private; the sheriff in Unforgiven—gleefully sadistic; the submarine commander in Crimson Tide—arrogant and bullheaded; a senior law partner in The Firm—cynical and calculating; a chain-smoking tobacco tycoon in Heartbreakers—foolish, a dupe, a mark; the eponymous patriarch in The Royal Tenenbaums—rakishly eccentric. Hackman also acted in tender family dramas like I Never Sang for My Father, playing a widowed college professor overshadowed by a domineering father, or Twice in a Lifetime, playing a Seattle steelworker turning fifty and mired in a dead marriage who undertakes an affair (with Ann-Margret) and decides to leave his family, sparking enraged recrimination from his grown daughter (played with hot fury by Amy Madigan).

The perplexed and poignant men in these family dramas were outlier roles for him. The classic Hackman character possessed a volatile quality, an ability to shift rapidly from one emotional state to another, that often betrayed a combustible potential for violence. That potential surfaced in places you didn’t expect it. Max, the eccentric drifter he plays in Scarecrow, is fundamentally a likable rogue. Yet we know he served time for assault, and his tendency to explode when he feels insulted keeps us worried, wondering just when and how the amiable road hijinks with Pacino’s character are going to be derailed by an outburst. This worried expectation gives rise to what is perhaps the single funniest moment in Hackman’s long career. It occurs in a crowded bar where, taking a cue from the impish clowning of Pacino’s character, Max forcibly curbs his own belligerent behavior. He averts a nasty brawl that he was about to launch—and, instead, as the jukebox plays “The Stripper,” performs an impromptu striptease as the whole bar erupts in hilarity.

The ability to hold opposites together, to be thinking one thing and showing another, made Hackman the ultimate poker player of actors. Take by comparison another tough-guy actor of his generation, Clint Eastwood. Eastwood trademarked a facial expression that signaled impending violent harm. Someone says or does something to provoke an Eastwood character, and here comes that Dirty Harry look. Eyes narrowed, mouth a flat line, that seething look conveys icy anger and also a note of incredulity—you’re gonna say that to me? It is the visible fizzing of the fuse on a bundle of dynamite. Not Hackman. Confronted with a threat in the form of a male antagonist, the Hackman character just…smiles. Has any actor ever put more into a smile? Contempt, restrained anger, a menacing readiness for violence; but also pleasure. His character is prepared to commit mayhem, but he is also withholding it, and enjoying both the withholding and the prospect of gratification—a cruel cat toying with the helpless mouse.

This faintly obscene pleasure informed the power characters Hackman portrayed so enjoyably in the latter half of his career. In Runaway Jury, he plays a Machiavellian jury consultant helping defend a gun manufacturer in a civil lawsuit led by a liberal-minded litigator (Dustin Hoffman). Stymied by setbacks in the courtroom, and with millions at stake, Hackman’s character undertakes to flat-out buy the jury. The crassly corrupt move outrages Hoffman’s character, who righteously upbraids Hackman in a face-to-face encounter. Summoning maximum eloquence, and appealing to an implicit shared humanity, Hoffman predicts an eventual reckoning for Hackman’s character, conjuring a future moment when his life is winding down and all he’ll be left with is the knowledge and memory of how many lives he helped destroy. “You may be right,” Hackman says, when the soliloquy is over. “The thing is, I don’t give a shit. What’s more, I never have.” And then he smiles, ever so warmly. That warmth is the killer. Again and again, it helped Hackman endow humdrum corporate and political malfeasance with a Shakespearean force of villainy, bringing a touch of nihilism to otherwise lightweight movies.

Interviewed by Terry Gross on Fresh Air in 1999, Hackman offered a methodical explanation of how an actor inhabits characters who are, in important ways, very different from himself. You find an area of overlap, he said, then isolate the shared trait, ground your performance in it, and build upward from there. Well, Gross responded, what if that character is brutal or even sadistic, like the sheriff Hackman portrayed in Unforgiven? How do you manage to become a sadist? Hackman thought about it. “I find something in myself that is not very attractive,” he said, and then he paused. “If you search hard enough, you can find something.”

Hackman always knew what to find and how to use it. In The Firm, a 1993 legal thriller directed by Sydney Pollack, he plays Avery Tolar, a senior partner in a glossy and secretive Memphis law firm whose real work is money laundering for unsavory clients, including mobsters. Complicating matters is Mitch McDeere (Tom Cruise), a new hire at the firm, fresh from law school, whose initial euphoria at his lavish job offer quickly gives way to dark suspicion about the firm’s true nature. As an antagonist for Hackman’s character, Mitch is much younger and more naïvely idealistic than Dustin Hoffman’s weathered lawyer in Runaway Jury, and we sense that Tolar may see in him a younger, uncorrupted version of himself. So even as Hackman conveys with typical relish his easy, comfortable possession of power, even as we note that he is cynical, scheming, charming, and corrupt, we remain unsure: How corrupt is he exactly? Is there, trapped within him somewhere, a good man trying to get out? Or…not? Dramatically and emotionally, the film turns on the question of Tolar’s ultimate intentions. Will he thwart Mitch’s effort to dig into the firm’s illicit business, or will he jump ship and help?

It is the kind of question Gene Hackman exploited so productively in his long and glorious career. Holding his cards close to his vest, flashing that ambiguous and sometimes scary smile, he did a crucial thing better than any actor of his era: he kept us wondering.