“A woman’s life is a blood sacrifice,” Sr. Lucy tells Sally, the teenager shadowing her as she goes about her work in Alice McDermott’s new novel The Ninth Hour. It’s not a complaint: the suffering of women is a doctrinal given, “our inheritance from Eve.” But a nursing sister needs more than doctrine to do good, and Sr. Lucy also wants Sally to see how “poverty and men made a bad situation—to be born female—worse still.”

The Ninth Hour is set mainly in an Irish Catholic neighborhood of early-twentieth-century Brooklyn. It opens with the suicide of an immigrant named Jim, but the focus is on Annie, the pregnant wife he leaves behind, and the community of sisters who become a family for her and Sally, the daughter she gives birth to. That community—the Little Nursing Sisters of the Sick Poor, Congregation of Mary before the Cross—finds work for Annie in the convent laundry, where Sally grows up as a favorite of the nuns.

McDermott shifts perspectives over the course of the novel to show us the events in Annie’s life through the eyes of a variety of women, including several of the nursing sisters. All of them are, in their own ways, standing before the cross, bearing witness to suffering, accepting it, confronting it, and feeling powerless to stop it. Sr. St. Saviour, the first at Annie’s side after Jim’s death, considers the despair that must have driven him and is convinced “God Himself was helpless against it.” Assessing the impossible situation in which the family has been left—suicide placing Jim outside the church’s comfort, and his wife abandoned with no support—she recalls an instruction she had been given long ago at a sickbed: “There’s nothing to be done,” an older nun had told her. “Do what you can.”

The lives of Sr. St. Saviour and all the sisters are shaped by the routines and strictures of the church, including the liturgy of the hours to which the novel’s title alludes. They accept those limits, even embrace them. But each woman has her own way of making sense of the conflict between the God of love she worships and the unfairness she sees in the world. Sr. St. Saviour prides herself on circumventing the many “rules and regulations” that “complicate the lives of women: Catholic women in particular and poor women in general.” Arranging for Jim to be buried in his Catholic cemetery plot, cause of death notwithstanding, is an act of mercy she feels determined to carry out. “Hold it against the good I’ve done,” she prays. (“You can’t pull the wool over God’s eyes,” mutters grim Sr. Lucy.)

Jim and Annie’s grandchildren are the novel’s narrators, representatives of the good the sisters did in keeping Annie and Sally going, though we never learn their names or how many of them there are. They resurface here and there, identifying themselves only as “we,” interjecting details from far in the future, revealing the ripple effects of Jim’s death, Sally’s birth, and everything after. They marvel, not without condescension, at “how much went unspoken in those days”—in particular, at undiagnosed cases of depression and mental illness, which they have learned to recognize in their mother’s “midlife melancholy”—and also at “how much they believed was at stake.”

The Ninth Hour, like all of McDermott’s writing, is an unalloyed pleasure to read. The story is dramatic and satisfying; the writing is rich with symbolism but never simplistic or pat. The world she creates is no soft-focus period setting; you can feel it and see it as the characters do, not quaint and foreign but familiar and lived-in. You can smell the soap and dampness of the convent’s basement laundry, a kind of purgatory where dirt is washed clean, “fresh linens folded, stains gone, tears mended.” Outside it is “the wider world,” all that the sisters left behind when they took their vows—“the world above their heads,” where the sisters minister and to which Annie looks for escape from her cramped circumstances. There are other recurring images, too, small details that echo with meaning: the stinging scent of ammonia, or the sight of dirty fingernails, or the way multiple characters express dismay with an un-ironic “Glory be to God.”

In the pre-Pill days when most of the action takes place, the sisters talk euphemistically about “the duties of married life” and the various bad situations in which married women find themselves as a result. “Some of them suffer for it. Babies coming every year,” Sr. Lucy tells Sally. “Others impose the suffering on their men.” Sex is seen always as a burden to be tolerated or a sorrow to be borne—our inheritance from Eve. There is no room in this worldview for Annie’s discovery that sex can be a refuge from sorrow, a release from her purgatory. Her violation of the rules that govern the lives of women is the crisis that throws the plot into high gear and tests what the sisters believe about God and sin and love and fairness.

The rigidity of the Catholic worldview in that place and time is a given, not questioned or rebelled against but accepted as the shape of things. Annie’s friend Mrs. Tierney, a mother of six, is grateful for “the order and the certainty the Church gave her life, arranging the seasons for her, the weeks and the days, guiding her philosophies and her sorrows” and “order[ing] her disorderly children.” What seems to interest McDermott most is the ways her characters maneuver within that framework, making room for mercy and comfort where they can. Sr. Jeanne, a young nun when the story begins and one of the novel’s most compelling characters, grounds her own goodness in a firm belief in God’s fundamental fairness, and cannot find hope for a man who would take his own life: “There was the logic of redemption, all undone.” All her life she clings to an image of God as fair in a world that manifestly is not, even when her own heart pulls her in another direction.

Annie, meanwhile, “never blamed the church” for casting Jim out of hallowed ground. “He’d murdered himself and murdered something in her as well. Who could argue for leniency? Who could expect absolution?” She knows as well as anyone how poverty and men can make demands on a woman’s life. Still, she names her child after Sr. St. Saviour, the nun who refused to accept the verdict pronounced against her late husband, who sought wiggle room in the church’s rulebook, whose heart was “mad for mercy.”

The stories told in The Ninth Hour don’t wrap up neatly or teach easy lessons. The grandchildren sharing those stories are a reminder that human lives don’t really wrap up at all—whatever you believe or disbelieve about the promise of eternal life, our legacy on earth outlives us. We fade into history, like Annie and Sally and the sisters, and the things that motivate us may come to look, at a safe remove, like “delusion and superstition.” But if we could see it up close, we might be inspired to witness how people in hopeless situations—women, especially—find a way to do what they can.

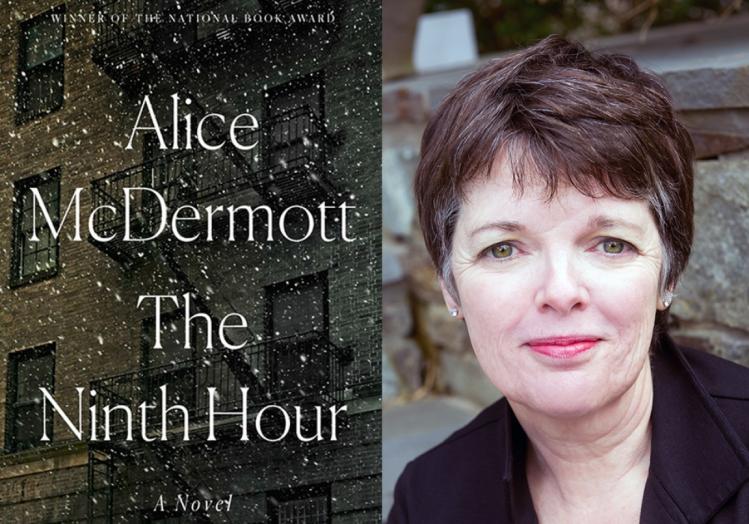

The Ninth Hour

Alice McDermott

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $26, 256 pp.