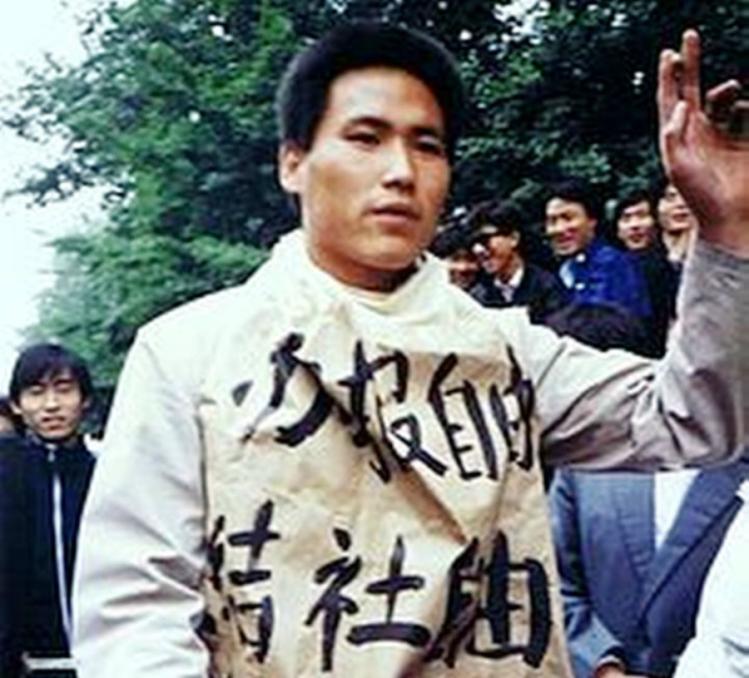

Louisa Lim’s book is not simply a retelling of the Tiananmen story, when those mass demonstrations in Beijing culminated in the massacre of June 4, 1989. Rather it is a look, a quarter of a century later, at some of the effects of what happened, and most particularly at the ways in which the Chinese leadership has sought not so much to cover up the massacre as to erase it entirely from public memory. In this, they have been highly successful. But not completely, and Lim, a former journalist for both National Public Radio and the BBC, has managed to search out some of the survivors of Tiananmen Square who have not forgotten and who no longer fear speaking out.

As she points out, even for us to use the name Tiananmen for what happened back then, and to think of students as the victims, betrays a selectivity that we have chosen as a kind of shorthand for these events. Thus, while students organized and led the demonstrations, it was not they but ordinary Beijing citizens who were the chief victims of the army’s attack. Most of the killing in fact took place in the streets west of the square, particularly at Muxidi some five kilometers away. A Chinese professor once suggested to me that there was little gunfire in the square because most of the troops had exhausted their ammunition by the time they got there.

Moreover, what happened in Beijing was only one part of a widespread national movement that took place in more than sixty other cities. That spring foreign journalists were thick on the ground in Beijing, thanks to the visit of Mikhail Gorbachev in late May. Elsewhere they were not present, and neither were the charismatic (and photogenic) students who led the protests in the capital. Lim in fact gives a whole chapter to the bloody clashes in Chengdu (capital of Sichuan province), which are unknown to most foreigners. (I heard about them simply because four or five days after the massacre, I found myself in the Shanghai airport near a group of Australians on their way home from Chengdu, who were talking of the violence they’d just seen there.)

Though many Chinese obviously remember the events, few are willing to talk to a journalist like Lim. Among these few are the Tiananmen Mothers, a small group of aging women who lost their children in the massacre and seemingly no longer have anything to fear. So too is Bao Tong, a high official at the time whose son, Bao Pu, now in Hong Kong, runs a publishing house devoted, as he says, to filling in the “blank spots” in China’s historical record. Indeed Hong Kong is the one place in China where June 4 decidedly has not been forgotten. Each year on that date tens of thousands of people turn out for a candlelight vigil in a highly impressive display of public memory (I saw it for myself in 2001).

But for most people, particularly those educated since 1989, the massacre simply does not exist. The leadership has had three main responses (or non-responses, if you prefer): oblivion, materialism, and nationalism.

Oblivion, by the attempt to expunge virtually every hint of the event from education and the public record. Even the Shanghai stock exchange was seen as a menace in 2012, when on the massacre’s anniversary it closed down (by accident or design) exactly 64.89 points—numerical shorthand for June 4, 1989—a fact promptly removed from internet sites.

Materialism, because in the last thirty years, more than 600 million Chinese have been lifted out of poverty, a stunning advance unprecedented in human history. Quite rightly that has brought extraordinary gratitude to the leadership. Less fortunate, however, is the increasing scale of corruption and the view that money and expensive possessions are the only true measures of worth.

And finally nationalism, which has meant among other things a revivification of the old slogan “Never Forget National Humiliation” (wuwang guochi). This phrase, which goes back to the early twentieth century, calls on patriotic Chinese to remember that ever since the Opium War (1839–42) foreigners have kept China down, and continue to try to do so today. In a speech this July commemorating the anniversary of the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese war in 1937, President Xi Jinping noted that “no one can change history and facts” (as China often claims the Japanese try to do). But in reality, as Lim shows in this fascinating book, the molding of historical memory may require the ignoring of facts, and Beijing does this very effectively, and by no means only for June 4. China, of course, is hardly unique in suffering from historical amnesia, but most places do not use penal sanctions to enforce forgetfulness.