Those individuals with the most say over what happens in American classrooms are often several decades and pay grades removed from them. Some, like the philanthropist Bill Gates and College Board president David Coleman, have never taught in a K-12 school at all. This fact has not hindered them from drastically altering the landscape of the American classroom in recent years. Thanks to Gates’s $200 million push for the Common Core and Coleman’s reengineering of the SAT, public education has grown increasingly data-driven. Instruction focuses on analytical skills and points to measurable outcomes and standards, and more and more schoolwork occurs on computers and other electronic devices. But who reports what these changes actually look like from the ground?

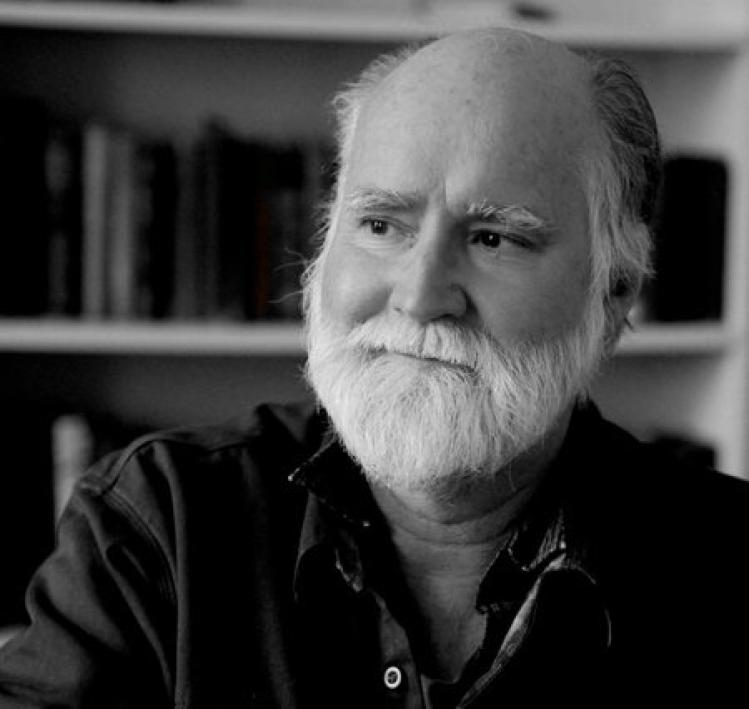

Enter Nicholson Baker, the award-winning novelist whose trademark is his attention to the quotidian: his work includes the steamy Vox, which consists entirely of dialogue on a phone-sex line, and Mezzanine, which occurs entirely during an escalator ride. In many ways he is the ideal writer to chronicle the minutiae of a modern school day. Spurred by a desire “to know what life in classrooms was really like,” he spends twenty-eight days as a substitute teacher in a public school district near his home in Maine, and records what he observes.

The result is Substitute: Going to School with a Thousand Kids, by far the most accurate portrayal to date of the modern American classroom. Teachers will instantly recognize the fragmented tedium Baker depicts—P.A. announcements, online learning games, worksheets, PowerPoint presentations—and the often heroic effort of students and teachers to carry on in spite of it. Baker’s painstaking attention to detail means that Substitute’s 700-plus pages are difficult to get through, but this is a necessary price to pay for a book that shows how the sausage is made.

A teacher myself, I came to this book armed with a major objection: Baker is a substitute teacher, not a full-time one. The students in his care do lots of busy work, but that’s what teachers assign when they write “sub” plans. By the very nature of his position he shouldn’t be able to see what really happens in a classroom. The recent direction of our educational system, however, has complicated this assumption, for in the classroom teachers are increasingly asked to be managers rather than specialists. They are trained not to be “sages on the stage” but “guides on the side,” circulating around the room while their students work on various activities. Baker witnesses this phenomenon on several occasions when he fills in as a classroom aide, and sees the real thing.

Silicon Valley provides the fuel for this contemporary pedagogy. Baker’s school district has issued iPads to each student and uses them as rewards or punishments. Students in good standing use them to complete work on online portals and watch inane videos once they have finished; if they have missed too much work the school blocks their ability to download apps and play games.

Throughout the school day, students of all ages flit from one activity to the next, and teachers constantly fight to keep noise down. The middle school’s technology specialist leads Baker’s students in a group iPad game called “Spaceteam,” which is designed to enhance “team-building” skills, but results in such chaos that teachers down the hall come to shush the class. At the end of a seventh-grade class in which Baker is a student aide, he realizes that “this is what they did four or five or so times a day: snatches of work saved on BrainPOP or IXL or somewhere on the network, papers handed in for grades or signatures or stuffed away…at the same time, small heaps of key terms began to smolder and self-immolate in their minds.” Rather than functioning as a sanctuary from our age’s frantic consumption of media, Baker’s school district has embraced it wholesale, and the results speak for themselves. The students are as distracted in the classroom as they are anywhere else.

Baker notes that “only two things, it seemed, really got the attention of students…the Pledge of Allegiance, and fiction read aloud.” After a morning spent pleading with a class of fifth graders to keep their voices down, Baker is astounded by their transformation when he reads them a Roald Dahl story: “The whole class was motionless.... Carleton’s head was up; Ian’s head was up; Nash’s head was up; the tattletale girls were all intent on hearing every word I was saying. Everyone was listening.” Like all of us, students are drawn to stories, and when class bores them, they tell each other tales about their exploits to pass the time. Noise necessarily ensues. The best teachers Baker comes across know this intuitively, and keep their students focused by teaching through narratives. Students in a high-school history class, for example, are rapt while their teacher improvises stories that explain why and how Hitler and Mussolini rose to power. Baker catches on, and invents a narrative about Gregor Mendel from a series of PowerPoint slides to help a struggling student learn about genetics. Such moments are rare in this book, however, as the Common Core notoriously emphasizes analysis of data over immersion in stories. Using the most human form of communication seems counterintuitive to modern pedagogy.

Baker infrequently editorializes in his book, but English class is one area where the bestselling author cannot remain a bystander. He vents to eighth graders tasked with writing essays on conflicts in stories: “Edgar Allan Poe...write[s] the most terrifying, nerve-wracking story [he] can write. And then later on, generations of high school students have to read through it and find the conflict in it.... I think you should just read the story and find out what happens.” He rolls his eyes at a “taxonomy-of-learning” poster on the wall of a tenth-grade English class: “Activate Prior Knowledge! Identify Text Structure! Monitor Comprehension! It sounded like Spaceteam, the shouting-game app.” The class is working on making a musical playlist for Tim O’Brien’s collection of stories The Things They Carried, a lesson the teacher had downloaded from a generic education website and previously assigned. As Baker chats with students about their projects, it becomes clear that no one has actually read the book.

The students are the bright spot in Baker’s field notes. They laugh and cry, scream for joy and in anger, and show Baker an endless stream of their favorite YouTube videos. Though they exhaust him, he grows to love them, and brings their experience to the fore, lest we forget that they are the central players in the educational drama.

Near the end of the book, Baker hunts down the school nurse to express his concern about a middle-schooler who is taking so much Paxil that he hears voices and cannot sleep. The nurse laments the cultural phenomenon of overprescribing antidepressants: “We just don’t know what to do with our feelings.” Substitute implicitly redirects this criticism at the entire K-12 system. This should not come as a surprise. In a 2011 speech to New York educators, David Coleman, then stumping for the adoption of the Common Core, did not mince words when sharing his opinion on the relevance of narrative writing to a data-driven world: “People really don’t give a [expletive] about what you feel or what you think,” he said. Not long after, informational texts started crowding out fiction in English curricula around the country.

What does an education that has scrubbed itself of beauty and given up on storytelling have to offer in the way of human fulfillment? Not much, Baker seems to suggest. Wonder and curiosity are hard to find in these halls. Fortunately, they are not hard to find in the author. With his fresh set of eyes and attention to detail, Baker reveals the American classroom to be fundamentally broken, held together by the students’ resilience and the teachers’ sheer will. Substitute is an eye-opening indictment of our educational technocracy.

Substitute

Going to School with a Thousand Kids

Nicholson Baker

Blue Rider Press, $30, 736 pp.