Although great progress has been made in the past fifty years in Catholic-Jewish relations, there remains an underlying fragility. Not surprisingly, reflexes that developed over centuries of estrangement do not disappear after a few decades. Two distinct but interrelated Italian controversies demonstrate this.

Tensions flared when the Italian Biblical Association (ABI) publicized two conferences to be held this coming September. The title of the first was announced as “Israel, People of a Jealous God: Consistencies and Ambiguities of an Elitist Religion.” The conference description noted that today “there is a return to religion with absolutist and intolerant accents.” Consequently, the conference would explore how the God of Israel developed “from a subordinate divinity [to gradually become] the exclusive deity of a people who, in an elitist manner, believe[d] themselves to be his unique possession,” and hence superior to other people. Evidently, the conference organizers were interested in how fundamentalism arises in all three Abrahamic traditions. Unfortunately, their phrasing echoed a long-lived polemic that contrasted an enlightened Christian universalism with a narrow Jewish particularism. The most prominent critic was Rabbi Giuseppe Laras, the former chief rabbi of Milan and president emeritus of the Italian Rabbinical Assembly. A letter of protest was sent, not to the officers of the ABI, but to various Vatican officials and personnel and to the Italian Bishops’ Conference. The letter lamented a persistent “undercurrent of resentment, intolerance, and annoyance on the Christian side toward Judaism.” It accused the ABI of promoting the attitude that regards Jews as “execrable, expendable, and sacrificeable” and encourages a “resumption of the old polarization between the morality and theology of the Hebrew Bible and of Pharisaism, and Jesus of Nazareth and the Gospels.”

The letter also blamed Pope Francis for encouraging a revival of Marcionism (the ancient heresy in which the “jealous God” of the Old Testament is contrasted with the loving God of the New). After acknowledging that post–Vatican II church statements have repudiated such invidious comparisons, the letter continued: “What a shame that they should be contradicted on a daily basis by the homilies of the pontiff.... One need think only of the law of ‘an eye for an eye’ recently evoked by the pope carelessly and mistakenly...[recalling] anti-Judaism on the Christian side.”

Reactions quickly appeared from various quarters. The president of the ABI, Professor Don Luca Mazzinghi, denied Laras’s accusations. “The idea that the God of the Hebrew Bible is different in some way from the God of the New Testament is absurd and offensive,” he said. “It is even more the case for us who study and work on the two Testaments that the God whom Jesus called ‘Father’ is the same as the God of Israel, the people God has chosen and whom Jesus is part of.” He forcefully declared, “Any shadow of anti-Semitism, which we repudiate in the strongest terms, has always been absent from our Association.”

Announcing that the description of the ABI conference had been revised to stress that the relevant topics applied to Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, Mazzinghi also noted that the conference title had been changed to “People of a ‘Jealous God’ (cf. Exodus 34:14): Consistencies and Ambivalences of the Religion of Ancient Israel.” He expressed confidence that ongoing dialogue would overcome allegations from critics that had lost “all sense of proportion.”

Indeed, that seems a likely outcome as conversations continue among the Jewish community, the Italian Bishops’ Conference, and the ABI.

Bringing some of the pope’s homilies into the dispute, however, provided an occasion for some within the Catholic community to discredit him. A Matthew Schmitz essay in First Things (“Rabbi Objects to Pope Francis’s Anti-Jewish Rhetoric”) accused Pope Francis of “anti-Jewish rhetoric,” saying that “too many authoritative Christian voices—both bishops and theologians” have excused it for too long. The Catholic World Report ran an article by Peter M. J. Stravinkas, asking if Francis was guilty of “Papal Anti-Judaism?” It opined that the pope has said “over and over again that he is no theologian and that he doesn’t care much for theology...that [is the] attitude which has caused so much damage in this pontificate.”

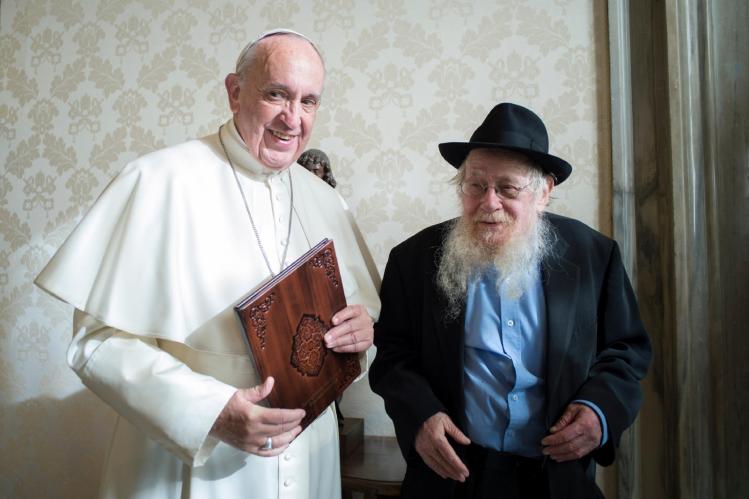

Since the pontiff is widely known for his close friendships with Jews in his native Argentina, and even co-wrote a book with Rabbi Abraham Skorka on their dialogues over the years, what was the basis of Rabbi Laras’s critique of the pope?

Depending on the daily lectionary readings, Pope Francis does have a habit of uncritically repeating Gospel polemics against various Jewish leaders in Jesus’ day. This most often happens in the daily homilies he delivers in Domus Santa Marta in the Vatican. In a recent reflection, for example, he spoke of the Temple high priests as manifesting “arrogance and tyranny toward the people” by manipulating the law:

But a law that they have remade many times: so many times, to the point that they had arrived at 500 [sic] commandments. Everything was regulated, everything! A law scientifically constructed, because this people was wise, they understood well. They made all these nuances, no? But it was a law without memory: they had forgotten the First Commandment, which God had given to our father Abraham: “Walk in my presence and be blameless.” They did not walk: they always stopped in their own convictions. They were not blameless!

A listener or reader could readily be excused for wondering if the pope saw Judaism in the time of Jesus as heartlessly legalistic because of its focus on the Torah. Might that hold true for Jewish spirituality today as well?

Similarly, when preaching on the woman caught in adultery in John’s Gospel, Francis remarked about the Pharisees: “they thought they were pure because they observed the law...but they did not know mercy.... The description used by Jesus for them is hypocrites: they had double standards.”

Rabbi Laras was correct in asserting that postconciliar documents issued by the Commission for Religious Relations with the Jews caution against such use of Gospel polemics. Its 1985 instruction on how to present Jews in preaching and education, for instance, noted that “The Gospels are the outcome of long and complicated editorial work.... [S]ome references hostile or less than favorable to the Jews have their historical context in conflicts between the nascent church and the Jewish community. Certain controversies reflect Christian-Jewish relations long after the time of Jesus.” In particular, the commission stressed that the Pharisees—widely understood to have been the precursors of rabbinic Judaism—shared with Jesus many defining convictions: “the resurrection of the body; forms of piety, like almsgiving, prayer, fasting (Matthew 6:1–18) and the liturgical practice of addressing God as Father; [and] the priority of the commandment to love God and our neighbor (Mark 12:28–34).”

Does this mean that Pope Francis harbors “anti-Jewish” attitudes? To answer that question we need to understand the pope’s homiletic purpose in using polemical Gospel texts in this way. In no case does he criticize either Judaism as a religious tradition or Jews today. Rather, he invites Christians to examine their own consciences. In particular, he deploys the harsh and sweeping rhetoric of the New Testament against clericalism among Catholic priests and hierarchy. It is his fellow priests and bishops, not Jews, that he has in mind. In the homily cited above about the high priests, Francis went on to criticize “that spirit of clericalism,” found in the church today. “Clerics feel they are superior, they are far from the people; they have no time to hear the poor, the suffering, prisoners, the sick.... The evil of clericalism is a very ugly thing!... Today, too, Jesus says to all of us, and even to those who are seduced by clericalism: ‘The sinners and the prostitutes will go before you into the Kingdom of Heaven.’”

It is regrettable that Pope Francis does not occasionally mention the affinity between Jesus and his Pharisaic contemporaries or simply attribute to only some of the scribes or Pharisees the human temptation to sanctimoniousness or arrogance. Without such caveats, he risks unintentionally reinforcing Christian caricatures of Judaism. However, this blind spot hardly amounts to “anti-Judaism,” particularly when he has elsewhere spoken eloquently and consistently about his love for the Jewish people and traditions.

On the subject of Judaism’s Torah-centered spirituality, in February Francis greeted “Rabbi Abraham Skorka, brother and friend” on the occasion of being presented with a limited edition publication of a new illuminated volume of the Torah. “[We are] together today around the Torah as the Lord’s gift, his revelation, his word,” Francis said. “The Torah, which Saint John Paul II called ‘the living teaching of the living God,’ manifests the paternal and visceral love of God, a love shown in words and concrete gestures, a love that becomes covenant.”

Although expressed in everyday speech, Francis also offered some profound reflections on the Torah to the International Council of Christians and Jews in 2015:

The Christian confessions find their unity in Christ; Judaism finds its unity in the Torah. Christians believe that Jesus Christ is the Word of God made flesh in the world; for Jews the Word of God is present above all in the Torah. Both faith traditions find their foundation in the One God, the God of the Covenant, who reveals himself through his Word. In seeking a right attitude towards God, Christians turn to Christ as the fount of new life, and Jews to the teaching of the Torah. This pattern of theological reflection on the relationship between Judaism and Christianity arises precisely from Nostra aetate (cf. no. 4), and upon this solid basis can be and must be developed yet further.

The pontiff sees that since the Second Vatican Council, Jews and Catholics have undertaken a “journey of friendship,” which is why he wrote in Evangelii gaudium:

Dialogue and friendship with the children of Israel are part of the life of Jesus’ disciples. … God continues to work among the people of the Old Covenant and to bring forth treasures of wisdom which flow from their encounter with his word. For this reason, the church also is enriched when she receives the values of Judaism. While it is true that certain Christian beliefs are unacceptable to Judaism, and that the church cannot refrain from proclaiming Jesus as Lord and Messiah, there exists as well a rich complementarity which allows us to read the texts of the Hebrew Scriptures together and to help one another to mine the riches of God’s word.

In fact, during his 2015 visit to Philadelphia, Francis stopped briefly with his friend Rabbi Skorka to view an original sculpture by artist Joshua Koffman depicting exactly this concept. Synagoga and Ecclesia in Our Time, commissioned by Saint Joseph’s University to mark the golden jubilee of the conciliar declaration Nostra aetate, reverses medieval portrayals in which the feminine figure of the church triumphs over the defeated feminine figure of the synagogue. Francis blessed the new artwork in which two sisters of equal dignity enjoy studying their sacred texts together.

Francis’s awareness of the long history of Christian oppression of Jews was also clearly evident when he wrote:

I too have cultivated many friendships through the years with my Jewish brothers in Argentina and often while in prayer, as my mind turned to the terrible experience of the Shoah, I looked to God. What I can tell you, with Saint Paul, is that God has never neglected his faithfulness to the covenant...and that, through the awful trials of these last centuries, the Jews have preserved their faith in God. And for this, we, the church and the whole human family, can never be sufficiently grateful to them.

There is an added poignancy to a pope expressing gratitude to Jews for remaining faithful to their covenantal life with God when one realizes that it was Christians who were oppressing them over “the last centuries.”

It is clear that Pope Francis has great personal reverence for the Jewish people and tradition, for the Torah, and for the “journey of friendship” that Jews and Catholics have undertaken for more than fifty years. It is unfounded and unfair to accuse him of being “anti-Jewish” on the basis of a handful of ill-chosen comments intended as criticism of his own church. This kind of reproach seems grounded less in a concern for Catholic-Jewish relations than in broader critiques of Francis’s theology and style.

Seen more broadly, these recent incidents demonstrate the constant, conscious effort that is needed to overcome the legacy of the painful past between Jews and Christians.