This essay is the third in a series of Lenten reflections on world cinema and social justice. Throughout Lent, Nicole-Ann Lobo will choose a different classic film, using it as a point of departure for a meditation on race, spirituality, and social change. Catch up on her first and second pieces, and check back soon for the next installment.

The opening scene of Aldo Francia’s Ya No Basta Con Rezar (1972) features trams moving down the hilly coast of Valparaíso, the city’s colorful buildings in view and rhythmic chants on the soundtrack. The film, whose title translates to “It is no longer enough to pray,” is set during the Eduardo Frei Montalva presidency in mid-1960s Chile and includes many mesmerizing shots of the coastal city and its natural beauty. But it’s hardly an ode to its remarkable setting. Instead, it’s an indictment of a society’s gross inequality.

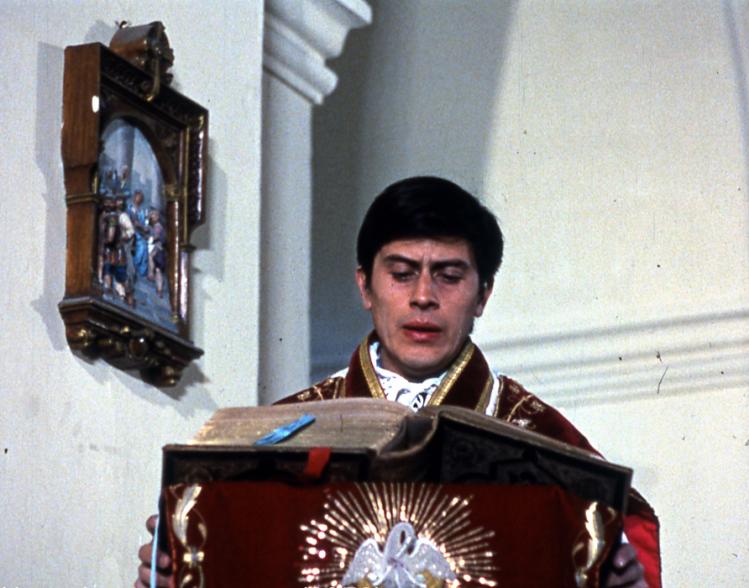

Ya No Basta Con Rezar follows Father Jaime—a young priest played by Chilean actor Marcelo Romo—as he awakens to the poverty and inequality gripping Valparaíso. Initially, he works with the more conservative Father Justo in a parish serving a bourgeois community. The parishioners give alms and attempt to organize events for the poor, but their lives are marked by excess: ornate jewelry, stylish clothing, lavish parties. One of the richest of Jaime’s parishioners owns a shipyard (the film later follows its workers as they go on strike).

Jaime’s anguish builds upon realizing the need to side with the poor. As workers are about to stage a protest in the hills, Jaime reads a passage from Matthew 23 in his bedroom: “Woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites!” it begins, Jesus’s exhortation on the insufficiency of Pharisaical piety in the absence of mercy, justice, and faithfulness. At the protest, Jaime runs through the unfolding chaos and picks up the body of a wounded man; moments later, we see him at a luxurious dinner, clearly unsettled by the surroundings and the jarring laughter of his upper-class parishioners, who drink from crystal stemware, and eat from plates overflowing with food.

His displeasure continues to grow in proportion to his counterpart’s apathy. At one point Jaime asks Justo why a typhus epidemic is only affecting the poor neighborhoods, but the unconcerned pastor simply replies: “If we were to ask ourselves about each of the designs of the Lord…!” Soon Jaime realizes the insufficiency of small actions in the face of such structural obstacles. The wealthy parishioners may have given to the poor, but it’s the continued oppression of the poor that enables the wealthy to lead such opulent lifestyles in the first place. With this realization, Jaime’s political inclinations are unleashed.

The influence of Italian Neorealism in the film is evident in the shakiness of many shots, as Francia incorporates verité footage of protests and demonstrations taking place in Chile alongside the film’s unfolding narrative. With his sympathies toward the poor now plainly evident, Jaime faces pushback from governmental authorities and the Church hierarchy. In one decisive moment, as Justo tells him that the minimum obligation the poor have is to climb the hills to get to Mass, Jaime realizes he has had enough. “We are not so sure where the house of God is,” he replies, and decides to build a church outside the wealthy precincts of Valparaíso—a parish for the poor.

At the film’s conclusion, as bourgeois civilians hold a procession on a flotilla of boats, Jaime leads workers in a march toward the city center, their revolution in motion. They are met there by armed guards, who open fire. In what has become an iconic moment, Jaime throws a rock—the manifestation of his political awakening. Today, in Santiago, graphic images of this scene can be found plastered on street corners, sold in gift shops, graffitied on park walls. It marks a far cry from the film’s initial reception following its 1973 public release, which was a watershed year in Chilean politics: the overthrow of democratically elected president Salvador Allende and the beginning of Augusto Pinochet’s seventeen-year military rule. Francia had worked as a pediatrician in Chile before seeing Vittorio de Sica’s Bicycle Thieves, which prompted him to pursue a career in filmmaking. He vowed to never again make a film after the 1973 coup.

In the period the film is set in, the conservative Christian Democratic Party (which drew inspiration from the French Catholic philosopher, Jacques Maritain) had a stronghold on Chile’s politics. The institutional church in Chile was known for its support of more conservative state policies. Not only was it vocally opposed to the social progressivism that came out of CELAM (the Latin American Episcopal Council that met in 1968 and urged bishops to consider a preferential option for the poor), but certain segments supported the Pinochet coup.

The film extols the idea of the new worker-priest, rooted in the progressive Catholic tradition (particularly in Latin America.) A real-life example might be Camilo Torres Restrepo, who helped co-found the Sociology Faculty at the National University of Colombia. He was involved in various student and political movements, and when pressured by the Church to dissociate from these groups, he abandoned his academic position and became a guerrilla fighter, twelve years before Ya No Basta Con Rezar’s release. Torres is remembered for this quote: “If Jesus were alive today, He would be a guerrillero.”

Liberation theology, which deems prayer insufficient without also taking action to lift up the marginalized, informs Ya No Basta Con Rezar throughout. Some of the critics of liberation theology have charged it with inciting violent revolution. Indeed, the final rock-throwing scene could be viewed as such an act. But the scene also illustrates to me the theological imperative for revolution set forth by the Dominican priest Herbert McCabe, who suggested that the most likely model for the Christian minister is the revolutionary leader. “We may say that Christianity is Marxism carried a great deal further,” he wrote in Priesthood and Revolution.

The film left me with many questions. While contemplating its message, I began reading online comment forums, where the debate over Ya No Basta Con Rezar still rages. Viewers either deem the movie unforgivably political and disgustingly propagandistic, or hail it as a prophetic vision for the church. But both feel excessive: can violence ever factor into the pursuit of social justice? Of course, the Church tells us that violence is never an option. But more pressingly, I remain haunted by the title question: is praying ever really enough?

These sorts of concerns have been on my mind this Lenten season, when in the face of what seems continuously unfolding catastrophe, praying often feels futile. The stock offer of “thoughts and prayers” has long since become hollow, even insulting. Living in a city like New York, where the injustices of an exclusionary socioeconomic system are visible on every corner, it feels that prayer alone won’t help in enacting any tangible change.

McCabe found that sometimes, a class-structured society’s violence is so pervasive and reaches such intensity that “it can only be contained by revolutionary violence.” But this, he admits, is “an exceptional and regrettable measure; for the dominative society, institutionalized violence is the very condition of its existence.” Indeed, violence, more than other displays of excess, can be counterproductive. We must then accept our humility in small, if sometimes unsatisfying incremental actions toward change. Perhaps that’s what the prayer attributed to Romero, “Prophets of a Future Not Our Own,” means. “We are workers, not master builders…” it goes, and this realization contains a sense of liberation. Rather than doing everything, we are empowered “to do something, and to do it very well.”

By embracing both our smallness and our commitment to the social gospel, we can make a difference in other ways. As Pope Francis said in a homily last year, we can base our very real, temporal actions in hearts completely rooted in prayer. For as McCabe attests, the Christian revolution embodies a spirit that transcends, but is not apathetic toward, temporal concern. Unlike Marx, Jesus was concerned not just with the limitations of an unjust life, but also with the emptiness to be found in a spiritually desolate death.