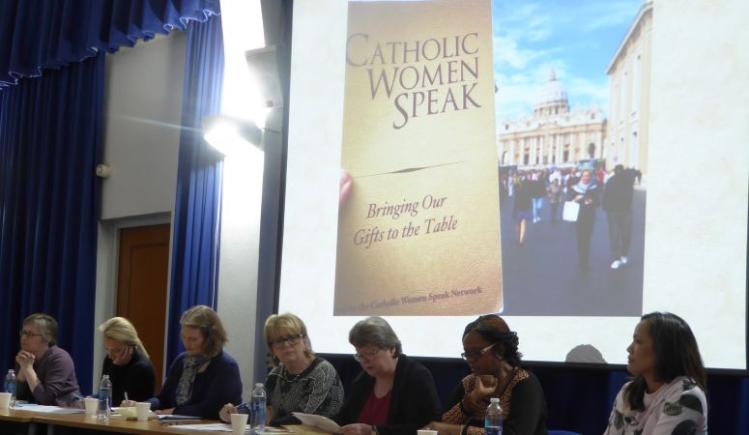

When cardinals and bishops entered the Vatican meeting hall for the Synod on the Family in October 2015, they walked past a table inviting them to take a free copy of the book, Catholic Women Speak: Bringing Our Gifts to the Table. The book was edited by the Catholic Women Speak Network and published by Paulist Press. Three hundred books were delivered to the hall, and they were nearly all taken.

That felt like the miraculous culmination of an odyssey that began on a wet British Sunday afternoon in December 2014, when I impetuously started a Facebook group called “Catholic Women Speak.” That would be the beginning of an ongoing adventure in faith that would bear fruits beyond my wildest imaginings, culminating (so far) in the synod book. Further projects are in the pipeline.

I started the group because, like many others, I was beginning to realize that tackling the issue of the role of women in the church was not one of Pope Francis’s priorities, however much he acknowledged the problem. The initial euphoria of his election was gradually being replaced by the realization that we women would continue to be joked about, patronized, and romanticized, but the chances of our being treated as full and equal members of Christ’s church seemed as remote as ever. I wondered if there were others who felt the need for a place where we could share the challenges we face as we seek to sustain a vibrant and hopeful faith amid the often conflicting demands of the institutional church and secular society. With that in mind, I made it a closed group, with membership restricted to those who identify as Catholic women.

The group grew quickly, and today it has nearly fifteen hundred members. We get occasional requests to join from men in blonde wigs and Barbie dolls in bikinis, as well as several from Pope Francis, but the moderators have become adept at spotting imposters. It is a lively forum where women discuss issues ranging from biblical interpretation, social and political commentary, church teachings and their impact on women’s lives, the quality of the Sunday homily, and women’s ordination, to natural family planning, contraception, gender, and sexuality. In our discussions we resist being limited to any single issue, for we have a collective commitment to ensuring that our dialogues reflect the diversity and complexity of women’s lives in the worldwide church. Our debates are sometimes robust and occasionally have to be moderated when they become overheated, but on the whole they are theologically literate, personally engaged, and respectful. Membership is drawn from the global church, though most of those engaging regularly are in Britain and the United States. Some have left because they regard the group as lacking in obedience to church authorities, but many say that it has revitalized their faith. One woman recently posted that she has started going to Mass again, as a result of her involvement with the group. That Facebook community forms a crucial part of this story.

In late April 2015, I went to see somebody I know in the Pontifical Council for Culture to ask how women might be given a greater presence in the October Synod on the Family. He jokingly said that we should have published a book, because that seemed to be how different interest groups attracted the attention of the media and gained publicity for their cause. I left his office knowing that it was, practically speaking, impossible to publish a book in time for the synod, but I had a jingle singing in my soul: “With God all things are possible.” I had met Fr. Mark-David Janus, president of Paulist Press, in Rome the year before. Serendipitously (I always think “serendipity” is another word for “miracle”), I had kept his visiting card and even remembered which drawer I had shoved it into. I emailed him late at night on May 4 and asked if Paulist Press would be willing to publish a book in time for the synod, and what kind of deadlines we would have to work to. He responded immediately and positively. That began one of the most intense and exciting projects of my life.

The suggestion was for me to put together a very short book—about ten thousand words—with a few well-known contributors, to be delivered by the end of June. I decided we could be more ambitious than that. I sent out an appeal to the Facebook group and emailed Catholic women theologians working in the areas of feminism, gender, and moral theology. My vision was to put together a book of short, accessible essays weaving together academic theological perspectives and personal narratives, and ensuring the widest possible representation of Catholic women’s voices.

I wanted the book to be a collaborative endeavor, so we formed an editorial team through the Facebook group. I took on responsibility for the overall editing and structure of the book; Diana Culbertson, OP, agreed to act as co-editor; and essays were circulated to a wider group for review, translation, and proofreading.

The three criteria for inclusion were that contributors should be practicing Catholics, they should be writing on issues relevant to the synod, and they should offer perspectives that revealed some of the struggles women face in seeking to be faithful to church teaching while living in accordance with their consciences. We agreed that the tone should be irenic, inviting dialogue and engagement, and we set ourselves a goal to give a copy of the book to everybody attending the synod. The book was written primarily with that ecclesiastical readership in mind.

We delivered a forty-five thousand word manuscript with forty-four contributors from sixteen different countries to the publishers at the beginning of July. Contributions included reflections on Scripture, history, and theology; on marriage and family life, divorce and remarriage, and same-sex love; on motherhood, sexuality, and birth control; on celibacy and the single life; on poverty, migration, and violence; and on women in church institutions and structures. Many of the contributions were original, but there were also several previously published pieces. Contributors included some of the best known Catholic women theologians from around the world (Agnes Brazal, Lisa Sowle Cahill, Margaret Farley, Nontando Hadebe, Elizabeth Johnson, Ursula King, Cettina Militello, Jean Porter, Janet Martin Soskice, and others), as well as women telling their sometimes heart-breaking personal stories of faith and failure, healing and hope. Because we were committed to making the essays short and easy to read (hoping that some cardinals and bishops might read them during their coffee breaks at the synod!), we had to whittle down a number of substantial academic essays to a fraction of their original length. It was a remarkable experience of cooperation and indeed of scholarly humility, because not a single theologian protested when we reduced her finely honed and nuanced piece to the bare bones of an argument, with a reference to the full piece for those who wanted to read more.

Behind the scenes, Cardinal Gianfranco Ravasi of the Pontifical Council for Culture was quietly supportive of the project. He sent us a letter of support that he agreed we could quote from in the book’s Introduction. Former Jesuit Provincial of East Africa and Principal of Hekima University College in Nairobi, Orobator Agbonkhianmeghe, agreed to write the Foreword.

In the meantime, the project had begun to experience the Topsy effect—it was growing and growing. Negotiations to have the book distributed to synod participants were proving difficult and time-consuming, with every avenue of enquiry turning out to be a dead end. However, we decided to organize a launch event in Rome in the week prior to the opening of the synod, to publicize the book and raise awareness of women’s presence in the church. An appeal to foundations and religious orders resulted in our having sufficient funds to plan a major event bringing together contributors from around the world. By now, the jingle in my soul had changed from everything being possible with God, to walking on water. I began to understand how Peter must have felt when he clambered over the side of the boat and suddenly thought, “What am I doing?!” I kept telling myself, “Don’t waver, keep eye contact with Jesus, and believe this is possible.”

Earlier in the year, I had attended an excellent event on women in the church at the Pontifical University Antonianum in Rome, organized by the Rector Sister Mary Melone and the Chilean ambassador to the Holy See, Monica Jiménez de la Jara. I asked Sister Mary if she would allow us to use the Antonianum for our launch. She responded enthusiastically and offered us gracious and continuing support throughout our time in Rome, as did Ambassador de la Jara and the British ambassador to the Holy See, Nigel Baker. Twenty contributors agreed to take part from Argentina, Chile, Italy, Germany, Ireland, South Africa, the Philippines, Nigeria, the United States, Canada, and Britain. I found myself making travel arrangements, booking accommodation, and putting upon the hard-working finance administrators at the University of Roehampton, where I work, to manage the budget. They kept reminding me that I should have gone through several form-filling exercises and procedures before embarking on such a project, but it was good to discover that even in the tightly controlled bureaucracies of modern academia, one can still sometimes find creative gaps in the system. Besides, one of my favorite sayings in such situations is that it’s easier to get forgiveness than permission. We wanted the launch to be an occasion of celebration, so we decided to end with a performance of music and dance and a reception.

WE GATHERED IN ROME on September 30 for a party at the flat of Kate and Josh McElwee, the National Catholic Reporter’s Rome correspondent, where we gift-wrapped a number of the books. The event on October 1 began with a joyful Mass, celebrated by Argentinian priest Fr. Augusto Zampini, with much singing and dancing and thanksgiving. There was only one remaining problem. We had not yet managed to find a way to distribute our books at the synod. The publishers had airfreighted three hundred copies hot off the presses to a convent in Rome for collection, and some members of the Network had already given copies to priests, bishops, and cardinals they knew, but giving it to every synod participant was beginning to seem like one ambition too many.

The McElwees agreed to store the books in their flat while we negotiated with the synod organizers. My long-suffering husband made several taxi trips across Rome with boxes of books as we followed up various leads, only to find they were not leading anywhere. Finally, as we gathered in the Antonianum auditorium to begin the launch with an afternoon of panel discussions, we received a message that the final answer was no. We would not be allowed to distribute our books to the synod Fathers because they already had too much to read.

My head told me to give up, but my heart told me to keep trusting. An hour after receiving that message, and with much behind-the-scenes activity, we were given the telephone number of a contact at the Vatican publishing house, Libreria Editrice Vaticana. They offered us a table in the Synod Hall on which to display and distribute our books—a solution beyond anything we would have dared to ask for.

As we had hoped, the book received widespread media coverage and many positive reviews. The enthusiasm continues unabated. We have had launches in New York, Johannesburg, and London as well as Rome, a number of groups are using the book as a study resource, and we are planning a follow-up publication. The book is already on its fifth reprint.

Nevertheless, none of this was enough to solicit a response from the hierarchy. We sent out invitations to a number of cardinals and archbishops to attend the launch, but only received three acknowledgements and no acceptances. We asked if Pope Francis would send us a message of welcome, but again we received no response. It is hard not to conclude that the men who rule the church are willing to listen only to women whom they themselves select, and who are guaranteed to tell them only what they want to hear.

The synod itself gave women little reason to hope for change in the areas that most affect women’s lives. Canadian Archbishop Paul-Andre Durocher was a lone voice when he drew attention to the need for greater inclusion of women in decision-making positions in the church, including the possibility of female deacons. The few women auditors—thirty in all—were not allowed to vote. The question of women’s roles and responsibilities in the context of family life and church institutions had a lower priority than many other issues, such as divorce and remarriage and same-sex relationships. Important though these are, the centrality of women’s roles in families and in the care of children, the exodus of women from the church, the marginalization of women in church institutions and structures, and the disproportionate effects of poverty, migration, and violence on women’s lives should have made women the most important topic of discussion at the synod—with their full and equal participation. Lucetta Scaraffia, editor of the “Women, Church, World” monthly supplement in L’Osservatore Romano and a contributor to our book, wrote a scathing account of her experience as one of the women auditors in the French newspaper Le Monde. She describes the inability of the assembled prelates to recognize women as their equals, and she speaks of being ignored and belittled by her clerical counterparts.

Yet if the synod gave little scope for optimism, recent developments suggest there may be a movement for change that is gradually gaining ground. I dare to hope that Pope Francis might be working quietly behind the scenes, aware perhaps that improving the position of women in the church remains the most neuralgic of tasks in light of the deep-rooted misogyny that still infects some of his clerical counterparts, and the cowardice that prevents others from speaking out. He has officially decreed that women are to be included in the foot-washing ceremony at the Holy Thursday liturgy. While many parishes already do this, it will now be the norm. An article in the semi-official Vatican newspaper L’Osservatore Romano, advocating that members of the laity, including women, might preach the homily during Mass has caused widespread debate and much celebration among Catholic women’s groups. Yet these remain piecemeal gestures. Sooner or later, church authorities are going to have to accept the need for free, informed, and inclusive theological reflection about all these issues, including contraception and women’s ordination, if the sensus fidelium is to have any meaning at all.

The experience of the past year has been a profound affirmation of my Catholic faith, not because of, but in spite of, the institutional church. The Holy Spirit is more powerful and more subtle than all the bumblings of the institution with its androcentric and anachronistic hierarchies and its appalling abuses of power, including the ongoing scandal of sexual-abuse cover-ups. Our book might be nothing more than a smoldering wick in the embers of the synod. We women might often feel that we are the bruised reeds struggling to grow in the marshy margins of the visible church. Yet we place our hope in the Christ who fulfils the words of the prophet: “A bruised reed he will not break, and a smoldering wick he will not snuff out, till he has brought justice through to victory” (Matthew 12:20).

Whatever obstacles and injustices we encounter, we must continue to work prayerfully, trustingly, collaboratively, and hopefully in order to become the change we wish to see, and we must make music and dance in the midst of our struggles and disappointments. Sometimes, we must also be willing to rage and overturn the tables in the temples of power—though I’m glad to say that, as far as I know, nobody overturned our book table in the synod hall.