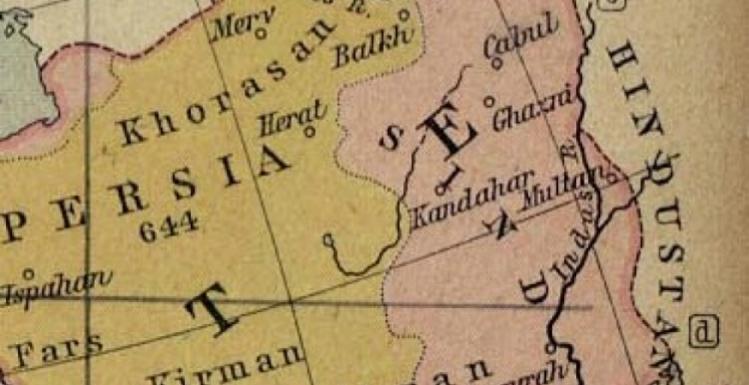

Back in rather less fraught days in the Middle East—1994 to be precise—William Dalrymple journeyed from Athos to Egypt in the footsteps of the sixth-century monk John Moschos. The account of his travels, From the Holy Mountain, is one of the most accessible guides to the ancient Christian communities of that region. Dalrymple lives for much of the year at his farm outside Delhi, and his subsequent books have described the history and the culture of the subcontinent. On the dust jacket of Return of a King: The Battle for Afghanistan, 1839–42 (Vintage, $17.95, 560 pp.), his publicist has quoted a puff by Salman Rushdie: “a scholar of history who can really write.” Perhaps more telling, to a historian’s command of many sources in a variety of languages Dalrymple adds a journalist’s ability to pick out the seemingly incidental detail that brings a story to life. In this instance it’s the story of Britain’s first invasion of Afghanistan. That happened in 1839, and it wasn’t Britain but the (British) East India Company—technically a private enterprise—that ran a good deal of what would eventually become an empire. Like General Motors and the United States, however, what was good for the East India Company was judged to be good for the United Kingdom, and national troops were practically indistinguishable from the company’s. It was the beginning of the “Great Game,” an undeclared war between Britain and Russia for control of central Asia. The invasion was a complete disaster. After some success, the British army was entirely destroyed as the Afghanis united under the banner of the Prophet. Had this somewhat overlong but nevertheless enthralling book been available to NATO’s generals and their political masters before the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan, they might well have had second thoughts.

Full disclosure: I know Peter Brown, the author of Through the Eye of a Needle: Wealth, the Fall of Rome, and the Making of Christianity in the West, 350–550 AD (Princeton, $24.95, 792 pp.). (I also know Dalrymple, albeit only very slightly: we were filmed by the BBC discussing saints in the crypt of England’s only pre-Reformation Catholic church, while being wined and dined courtesy of a neighboring hostelry.) For six of my nine undergraduate terms at Oxford, Brown (now a professor at Princeton) was my tutor, and we had subsequent dealings, now long ago. But I make no apology for recommending his latest volume. Books such as The Cult of the Saints, The Body and Society, and, of course, Augustine of Hippo have fundamentally changed the way we think about Christianity from 400 to 800 AD. His new book will do likewise, but it is particularly important because of its relevance to two debates within the church: one about wealth and how to handle it, and the other about clerical celibacy. The celibacy of the priesthood, Brown argues, was not imposed from on high. Instead it came from below, insisted on by the laity who were handing over their riches for sacred purposes. This is so formidable a tome—530 pages of text, another hundred or so of notes—that many will assume it is for scholars alone. That would be a mistake. It is for all, as one reviewer put it, who want to understand a culture that has had such a lasting impact on our own. And, I would add, it is for all those who throw about the phrase “the Constantinian Church” as a term of abuse. As both Dalrymple and Brown demonstrate, there is a great deal to be learned from history, but you have to read it with care.

Eve Harris’s The Marrying of Chani Kaufmann (Grove Press, Black Cat, $16, 384 pp.) was a first. I had never before read a novel because of a recommendation in a homily, nor had I read one that explored tensions within the Orthodox Jewish community. The priest suggested the book because it is partly set in the area of London that my parish serves, and also because the priest said it was funny. There were indeed laughs to be had, especially in the earlier pages, but the novel became darker as the story unfolded. Chani is a feisty young lady from a poor family whose much-loved but remote father is a rabbi, her mother much put-upon. She is determined to marry for love. Baruch is a rather wimpish young man with a boorish mother trammeled by concerns of status and a wealthy businessman father who is more sympathetic. Baruch, too, wishes to marry for love. Chani is that love, which is unfortunate because the feeling is not reciprocated. Not that, within the community, Chani’s feeling greatly matter. Despite the best efforts of Baruch’s mother, the marriage goes ahead, and though it all but ends in disaster on the wedding night, Baruch and Chani face the future with hope. That cannot be said of all the characters populating Harris’s book. For one rabbi’s wife, the strains of living the life of an Orthodox Jew prove too much: she walks out. The detailed description of that life and its rituals forms the narrative’s particular fascination. Harris has taught in Israel, but she drew most of her inspiration from teaching in an all-girls (naturally), ultra-Orthodox Jewish school in London. She now teaches in an all-girls Catholic convent school, also in London. I think I can guess which one and await with trepidation The Marrying of Brigid Flanagan.

See what other Christmas Critics are reading here.