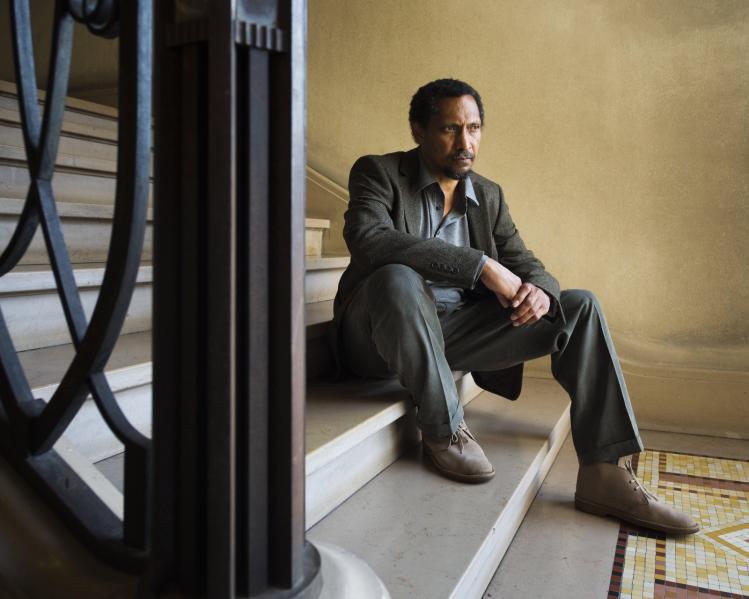

Percival Everett is having a moment. Twenty-three novels into what he would doubtless mock me for calling a “career,” his novels, most of them intellectual thrillers with a heavily satirical edge, or intellectual satires with a bit of thriller thrown in, are attracting the sorts of advances that get headlines in what’s left of the literary press. The Trees (2021) landed on the Booker Prize shortlist. His Erasure (2001) has been made into a movie, American Fiction, which arrives in December, starring one of our greatest living actors, Jeffrey Wright. It’s about as much worldly success as one can imagine accruing in America right now to someone who writes novels as good as Everett’s.

Erasure (Graywolf, $17, 272 pp.) serves as a perfect jumping-on point for those new readers. It concerns Thelonious “Monk” Ellison, an experimental novelist. White critics and editors reject Ellison’s books for not being, somehow, “Black enough,” for Ellison, like Everett, is Black. Ellison at one point offers this definition of the “Blackness” that he is failing to exemplify: “I don’t believe in race. I believe there are people who will shoot me or hang me or cheat me and try to stop me because they do believe in race, because of my brown skin, curly hair, wide nose, and slave ancestors.” Exactly right. Race is a nothing that we make a something, a zero that demands our fealty and our compliance. It is the thing that we have to imagine we see so that all the racism that surrounds us will make sense.

Anyway, Ellison is tired of hearing about the un-Blackness of his novels from his white editors, and he needs money fast. That isn’t really the reason that he starts writing the novel he initially calls My Pafology, a pastiche of Native Son, The Color Purple, and Push. The book is an attempt to insult the readers who think they want something like it. It pours out of him at night, while he drinks and cackles over his own solecisms. His need for money does force him to publish the book, though. Soon, it is a bestseller. Then things get crazier. Everett is such a good writer that even his parodic novel-within-a-novel isn’t really as bad as it needs to be; it’s knit together with a certain grace. This is maybe the only aspect of Erasure that isn’t pitch-perfect.

The publishing industry tends to marginalize a writer like Everett twice. It puts him in a “Black writer” box, and there can only be so many writers in that box at a given moment—I’m not sure why, but that just seems to be how it works. The person in that box has to serve an information-dispensing function for liberal white readers: they must be able to read that writer’s books in order to Get How It Really Is In These Streets, or, failing that, at least they must learn some things about the Psychological Costs of Racism. I am what is called a white person, but I do not know why these white readers want to get these things from novels. We have social scientists for that. I read novels to experience aesthetic bliss, not to learn important lessons. But someone must want all this dreary testifying. Or maybe nobody does; maybe this bias is like the soft-rock radio station that plays in so many workplaces, a station nobody actually chose and nobody actually likes.

It seems to work this way with every other identity grouping, too. You get so many slots. And marginalized genres, too, are rationed: there are not a lot of slots for anybody who gets pigeonholed as heady, experimental, intellectual. We only get to have one goofball experimental writer at a time, and for most of the past two decades it was George Saunders. (Now they’re giving Helen DeWitt a trial run.) This means no serious marketing muscle is used to see whether a novelist like Everett is really too hard, too experimental, for a mass readership. I don’t think he is. I guess we’ll find out when Everett’s James, a retelling of Huck Finn from James’s point of view, comes out next year from a Big Five publisher. Hopefully James will also inspire readers to check out John Keene’s brilliant and somber short story “Rivers” (2015), which uses the same premise. There’s room for more than one author in that box, too.

After I read Erasure I went a little nuts. I read I Am Not Sidney Poitier (Graywolf, $16, 272 pp.), a hilarious picaresque about a young man named Not Sidney Poitier, who finds himself under the guardianship of Ted Turner. After his high-school teacher sexually assaults him, he is forced to run away from home and live through a bunch of adventures that mirror various Poitier movies. He is like Oedipus, who takes so many steps to make sure that he won’t be Oedipus, father-killer, mother-lover. How the stories we refuse to live define us! I read A History of the African-American People (Proposed) by Strom Thurmond, as told to Percival Everett & James Kincaid (Akashic, $15.71, 300 pp.), another metafiction satire, cowritten with James Kincaid, that consists largely of various fake emails written by a made-up congressional intern who thinks that Everett and his friend Kincaid should help the most racist guy in Congress write a history of the people whose history he has, through opposition, done so much to shape. It is one of the great sick jokes in the American literary canon. And yet, notice how Everett can use the same metafictional gamesmanship to tell a far more moving story. That’s Percival Everett by Virgil Russell (Graywolf, $15, 240 pp.), in which Everett’s dying father writes a novel about his son, or the reverse. It seems like what a novelist would write in tribute to his actual father, though I wouldn’t want to presume.

Speaking of family life, I have for the past two years taught Everett’s So Much Blue (Graywolf, $17, 256 pp.) to students in a class on the idea of the writing process. It is the story of a painter who is at a crisis moment in the life of his family. Events force him to remember the harrowing weeks he spent in El Salvador during that country’s civil war. The other night, when we were discussing it, a student tried to answer the question of whether the protagonist loves or hates his wife, whom he holds at arm’s length for much of the novel. “I can’t just say anything simple about it,” the student said, and laughed uncomfortably. “That’s because it’s a good novel, and because you’re a good reader,” I said.

Can you believe they pay me to have conversations like that, with smart kids like her? What luck. But even my job is not as good as the job that the hero of Everett’s Dr. No (Graywolf, $16, 232 pp.) has. He is one of the world’s leading experts on the concept of nothing, and since nothing, as such, plays a large role in the plans of John Sill, a would-be supervillain, our hero is forced onto Sill’s team as a Nothing consultant. It’s a dizzying and funny caper from a writer who some people would hate sight unseen, who has never gotten the hype he deserves, and who readers of all backgrounds have not been sufficiently invited to enjoy. Because of nothing.