In addition to nineteen novels, British writer Tim Parks is the author of several books of nonfiction and numerous critical essays. A resident of Italy since 1981, he has also translated classics of Italian literature, including works by Niccolò Machiavelli, Giacomo Leopardi, Cesare Pavese, and Italo Calvino. Most recently, he translated poet and filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini’s “scandalous” and notoriously difficult novel Boys Alive (1955), published last fall by New York Review Books. He spoke about it via video conference with Commonweal associate editor Griffin Oleynick. Their conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

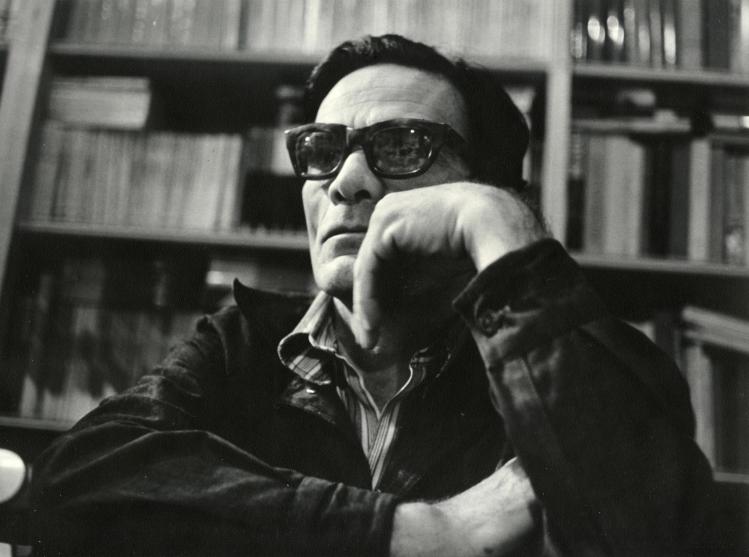

Griffin Oleynick: Pier Paolo Pasolini (1922–1975) is enjoying a resurgence in the United States. There’s the recent biopic by Abel Ferrara, starring Willem Dafoe. Besides Boys Alive, new translations of his novel Teorema and his critical collection Heretical Empiricism were also published in 2023. Could you give us a sense of Pasolini’s life? Who was he as an artist and public intellectual?

Tim Parks: Pasolini was a towering figure in Italy, and in many ways still is. When I speak to Italians who lived through the sixties and seventies, they say he was the one author who really made them sit up and listen whenever one of his pieces was published, or whenever one of his films came out in theaters.

Pasolini was born in Bologna in 1922, during Fascism. Unlike most Italians, he moved around a lot as a child (his father was a military officer, his mother a schoolteacher). He didn’t have a home city, or a home dialect, which is very important for Italians. During the Second World War, he moved with his mother to a small rural village near Udine, in the northeast, where he studied literature and wrote poetry in the Friulian dialect. He was drafted in 1943, before the armistice. But he managed to escape action, living incognito and working as a teacher.

It was then that Pasolini also realized he was gay. He’d fallen in love with one of his students, and came out publicly, with disastrous results. Just after the war ended, he was accused of molesting three adolescents. There was a court case. He was immediately expelled from Italy’s Communist Party and fired from his teaching job. Neither of the major orthodoxies of the time, Catholicism or Communism, would accept him. And Pasolini’s private world at the time was quite violent: his younger brother, who’d fought with the partisan guerillas during the war, had been killed. His father returned home from the war with a lot of anger. So Pasolini and his mother escaped to Rome in 1952.

Pasolini arrived in the capital as an outcast, thinking that all avenues of a conventional career in culture were closed to him. He’d been canceled, as we’d say now. He had never been to Rome, and it proved immensely stimulating. There, Pasolini discovered the gritty suburbs, where he was forced to live since he had no money. He also discovered the Roman dialect—aggressive, violent, full of earthy humor. And he fell in love with all the young, working-class boys and their chaotic energy, and with the idea that there could be a life outside the bourgeoisie. That formative moment is absolutely crucial for understanding Pasolini: his enemy is the piccola borghesia, small-minded middle-class people whom he attacked—in the press, in his films—for the rest of his life.

GO: That “peripheral” Roman world, especially its idiosyncratic language, is central to Boys Alive. Could you talk about how the book unfolds?

TP: Correct. There’s another strange thing about Pasolini: generally, when Italians move from place to place within Italy, they don’t learn the local dialect. Instead, they use standard Italian. But Pasolini threw himself into it, learning Roman dialect and using it to write short stories about the young men he was meeting. He found a young publisher, Livio Garzanti, who was willing to take a risk and, after heavy censorship, he strung the episodes together into what eventually became Boys Alive.

The book’s action takes place over a period of seven or eight years, from when the boys—there’s no single protagonist, really—are adolescents until they’re around twenty. All the episodes, which are often quite long, are set during the summer, during hot days and nights that seem to go on forever. They begin innocuously enough, with petty theft or a visit to a brothel, but then intensify in unpredictable, often violent ways.

Pasolini gives us a lot of life and intensity, but he never offers any moral take on the situation. This is in sharp contrast with neorealism, the dominant artistic mode in postwar Italy. Instead of critiquing the Italian state and deploring Italy’s poverty and social degradation, Pasolini actually seems to have a kind of enthusiasm for these wild boys.

The original Italian title, Ragazzi di vita, literally “boys of life,” is ambiguous. Most immediately, the term means boys who are living by expedience—that is, stealing, gambling, male prostitution. That strand is certainly there, and other translations have rendered them “hustlers.” But the idiomatic expression in the original title also invites a question: Is the book just about male prostitution, stealing, and so forth? Or is it also about kids who are immersed in life?

More importantly, what is Pasolini’s position with regard to these boys? (We know that he visited male prostitutes right to the end of his life—in fact, he was killed by one of them on a beach in Ostia in 1975.) In one sense, here’s Pasolini, a writer of immense talent, celebrating a form of “low” life that was a smack in the face for his middle-class readers. But in another, here he is placing a group considered beyond the pale of respectability at the very center of literary attention, giving them dignity. And he does so against the rigid legalism and moral rules of the bourgeoisie.

Pasolini believed in the importance of being yourself, which, as he once put it, means being unrecognizable, inasmuch as a person changes from day to day. That’s a difficult position to hold, but Pasolini was a difficult, contradictory person. He reveled in the interplay of clashing viewpoints.

GO: There is a certain tendency to sanitize and reduce Pasolini—many on the Left claim him as a kind of hero, others (some Catholics, for instance) claim him as a mystic. I think of him as an iconoclast. Do you agree?

TP: I’m not so sure. For one thing, Pasolini clearly loved images. He made strongly symbolic movies, about the gospels, ancient myth, and medieval literature. I don’t think he was so much against the icon or the image as such, as against the rigid ideologies that sustain it. Pasolini wasn’t somebody pulling down statues, as it were; instead, he was constantly trying to expose the small-mindedness of public discourse, of any system of thought that arrogated to itself the right to lay down rules about how other people should behave.

I suppose the nearest you could get to Pasolini’s “ethos” is a kind of vitalism. Pasolini was intensely attracted to life, and especially to danger. It’s as if he has to go and touch danger in order to feel alive. He has some grotesque descriptions of sex with male prostitutes on the beach in the late posthumous novel Petrolio: “Every night I risk getting killed,” he writes. “One of these nights I won’t come back.” As the novelist Alberto Moravia informs us, Pasolini really did engage in this kind of behavior compulsively, as if he had a kind of physiological need for it.

It’s rare for a person to be as talented and as lucid as Pasolini was. But people like him are incredibly useful for a society, even if they’re not guiding it, because they’re constantly provoking us to examine our own narrow-mindedness. For example, in the sixties, Pasolini made an absolute gem of a film, a little documentary called Comizi d’amore (“Love Meetings”). In it, he simply travels around Italy and talks to young people about sex. It’s a fantastic piece of work: not only does Pasolini get their opinions, but he then confronts them with how narrow and circumscribed some of their opinions are. Today, the film wouldn’t be radical; we’ve traveled a long way since then. But here, Pasolini is something more than a contrarian who just takes the opposing side. He foresees the whole trajectory of a culture of political correctness that would go on to become, at least at the level of speech, just as censorious and repressive as Fascism had been.

GO: You’ve told us what Pasolini is against, and what kind of life he’s attracted to. The problem is that Pasolini seems to lack a program. What does he want? What would he like to see?

TP: It’s true that Pasolini is more comfortable criticizing than proposing. And he doesn’t go into politics officially. It seems to me that insofar as Pasolini wants anything, he wants people to be honest—that is, he wants people to feel free to actually say what they think. If you think about it, can you imagine anything further away from the reality we live in today?

In Pasolini’s allegorical films, there’s always a character, one who usually appears to be an idiot or a “holy fool,” that just comes out and says what he thinks. That’s not by chance. Pasolini remained intensely attracted to religious art throughout his life. Remember that his 1964 film The Gospel According to Matthew is on the Vatican’s list of the greatest films of all time. We can even say that there’s a kind of sacredness to Pasolini’s art: as you move toward life and, because of its intensity, death, you enter into an enchanted, sacred space that gives life meaning—and without which life has no meaning.

Pasolini clearly wasn’t on board with any major religion and famously declared himself an atheist. But he had an immediate affinity with the extremes of religious experience: things like the Crucifixion or visions of the Virgin Mary. Pasolini’s approach to these subjects is interesting because he has an enormous respect for the emotions involved, even if he doesn’t share the metaphysics or beliefs that sustain Christianity. He loathed the institutional side of religion, how figures in power use rules and dogma to coerce others. He wants to be back with the revelation and the miracles, so to speak, not with St. Paul figuring out how the Church can get through the next five centuries.

GO: Pasolini’s spiritual homelessness seems to mirror the lack of a linguistic and cultural home that you mentioned earlier. Did you pick up on that as you were translating Boys Alive? What guided your rendering of Pasolini’s use of Roman dialect into English?

TP: Roman dialect is wild and intense, and Pasolini didn’t know it perfectly. He was also fond of literary allusions, which he folds in at the edges. Translating him was challenging, not least because it’s the Roman dialect of 1950, not now. His publishers had asked him to tone it down, but he insisted on keeping it because, for Pasolini, dialect is closely attached to life—and that includes all kinds of complicated hand gestures. Even when the boys stick their hands in their pockets, that means something.

A translator has to understand the difference between a problem and an impossibility. A problem can be solved; an impossibility can’t be, and the trick is to render things in a way that won’t make the book even worse. For example, William Weaver’s translation of Pasolini’s Una vita violenta (A Violent Life) puts dialect in the language of the Bronx. With respect, that’s a huge mistake, because dialect is closely tied to geography. Pasolini’s action isn’t set in New York; every page of Boys Alive is packed with very specific Roman place names. It’s as if he’s saying this is the kind of story that could only happen in Rome, and only in those years.

Translation, in this sense, is a loss—a huge one, almost as if it’s not the same book. Roman dialect has a very special position in Italian life and culture: Italian comedies and crime movies are often in Roman dialect. But an English reader is not Italian, and that lost context simply can’t be recuperated. So I used English that was very energetic and aggressive, but not geographically located—not particularly American, not particularly British, or any other place.

Even more difficult to translate are Pasolini’s long, lyrical descriptive passages of the Roman cityscape, where dialect words and phrases blend with standard Italian in loosely syntactic sentences. It’s hard to make them work in English, to give them the same impressionistic fluency. Pasolini is being very deliberate here: it’s as if the city, the time, the weather, the summer, the heat, and the boys are all one thing. The boys’ behavior, the names of streets, the flickering of a welding machine in a factory—all of it is tensely wired together. It’s one of the most difficult things I’ve ever translated.

But again, that difficulty—that’s Pasolini, and that’s why he’s worth reading. Books are no longer at the center of culture as they were back when Pasolini was writing. Maybe that’s something to fear, maybe it isn’t. Pasolini was attracted to fear, but he also wanted to overcome it. I don’t know whether we should praise or criticize Pasolini; it’s not clear to me that he could have lived any other way. His insight was that fear, especially bourgeois fear like our worries about property and social status and material security, is what gets in the way of living. Fear is deadly: it prevents us from engaging with life.